August 13, 2019

How Landscape Architecture Hoped to Save the City

An exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum explores the intersection of landscape architecture and social reform at the turn of the 20th century.

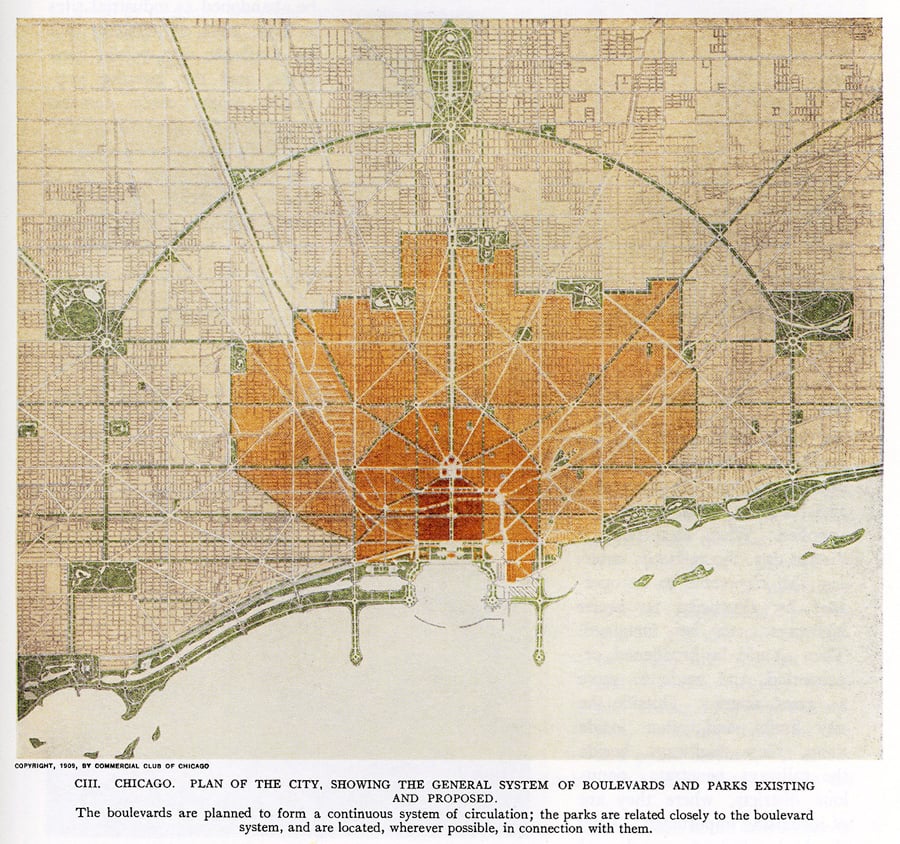

“Make no small plans,” goes the old urban planning saw. While the provenance of the quote is disputed, it’s generally attributed to Daniel Burnham, who devised city plans for Chicago, Washington, D.C., and San Francisco. But as a leading representative of the City Beautiful movement, Burnham was also something more—a reformer.

So, too, were the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, whose progressive politics had their roots in journalism, and his protégé Charles Eliot, who championed the creation of nature reserves.

Their stories, and those of contemporaries like the photographer Lewis Wickes Hine, are told in Big Plans: Picturing Social Reform, a new exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Hine’s photography gives a sense of the blight that had infected America’s urban centers by the dawn of the 20th century. To combat the ills of poverty, overcrowding, and sickness, reformers propagandized ambitious proposals to remake cities like New York and Boston, many of which feature in Big Plans.

In revisiting this period—the so-called Progressive Era—the show couples the emergence of landscape architecture as a discipline with political agitation, says curator Charles Waldheim. “As planners we’ve learned from the failures of Modernism, but we’ve also become allergic to the ‘big plan.’ We now seem to be politically returning to something, and the Progressive Era model showed one way you could connect politics to spatial practice.”

You may also enjoy “University of Texas at Austin Exhibition Explores the Arts & Crafts Movement in America.”