October 21, 2015

Between Modernism and Postmodernism? Hippie Modernism

The Walker Art Center’s “Hippie Modernism” takes seriously the era’s mantra-like invitations to “turn on, tune in, drop out.”

Neville D’Almeida and Hélio Oiticica’s installation CC5 Hendrixwar/Cosmococa Programa-in-Progress from 1973, which included colored hammocks, 35-millimeter slides, and an audio disc.

Courtesy Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis/T. B. Walker Acquisition Fund, 2007

Between the Modernists and the Postmodernists were the hippies. As a cultural moment, the 1960s and early ’70s are extraordinarily resonant with our own time—with echoes in organic farming, climate-change debates, digital communication, and the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s no surprise that the countercultural explosion has received attention in the design world recently, from the 2011 MoMA exhibit Access to Tools: Publications From the Whole Earth Catalog, 1968–74 to Maurizio Cattelan and Pieropaola Ferrari’s luscious book 1968: Radical Italian Design (Deste Foundation/Toiletpaper, 2014).

Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, which opens at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis on October 24, decodes the period, using a remarkable collection of art, architecture, and design. Curator Andrew Blauvelt has structured the exhibition using a phrase attributed to Timothy Leary, but originally uttered by Marshall McLuhan (one of the visionary demigods of the era, alongside the likes of Buckminster Fuller and Victor Papanek): “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” The “turn on” section, typified by the fantastic visions of Archigram, represents the opening up of society’s consciousness to other realities and possibilities. “Tune in”—the quest for information—explains the proliferation of magazines, posters, and books. Rebelliousness and refusal are the themes of the “drop out” section, where Blauvelt quotes Superstudio member Adolfo Natalini: “If design is merely an inducement to consume, then we must reject design.”

It’s that last part that makes the designs of this era so hard to define. Groups like Archigram and Superstudio grasped at a techno-fetishistic future while rejecting Modernism’s view of technology as progress; their most earnest efforts are tinged with satire or ennui. Blauvelt tries out the metaphor of the two-faced Janus—who looks to both past and future—to explain this conundrum, but finds that inadequate in the face of the era’s intellectual gymnastics. Then there is the question of its contemporary significance. In Blauvelt’s words, “Even half a century later, we still ask: are we any further?”

The catalog for Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia (Walker Art Center, 2015) is now available through D.A.P.

Clark Richert, View of Drop City, “the Complex,” in El Morro, outside Trinidad, Colorado, circa 1966

Courtesy Drop City PhotoArchives

Corita Kent, yellow submarine (1967)

Courtesy Joshua White

Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, Women in Design: The Next Decade, 1975

Courtesy Sheila Levrant de Bretteville

Superonda Sofa, Archizoom Associati, 1966 Archive Centro Studi Poltronova

Courtesy Dario Bartolini (Archizoom Associati)

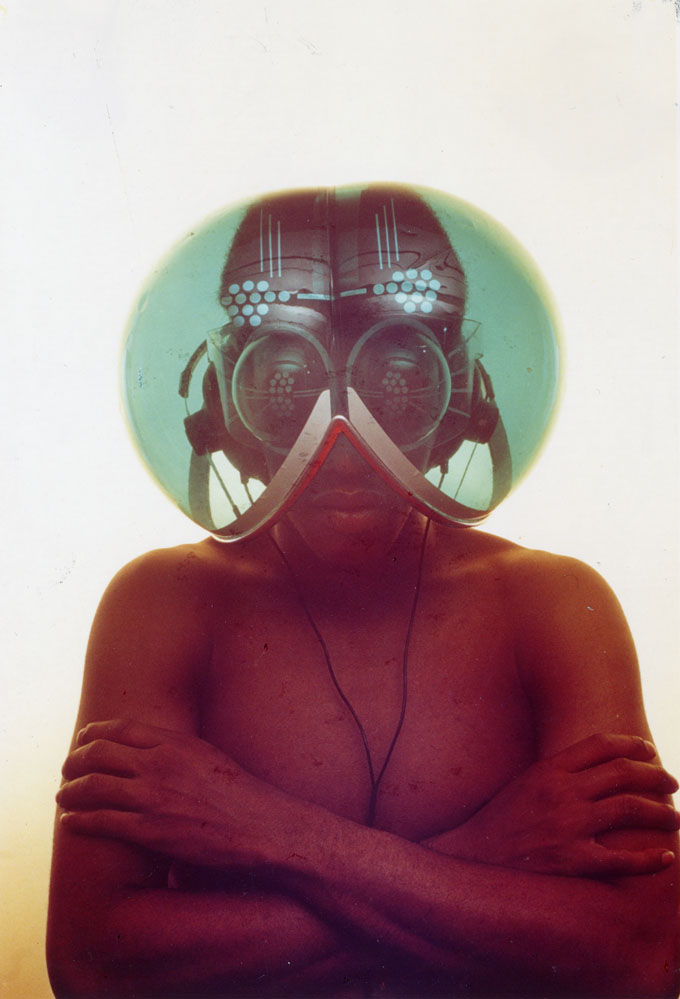

Ira Cohen, Jimi Hendrix (1968)

Courtesy Ira Cohen Archive, LLC