June 8, 2022

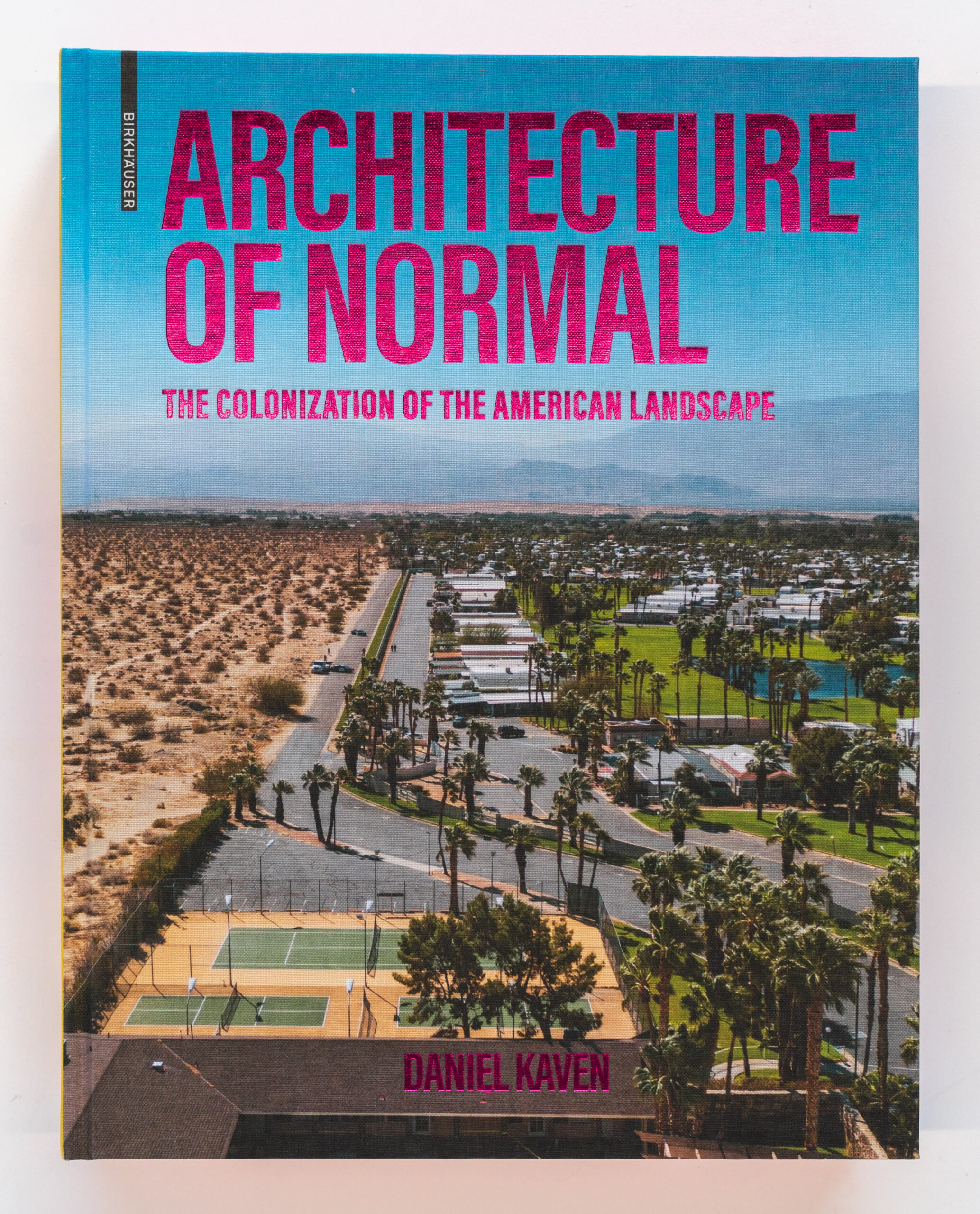

On the Road or In the Air, Daniel Kaven Sees the Journey as Destination

You began sharing excerpts from Architecture of Normal on Instagram a few years ago, while you were still writing. Did you know from the beginning the story you wanted to tell?

When I started this project, it was actually a bit amorphous and a bit of soul-searching, a kind of vision quest, that coordinated with my 40th birthday.

How did you get the balance right between a personal journey and a historical explanation?

That’s something I’ve thought a ton about over the years. The most compelling documentaries or books, I would say, have personal elements to them. You want to have an emotional or character arc to the story. That’s what draws people. You probably don’t want to have too much of that in there, because people are not interested in your life and story enough by itself. But people generally are interested in the trials and tribulations of the human experience, and if you add that in a way that’s compelling, it’s going to amplify the message of the rest of the story.

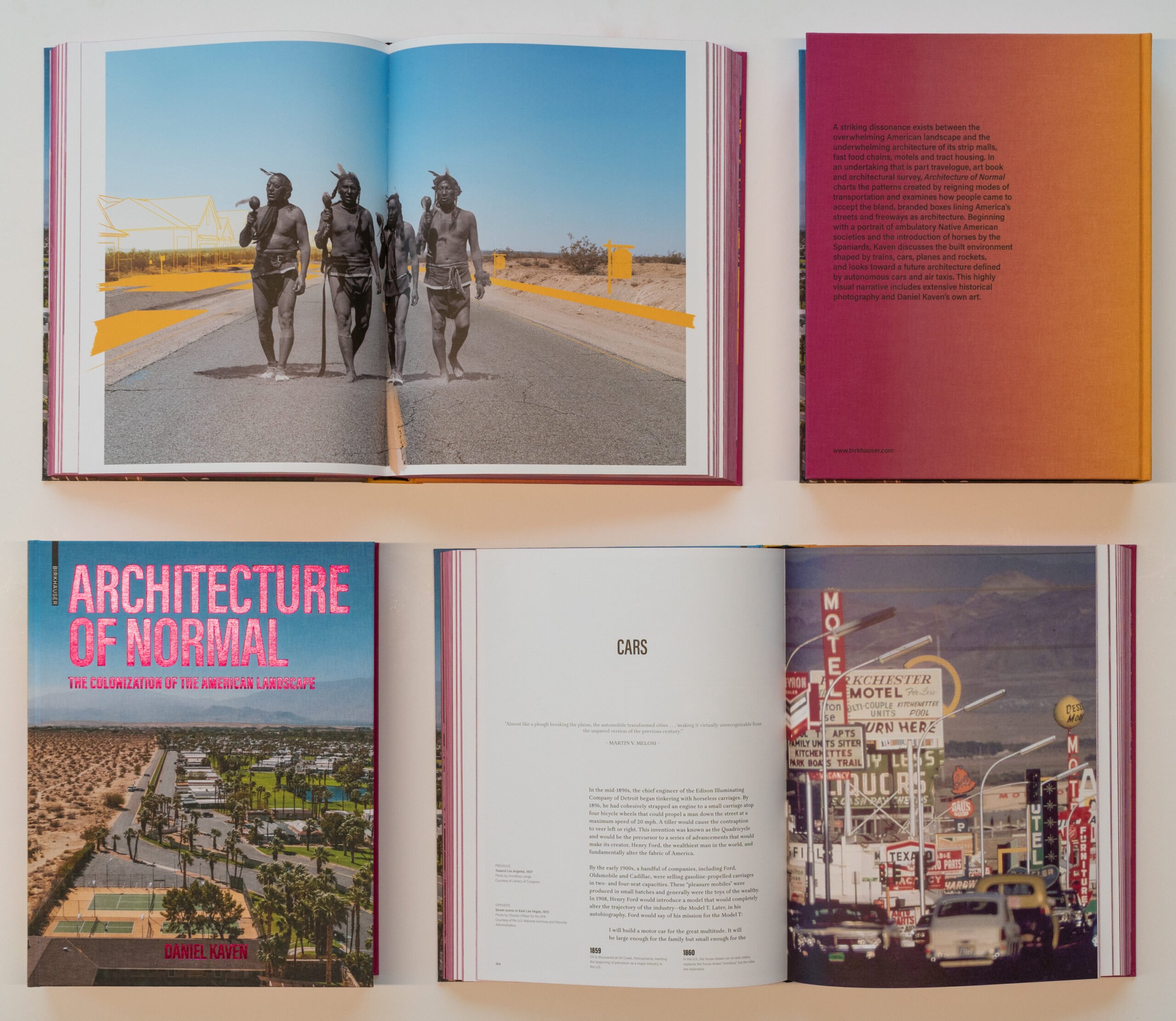

It was clear in those early posts that images would be as important as words. This is a great picture book as well as a history—almost like the best history textbook we never had back in school.

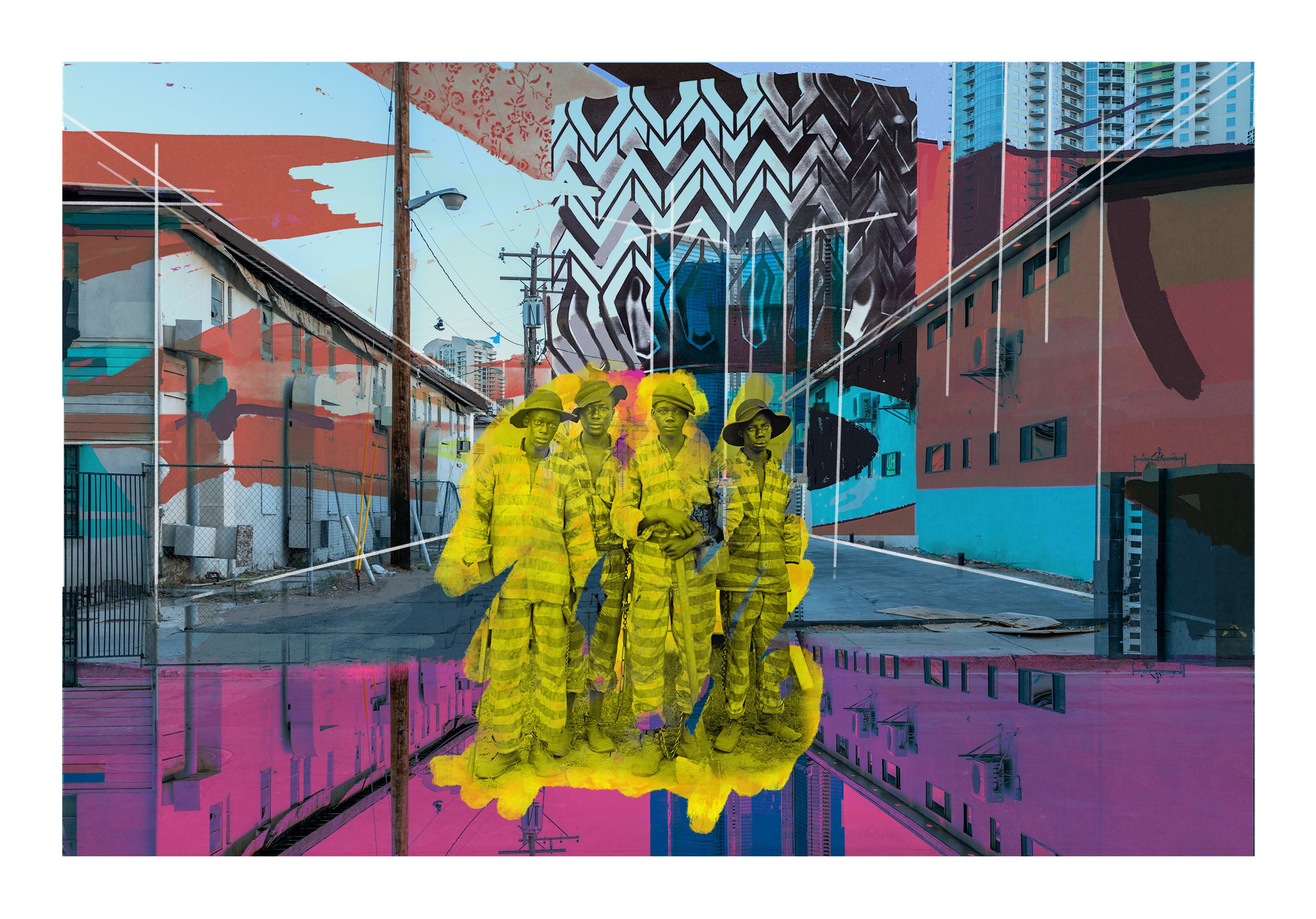

I actually thought of it as a kind of sixth-grade history, and my fifth-grade son is reading it now. That was a really important goal: to make the book something you could pick up and get something from in ten minutes. It was a copious amount of sifting through images in the Library of Congress and some other huge archives, finding the right ones to tell the story. There is a Dorothea Lange image of a woman with her children in the Dust Bowl, and I deliberately chose the less famous one in the series.

Albuquerque makes an interesting launching point.

I was born and raised in Albuquerque. My family’s been there for a long, long time, and my soul continues to live there in New Mexico. But at the same time, it’s really in my mind where America began, because it’s been inhabited for thousands of years. And yet it’s also where we’re testing a lot of today’s rocket technology. I like to think that this book or at least a book like it should be required reading for sixth graders, so they understand America and how it became to be, because, in a lot of ways, the physical growth of America is easier to understand than the political growth.

To me, Architecture of Normal is about how a rugged landscape became tamed by transportation and real estate.

America’s a big land deal. It’s as simple as that. As soon as we did the Louisiana Purchase, America just became a function of trying to sell parcels of land to Europeans. There were sales offices in Europe selling land to farmers in Europe and getting them to come here. The train lines built the track and every time they had a depot, they cut up all of the property nearby, sold it, and that’s how they paid for the railroad.

You actually coined a new term in the book: “derivatecture.”

It’s the productization of architecture, something from a cultural standpoint that just makes things the same everywhere, particularly with corporate chains. Like with a Home Depot, you can find the same bolts on the same aisle in the same building type in two different states, and that’s a strange, strange circumstance. Does the 76 station need to look the same in Albuquerque, New Orleans, and Nashville? I think it actually started with the Bauhaus and the International Style: creating a global architecture. But particularly in the automobile age, that sameness became crushing. Why would you want to travel anywhere if it just looked the same as where you already were? That to me is depressing.

What are your thoughts on Portland? A decade ago it was a kind of hipster capital. Today it’s battling problems such as homelessness and crime.

Portland has a real perception problem for sure, and I think that needs to be mended. That said, when people talk about America and its history, they talk about 1776, but the Western part of America is really no older than the Gold Rush. The population in the West was dismal before 1849. That is what spurred the trains to come across the entirety of America and to bring people out here. But Western America is an absolute toddler, maybe even an infant, on the global stage. I mean, that’s what makes it incredibly unique compared to a lot of other countries. Almost anywhere in Europe evolved centuries ago.

I’m curious about the word “normal” in the book’s title. What does normal mean to you?

That title just came to me, and I think it poses a question: what makes up the things that we consider normal in our lives? If you define what normal is, and what’s outside of norms, that’s very much a moving target over time. Like, what does a normal house look like? If you asked a child to draw a picture of a house, is it going to be drawn differently in Africa than in the U.S.? Definitely. Part of it is how have we come to know what is normal in our society from an architectural standpoint and why are we comfortable with it? Or why aren’t we comfortable with it? I guess a lot of it has to do with what I’ve witnessed in the expansive development of a lot of Western cities—Albuquerque, Boise, Salt Lake City, Denver—that are continuing to really expand their footprint. If you go out to the west side of Albuquerque or the suburbs of Denver, we’re talking wide boulevards, big parking lots, auto-oriented shopping experiences––that’s what’s become normal here.

The case the book makes is that the dominant transit mode decides the land-use, and thus what normal in that context is.

The moral here is: Technology gets ahead of us. It’s playing out right now with eVTOL [electrical vertical takeoff and landing] aircraft. There are hundreds of startups investing billions of dollars in this technology. Maybe at first, your own personal flying car will cost $1.5 million, and it’s just a toy for a few people. But then they’ll get that price under $100,000, and everyone’s going to want one. That’s what happened with automobiles. In the not too distant future, we’re going to have a sky overrun by drones and by flying cars. And if we don’t get a handle on what we want to come out of that, it’s going to happen again. We need to get ahead of technology for once and have a serious philosophical conversation.

Losing the peacefulness of the sky to hundreds of aircraft sounds like dystopia to me.

That reminds me of a Mark Twain quote in my book: “A railroad is like a lie—you have to keep building to it to make it stand. A railroad is a ravenous destroyer of towns unless those towns are put at the end of it and a sea beyond so that you can’t go further and find another terminus. And it is shaky trusting them, even then, for there is no telling what may be done with trestle-work.”

People felt trains would ruin the frontier. You could say they were right and it happened, or you could say those fears were overblown. But flying vehicles are going to happen. Can we design and think about it in a way that won’t ruin it for everyone? And honestly, the flying experience is pretty unbelievable. You get into a helicopter or anything that gets you off the ground and it’s a beautiful experience. And think of it this way: we spend trillions of dollars on roads and bridges. Imagine not having to spend that money. None of that money has to be spent in the sky.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

- No tags selected

Related

Profiles

Democracy Needs Room to Breathe

From reimagining Pennsylvania Avenue to reactivating Franklin Park, David Rubin and his Land Collective Studio are helping Washington, D.C. reclaim its public spaces as open, flexible, and deeply democratic.

Viewpoints

Perspectives on PVC: What Is the Path Forward?

Three experts offering distinct perspectives unpack the complexities—and possibilities—of designing with (or without) PVC.

Profiles

Salima Naji’s Quest to Preserve Culture Through Architecture

Salima Naji’s Quest to Preserve Culture Through Architecture. Across Morocco, the architect and anthropologist is rebuilding ancient buildings so that they may endure for generations to come.