May 22, 2017

Barbican Exhibit on Japanese Houses a Veritable Architectural Playground

A new exhibition at the Barbican Gallery highlights Japanese architects’ thrilling, seemingly impractical, sometimes topsy-turvy experiments with the house.

It’s rare to go to an exhibition with a climax as striking as the one that concludes The Japanese House: Architecture and Life after 1945, currently on view at the Barbican Art Gallery in London. Inside the split-level gallery, a 1:1 scale model of Ryue Nishizawa’s Moriyama House (2005) has been constructed, an expense that seems justified by the introductory wall text that describes the project, located in a Tokyo suburb, as one of the most important houses of this century. Visitors will feel themselves magnetically drawn to this architectural playground, where the digital fantasies of #minimalist photo streams can be fleetingly inhabited in person.

In reality, the Moriyama House is much more diffuse than the indivisible-sounding house would imply. Comprising a constellation of domestic spaces, the small compound is a kind of “village” of boxy units sitting independent of one another and shot through with outdoor corridors that lead directly to the street. The smallest unit is a simple bath/shower, while the largest is a three-story stack of living and sleeping spaces. In the Barbican, the latter is filled with an assortment of objects chosen by Yasuo Moriyama, a reclusive artist, himself—houseplants, slippers, a record collection, and the iconic “Rabbit Ear” chairs Nishizawa designed with his SANAA partner Kazuyo Sejima.

The Moriyama House doppelgänger and a second life-size construction, a specially commissioned teahouse and garden by Terunobu Fujimori, help elucidate the exhibition’s exploration of the spatial, socioeconomic, and material evolution in Japanese culture over the past 70 years. Taking the typology of the house—as opposed to housing more generally—as their focal point, curators Florence Ostende and Pippo Ciorra present projects from more than 40 architects, organized in chronological and thematic clusters. To Western eyes, nearly all fundamentally challenge our inherited notions of home and hearth.

What runs the risk of being random and disjointed emerges as a clarifying lens through which to consider the modern trajectory of the nation. The show charts an epochal course out of the dark days of World War II through the boom years of the ’80s to present-day Japan, a somewhat diminished world power but still a technological, cultural, and, of course, architectural trailblazer.

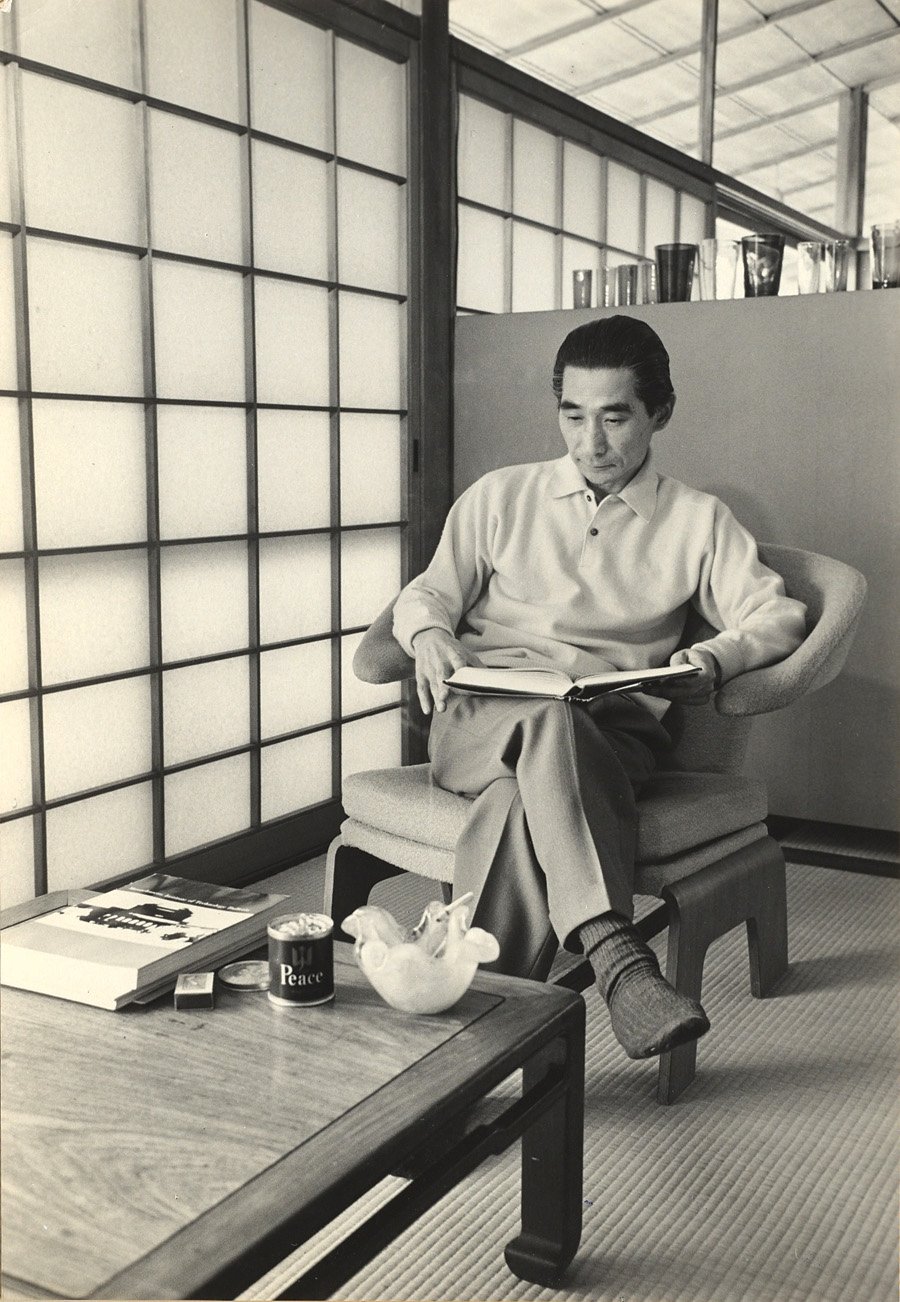

The scene begins at midcentury, with a selection of clips from Yasujiro Ozu films depicting middle-class domestic life, and there it stays for some time. Kenzo Tange’s house designed for his family in 1953 typifies the architectural debates of the immediate postwar era, when the search for a form that married Japanese heritage with the far-reaching influence of Western Modernism occupied practitioners from Toyama to Tokyo. With its raised living space, tatami flooring, and wooden pilotis, Tange’s house evokes both the Katsura Imperial Villa and Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House. (The influence of traditional Japanese architecture, in particular the use of light materials such as paper screens, on Modernist prophets such as Mies, Walter Gropius, and Bruno Taut is duly noted in the wall texts.)

Japan’s rapid population growth and urbanization through the 1960s and ’70s meant that spacious villas set in idyllic gardens such as Tange’s soon gave way to an architecture of hyperdensity. Takamitsu Azuma’s Tower House (1966) is a case in point and receives significant attention in the exhibition, with stunning large-format photographs and models lined with crinkled and faded newspaper that communicate the rough exposed concrete of this bizarre structure. Azuma’s house inverts the typically horizontal orientation of the Japanese home, with its fluid interchanges between rooms and passages, and reconfigures its living spaces along a vertical axis. Cutting an idiosyncratic figure, it makes ingenious use of a tiny plot in Tokyo’s Shibuya district.

Tadao Ando’s Row House (1976) also highlights the still-contemporary constraint of designing for confined urban plots by reinterpreting the machiya (town house). A domestic typology first developed in the Edo period (1603–1867), it consists of a street-facing workplace and a living area that leads into a small rear courtyard—all squeezed into a deep, narrow plot. Ando’s Row House, with its fine concrete facade and rectilinear form, gave the typology a more rugged Modernist gloss while maintaining the machiya’s spatial efficiency. Atelier Bow-Wow’s Split Machiya (2010) in Shinjuku, Tokyo, accomplishes the same feat but through a refined material palette of wood and mirrored bronze surfaces. In these examples, small green oases orient the lives of inhabitants, shielding them from the clamor of the city.

By contrast, Osamu Nishida and Erika Nakagawa’s Yokohama Apartments (2009) and Sou Fujimoto’s House NA (2011) draw the city in. Fujimoto’s house has no internal walls and is entirely encased in glass—looking more like an X-ray of a house—while the high-ceilinged communal space of the Yokohama Apartments is separated from the street outside by a simple vinyl curtain.

The intelligent use of open passageways, skeletal structuring, and close attention to light and shadows draws these projects into sharp relief with the heavyset Brutalism of the Barbican, yet the power of both is complementary. Just as the thrill of the Barbican’s concrete cityscape is grounded in the full sensorial experience of simply being there, the curators’ inclusion of the scale models fosters a spatial experience that architecture exhibitions nearly always lack. What’s more, it encapsulates the technical and material developments explored throughout the show: a study in footprint ingenuity, spatial economy, and imaginative joy, somewhere at once homely and otherworldly.