July 2, 2018

The Hamburger (and Chili Bowl and Donut) That Ate L.A.

California Crazy, recently reissued by Taschen, is an indelible record of the wild, wonderful tradition of roadside architecture.

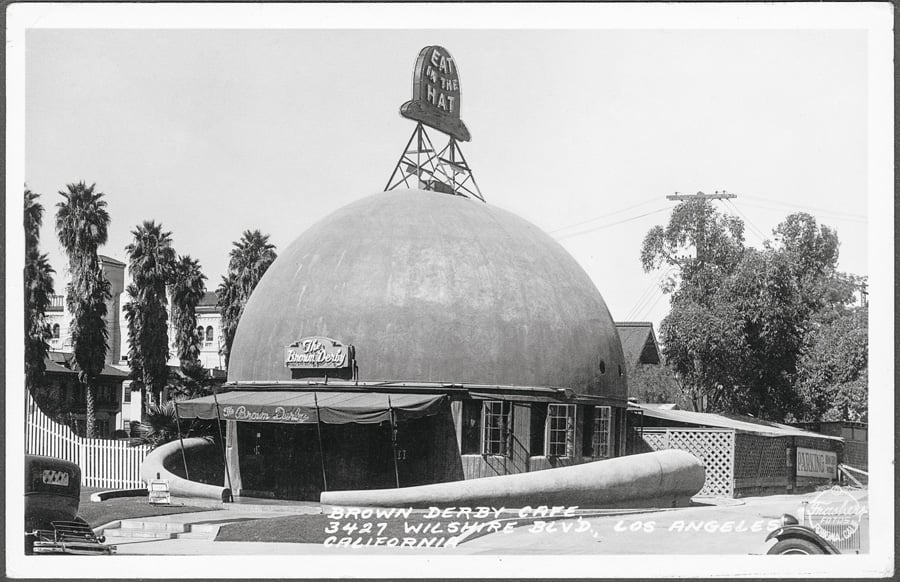

Anyone who has taken a road trip has had the experience of cruising down a highway and spotting a garish beacon beckoning you to pull off the road: a large shoe, a giant Paul Bunyan, a huge ear of corn. These advertisements for kitschy museums and miniature golf courses, hotels, and gas stations have been staples of the American road for decades. But as the nation’s car culture evolves (good luck driving what’s left of Route 66), these structures—and their architectural tradition—are disappearing.

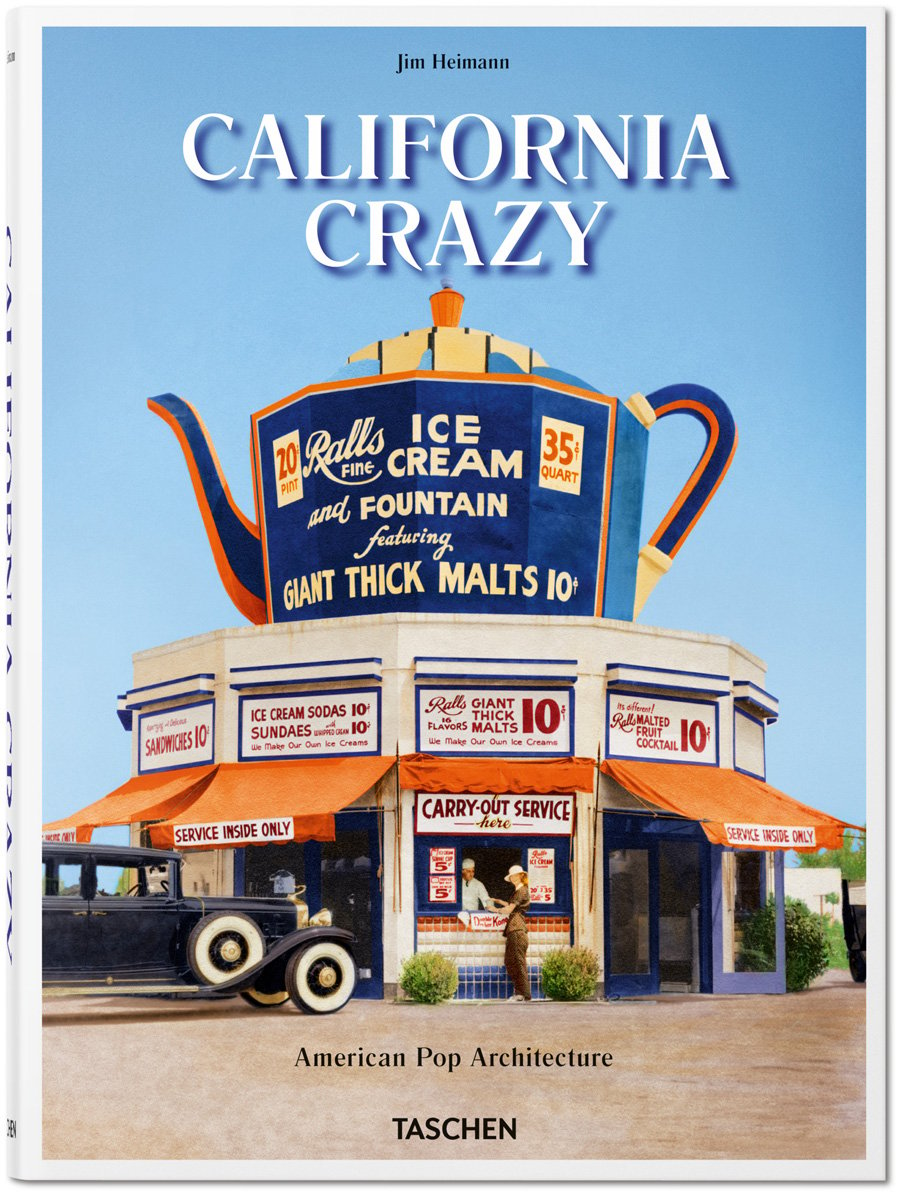

That makes California Crazy: American Pop Architecture resonate in a way its author, Jim Heimann, never expected. Originally published in 1980 as a slim, eight-inch square collection of black-and-white photos capturing California’s wild, weird, and wonderful roadside architecture, the book was released in June in an updated, gorgeously hulking volume by Taschen. The first edition had been out of print for nearly 20 years, but its impact never waned.

“It was a great little book, but for some reason it really struck a chord with a lot of people who still refer to it as being very inspirational,” Heimann tells Metropolis. “People still call me to say, ‘This book changed my life.’”

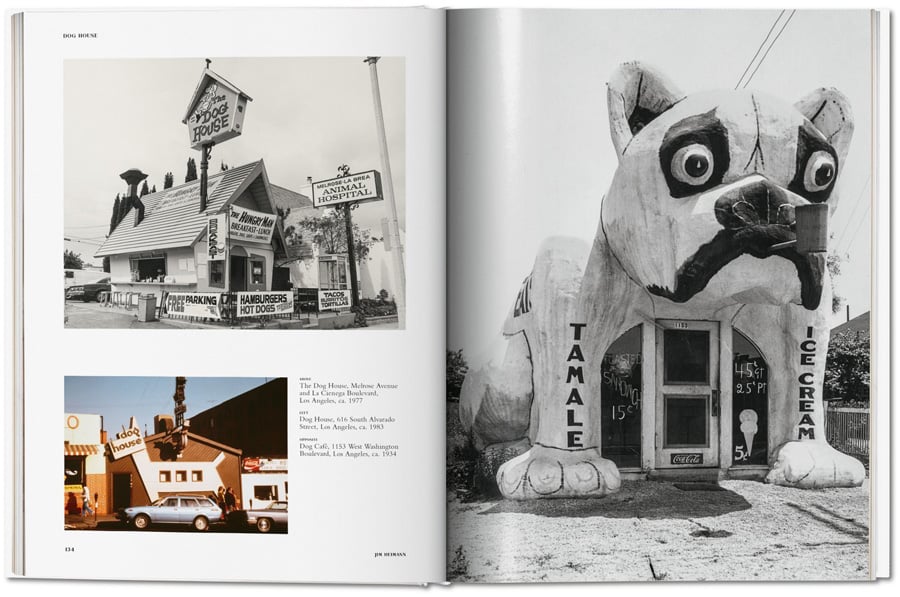

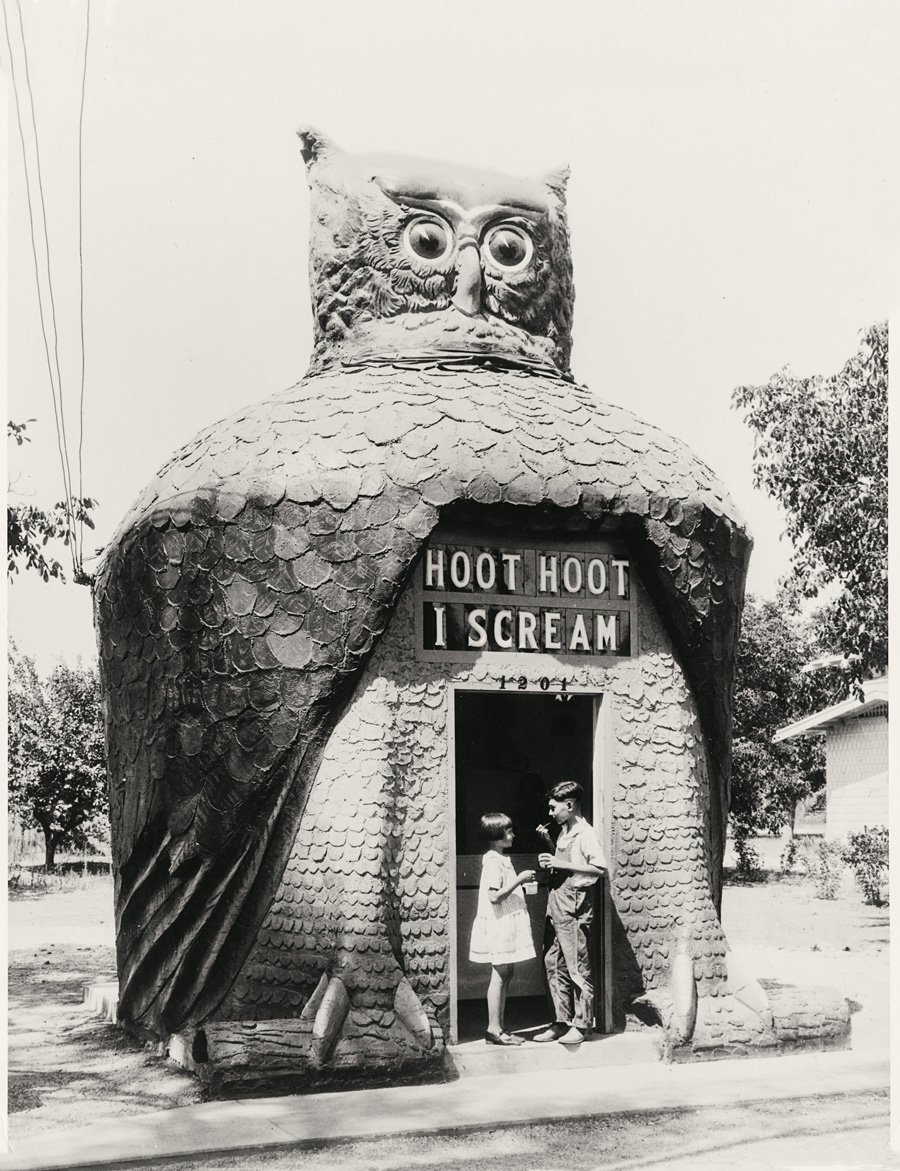

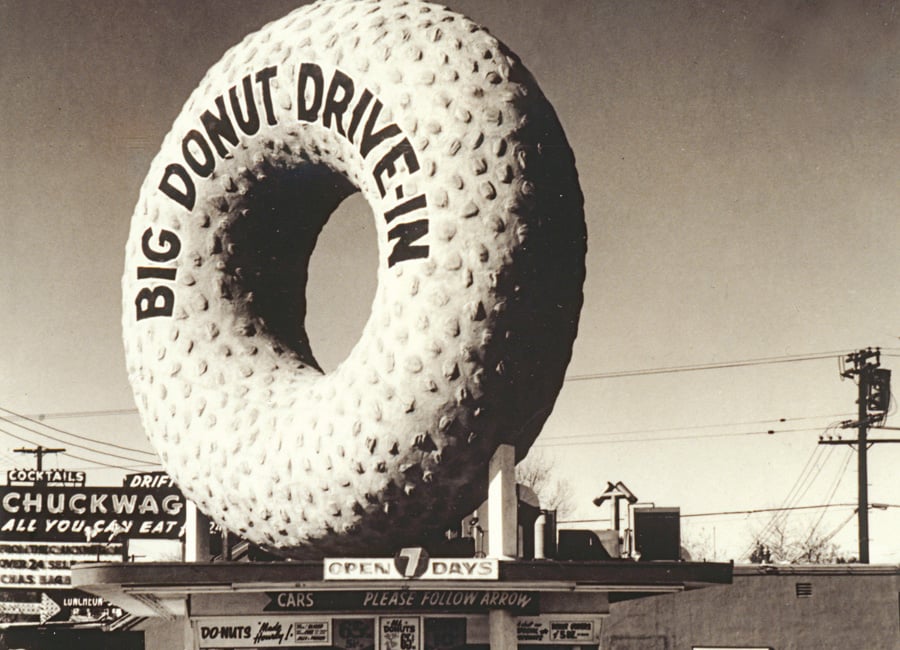

When he began working on the book, in the late 1970s, academically minded architects sniffed at such Pop buildings. But Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s seminal 1972 book Learning From Las Vegas sent shockwaves through the architectural community. It was an honest discussion of commercial architecture, and Heimann immediately connected with it. He had tried organizing a book of bygone Hollywood nightclubs from the 1930s and ’40s, but records were scarce. As he researched, though, he kept stumbling over images of a giant owl ice cream stand, a puppy-shaped hot dog spot, and huge donuts, oranges, and bowls. It forced Heimann to rethink, and ultimately drop, his nightclub project.

“There was nothing that had ever really looked at this kind of sub-culture of [roadside] architecture,” Heimann says. “When I read [Learning from Las Vegas], it all kind of hit. This is really a justifiable architectural category. It’s just that no one’s taken the time to look at it.”

Over two or three years of intense research, he gathered material anywhere he could for what became California Crazy. (University of California Santa Barbara architectural professor David Gebhard, a Southern California architecture specialist, contributed an essay, giving the book academic street cred.) On the cover was the Toed Inn, a hamburger joint in the shape of a brown toad (you ordered at its stomach and ate under its legs), and inside was a selection of evocative, super-campy mimetic buildings: orange-shaped orange juice stands, a piano and radio store inside a piano, the coffee-pot-topped Coffee Pot in Los Angeles.

“L.A. is basically the only city in the world created or really built around the automobile,” Heimann says. “Instead of doing your commercial chores walking on a main street, you’re going 35 miles an hour down a highway, so if you see a giant pig you’d imagine you’re going to get a ham sandwich, which was the case.”

For the new edition, Heimann added more images and contextual details—he has steadily collected two file cabinets’ worth of images and ephemera about these buildings—but he also augmented the scholarship. Since the book’s original release, more people have tackled adjacent topics—diners, coffee shops, motels, gas stations; Heimann himself did a book on drive-in restaurants—while students have studied and presented research on commercial architecture. All of that has given Heimann more data, photos, and materials to build out the roadside tradition.

Perhaps the most critical addition to the updated volume is the section on San Francisco’s 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. Thanks to recently published volumes, Heimann establishes a continuum between the exposition’s oversize ostriches, elephants, toys, and building blocks—created using a new, more malleable plaster compound—and the Hoot Hoot I Scream giant owl, with silent-era Hollywood in the middle. One visitor to the exposition was The Birth of a Nation director D.W. Griffith, readying the film Intolerance. He wanted to include a lavish Gates of Babylon sequence, and “he hired these [exposition] craftsmen on the spot, brought them to Hollywood, and put them to work building Babylon on the corner of Sunset and Hollywood Boulevard,” Heimann says. “It sat there and became kind of a tourist attraction after production, finally rotting away after 10 or 15 years.”

Between Babylon on Sunset and the close proximity of everyday people to the ungated backlots of the nascent studios, Angelenos became accustomed to weird and strange structures populating their streets. Soon such buildings became as commonplace as they were disposable, made cheaply and without an eye toward longevity. That makes the photos, napkins, brochures, plans, patents, and other artifacts gathered in California Crazy oftentimes the only record that the place existed.

That lack of permanence hasn’t helped so-called programmatic architecture’s reputation, nor does the fact that there were often no actual architects involved in its design or construction. Nearly 40 years after the original publication of California Crazy the mode has earned a bit more respect, and while it hasn’t been fully accepted, these buildings continue to proliferate, especially internationally: Three 30-story apartment buildings in China shaped like Ming Dynasty emperors; a giant sheep, pineapple, and koala bear in Australia; bus stops shaped like mushrooms and strawberries in Japan.

Heimann won’t take credit for legitimizing the form—he cites Learning from Las Vegas as the beginning of the interest in commercial architecture—but he does have a sense of pride in introducing these buildings to a wider audience and, with the new edition of California Crazy, another generation of readers. Still, he sees work to be done in pushing this kind of building over the top. “You don’t see in architectural magazines anybody doing a story on contemporary, weird, strange buildings,” he says. “Metropolis should say, ‘Let’s see what kind of crazy stuff is out there!’”

You might also like, “15 Postmodern Buildings That Helped Define Los Angeles.”