September 14, 2016

A Brief History of Affordable Housing in New York City

Affordable housing’s future depends on us learning lessons from the past.

Co-Op City in the Bronx, constructed in 1973. One of multiple Mitchell-Lama projects in New York City.

Courtesy David Schalliol

Affordable housing in New York is constantly invoked as an aspiration, rarely as a reality. This is despite the 178,000 units in government-owned or -operated buildings, and despite the hundreds of thousands in private, below-market-rate apartments. A recent book, Affordable Housing in New York: The People, Places, and Policies That Transformed a City, shines a spotlight on New York’s considerable existing, affordable construction, whose imprint is so large as to be unmistakably visible from an airplane or satellite.

The book, edited by New York-based professors Nicholas Dagen Bloom & Matthew Gordon Lasner, features contributions from a wide range of authors and academics and focuses on several case studies: projects examined through the planning and construction stages to their adoption by residents. While it certainly offers no instant cure for the present housing crisis, it is an excellent primer on the many efforts that have been made toward tackling affordability, with lessons both cautionary and encouraging.

Unique New York

“Massive, centralized, and expensive, America’s biggest metropolis condenses and magnifies social inequality,” the editors explain early on. “Its poor historically lived in the worst tenements anywhere this side of Dickens’s London, while sky-high prices meant nearly everyone, in every era, has endured deficiencies and inconveniences unimaginable elsewhere in the United States.”

The unique challenges of New York’s population density inspired strenuous efforts to remedy them, including one of the nation’s most extensive public housing systems. Even more unusually, citizens and government bodies launched a substantial variety of construction for the middle-classes, a demographic whose housing has never been much of a public policy concern in most American cities. The book takes an intriguing ambit in surveying both of these varieties of “affordable.” Indeed, “affordable” is carefully defined by the editors; it encompasses what is understood as public housing but also spans a far larger variety of housing that is not market-priced.

From Private to Public

The book takes a chronological approach, focusing on the distinct (if overlapping) phases that characterized the history of public and affordable housing in New York, beginning with early efforts that were entirely private and philanthropically-motivated. These varied from John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s Dunbar Apartments in Harlem, designed to offer low-cost housing to African Americans, to limited-dividend corporation initiatives, such as Sunnyside Gardens in Queens. Those who were most invested in the success of these early projects—i.e., limited dividend corporations—tended to have the least resources; those with the most resources, such as Rockefeller, eventually lost interest in these pilot projects.

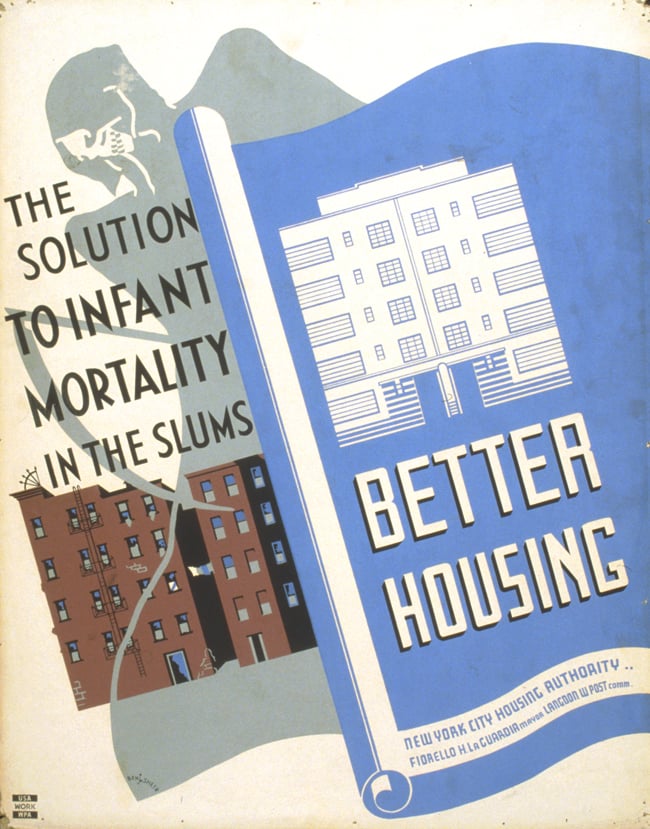

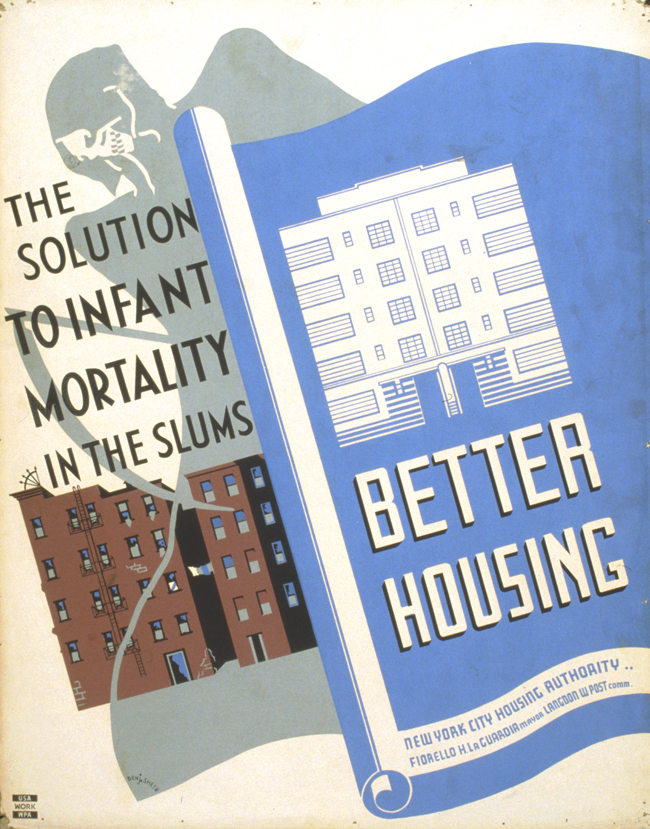

As it did for the economy writ large, the Great Depression upended the traditional American aversion to government involvement in housing. Progressive forces in the state and city aligned to create the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), the first of its kind in the nation. It was carefully crafted to legally accommodate a maximum digestion of public funding, and its work soon yielded a number of newsreel-like superlatives. The Williamsburg Houses were billed as the “largest and most expensive of the nation’s PWA housing developments”; the Queensbridge Houses, the “largest public housing complex in the United States”; and the Red Hook Houses, Brooklyn’s largest public housing development, spanned some 16 blocks.

NYCHA Poster, Benjamin Sheer, Federal Art Project.

Courtesy Library of Congress

The European Model: Its Pros and Cons

These housing projects emulated the European model of using mass housing as a solution for the middle classes as much for the poor, and, in early practice, the developments helped balance the poverty-relief pressures of federal authorities and NYCHA’s broader aims to house the working and lower-middle classes. NYCHA was interested in generating revenue that could be put back toward their own maintenance and so pursued mixed-income living scenarios, which were thought to be substantially more stable, and usually proved so.

If this was a forward-thinking policy that made for healthier housing developments, however, it came at the expense of the very poor and marginalized. In fact, some of the earliest NYCHA projects held as few as 5% of residents on “welfare tenancy.” Federal mandates increased this number to a minimum of 20% by the late 1930s, but most units were occupied by those with somewhat greater means. This balance has been an exceedingly tricky one over time; crime rates would often creep up with the substantial departure of working residents, and yet projects occupied mainly by the employed seemed to be missing the point of public housing. NYCHA also navigated a queasy realm of initially radicalized projects, with only a few open to African-Americans, and the effective quota formulas to maintain racial diversity in individual projects subsequently.

The European influence also extended to design, a concern impressively detailed in Affordable Housing in New York, which devotes ample attention to architecture as well as history. The Williamsburg Houses, built in 1938, were co-designed by modernist architect William Lescaze and featured Bauhaus-inspired detailing that set their design several notches above subsequent projects. They also eschewed the street grid of the surrounding neighborhood, establishing a precedent for subsequent decades of towers-in-the-park schemes. Interestingly, they also represented one of the first substantial incursions of housing into manufacturing areas, due to the cheaper cost of land. The Red Hook and Queensbridge projects, in particular, are both unusual instances of public housing spearheading deindustrialization.

Bloom and Lasner point out that “[by] 1955, 87,963 apartments had been built, housing a population of 335,000 people that was already larger than all of St. Paul, Minnesota.” The process indisputably delivered better housing units to many New Yorkers; it also dramatically altered many neighborhoods for the worse. East Harlem, the Lower East Side, and Brownsville saw local character replaced by what the editors call “NYCHA Modernism,” defined by the sprawling landscape of cruciform brick towers set away from the street. Developments rendered in this “style” tended to destroy the vast majority of businesses in their path and, paradoxically, often drove out neighborhood residents who would have gained from the new units. Even Robert Moses complained about their “monotonous sameness and institutional character.”

Rochdale Village in Queens, constructed in 1963. One of multiple Mitchell-Lama projects in New York City.

Courtesy David Schalliol

Catering to the Middle Class

In the 1940s and ’50s, the middle classes, who could afford to live elsewhere, increasingly did, contributing to the growth of suburbia. The city saw the construction of new modern urban homes and the provision of some degree of ownership—usually through a limited equity co-op—as vital to retaining New York’s middle classes.

Insurance companies made the first substantial forays into developing middle-class housing a decade earlier. Equitable’s Clinton Hill Apartments, Met Life’s Stuyvesant Town and Peter Cooper Village, and New York Life’s Fresh Meadows were envisioned as large, private enclaves with ready access to the city beyond.

Middle-income construction also received a vital jolt with the introduction of the Mitchell-Lama program in 1955, which provided a mechanism of financial support for middle-income housing construction.

The United Housing Foundation (UHF) and the Federal Housing Authority each built numerous Mitchell-Lama projects, many large enough to style themselves as municipalities in their own right, from Co-Op City and Starrett City to Rochdale Village. While boasting more amenities than public housing projects, most weren’t that far removed from NYCHA Modernism in external appearance. There are exceptions: Bell Park Gardens in Queens continued a much more traditionalist garden-apartment mode, and Rochdale Village even featured a Victor Gruen-designed mall.

Yet these complexes produced a mixed legacy. Some benefited from excellent locations, while others suffered from remote and inconvenient locations. Some attracted prideful communities that served as buttresses to their neighborhoods, while others, lacking this social infrastructure, declined about as rapidly as their surroundings did. Questions about the prudence of the support and construction of such housing rose as city and state fortunes fell. Bloom and Lasner write, “As the city’s finances collapsed in the 1970s, such a massive system of below-market middle-income housing appeared to many critics as the height of ill-considered government overreach.”

0-36 Eastwood, Roosevelt Island.

Courtesy David Schalliol

Exceptions to the Rule

The New York Urban Development Corporation (UDC), chartered in 1968 and headed by Edward Logue, impresario of northeastern corridor postwar urban renewal, set out to avoid the homogeneity of income, use, and design that had characterized the NYCHA Modernist projects since the 1940s (and arguably some of his own work elsewhere) by creating, mixed-income, mixed-use projects of architectural distinction. The 32 UDC projects produced before the charter’s dissolution in 1975 are among the most interesting in the city’s history of affordable housing, and ample evidence for the book’s argument that even if change has been slow in the history of affordable building in New York, it was never absent.

Roosevelt Island’s housing complexes, designed by Josep Lluís Sert and John Johansen, were showpieces of the program. The island’s planning dispensed with the wisdom of tower dispersal for a dense, collonaded main street lined with retail. The island’s original plan also contained a careful weighting of Mitchell-Lama units for a range of income types.

The Riverbend Houses in Harlem similarly sought to replicate traditional streetscapes—above ground level—with public balconies spanning the length of several five-story buildings, featuring semi-private stoops. Columbia University professor David Smiley, in an essay on the complex, details this arrangement:

“The front door of each unit and a small, low-walled patio were raised three steps up from the gallery, giving the space in front of the unit a distinctly more private sensibility. These front “yards” were, and continue to be, highly customized spaces; some residents used them as summertime sleeping porches, others set up their televisions outside, and still others fill their porches with elaborate gardens.”

Other projects took care to incorporate more existing urban fabric. The West Side Urban Renewal Area added new housing towers but preserved earlier rowhouses. The largely non-contiguous Twin Parks development in the Bronx filled 12 different plots with buildings by Richard Meier, James Polshek, Skidmore Owings Merrill, and others—all designed as infill, not as neighborhood surrogates in themselves. One new large multi-block development, Kenneth Frampton’s Marcus Garvey Village in Brownsville, embraced the street grid, adding additional “mews” or corridors scaled, as Karen Kubey writes, “to give the feeling of the nineteenth-century rowhouse district.”

5-25 Twin Parks NW, Bronx, 1973.

Courtesy Lo-Yi Chan

From the Past, the Future

Today New York remains exceptional in the amount of public housing it continues to maintain. Comparatively, many American cities built and then demolished extensive housing projects within a period of just 25–30 years. While crime remains an endemic trouble with public housing, New York has also managed its own stock far more effectively than many other cities, with genuine and sustained advances in safety achieved over the 1990s. The great distinction of New York continues to be the extent to which its public housing is occupied not just by the poor but by working families (47 percent according to a 2013 figure) and its considerable inventory of housing that is not public but below-market. This is a quantity that has only become more vital over recent decades of growth and gentrification.

But a survey of affordable housing in New York cannot help acknowledge the pressing present. Formerly regulated housing stock has steadily become market-rate; moreover, existing housing is often poorly maintained, and rents have continued to rise meteorically in every direction.

The book grants little attention to the larger reason why affordability is such an increasing problem for even middle-class New Yorkers: an insufficiency of construction. And yet, it’s difficult to disagree with the authors’ contention that even the most explosive of market-rate booms would not address the needs of the poor, who would require decades of overbuilding to realize cheaper rents. The core requirement for an expanded supply of housing for the lower and middle classes, the editors urge, is money, specifically “a mixture of long-term, below-market-interest-rate-loans, subsidized by the government; cash for operations and maintenance, especially for low-income housing; and low (abated) property taxes.”

There is no single simple fix, but Bloom and Lasner point to several ameliorative steps. Mitchell-Lama construction could be revived by the state. The city could replace the mortgage-recording tax with a transfer tax that yields more revenue for housing support. Organized labor could “reconsider its resistance to nonunion labor in the below-market housing sector.” If these goals are met, Bloom and Lasner argue, affordable housing in New York could experience a renaissance, if a vertically urban one: “[It] is hard to imagine large amounts of new housing in New York below-market or otherwise without high-rises—if not on the order of Singapore, then at least on that of Starrett City.”

The volume isn’t merely a compendious and fascinating history but also an argument, locating inspiration in the past for the urgent task of housing the ever-larger number of New Yorkers hard-pressed to live in the city. It is in such history that this book provides massive encouragement—anyone who thinks that large-scale affordable construction is impossible in New York needn’t turn to fantasies, they need merely look out their window.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025