January 22, 2020

Paris Exhibition Gives Charlotte Perriand Her Due

Inventing the Modern World foregrounds the French architect-designer’s inimitable talent, while also playing up her spirit of collaboration.

In 1936, Charlotte Perriand wrote a letter to Pierre Jeanneret, a frequent collaborator of hers, and his cousin Le Corbusier. “If I abandon the ‘profession of architecture’ in order to focus on problems more directly connected with life,” she wrote, “it is to be able to see more clearly into these problems, and also above all else it is because there was a barrier, a wall in our work…. The wall is cracked, and there is a whole new world that absorbs our interest, because ultimately, the Profession of Architecture is work in the service of humanity.”

This quotation appears fairly early on in Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World, the excellent exhibition on the French polymath that currently occupies all four floors of the Fondation Louis Vuitton (FLV) in Paris. Signaling a break from the Machine Age aesthetic she cultivated with her male associates, it reveals a lot about Perriand’s professional trajectory. Over the course of her long life, Perriand crisscrossed disciplinary boundaries—architecture, photography, textiles, furniture design—while retaining a seemingly voracious appetite for life.

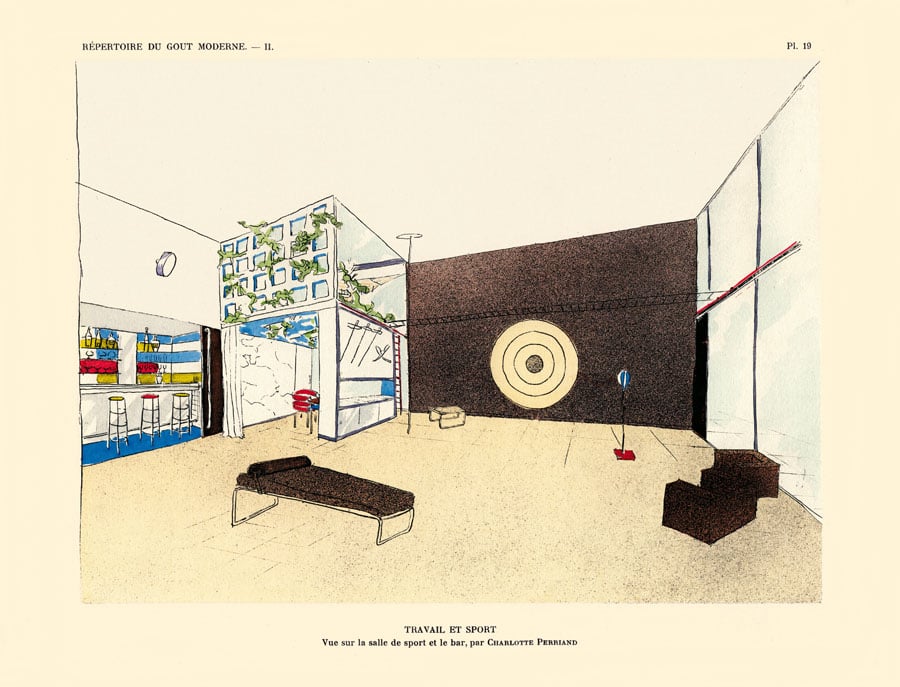

Beginning on the ground floor, the show is organized in roughly chronological order and proceeds from Perriand’s most recognizable works from the 1920s. The interior architecture of her Parisian studio at Saint-Sulpice, for example, exhibits early chair designs, with their distinctive bent-steel frames, and a somewhat obscure extendable table which appears to protrude directly out of its adjacent wall. It’s well-acknowledged that Perriand and other Modernists were ahead of their time, but still, more than 90 years after their invention, these objects appear revolutionary.

Moving into the ’30s, Inventing a New World illustrates Perriand’s deft work with images. There is La Grande Misère de Paris (1936), an extraordinary 52-foot photomontage depicting the arc of progress the Machine Age had ostensibly initiated, moving from the desolate housing conditions in interwar Paris toward a bright pastoral future. Tracking from left to right, photographs of wailing children in abject corridors gradually give way to a couple in embrace, walking through a landscaped garden. Stylistically, it’s akin to the Constructivist propaganda of the married couple Valentina Kulagina and Gustav Klutsis, or the cinematic murals of David Alfaro Siqueiros in Mexico City—and is just as striking.

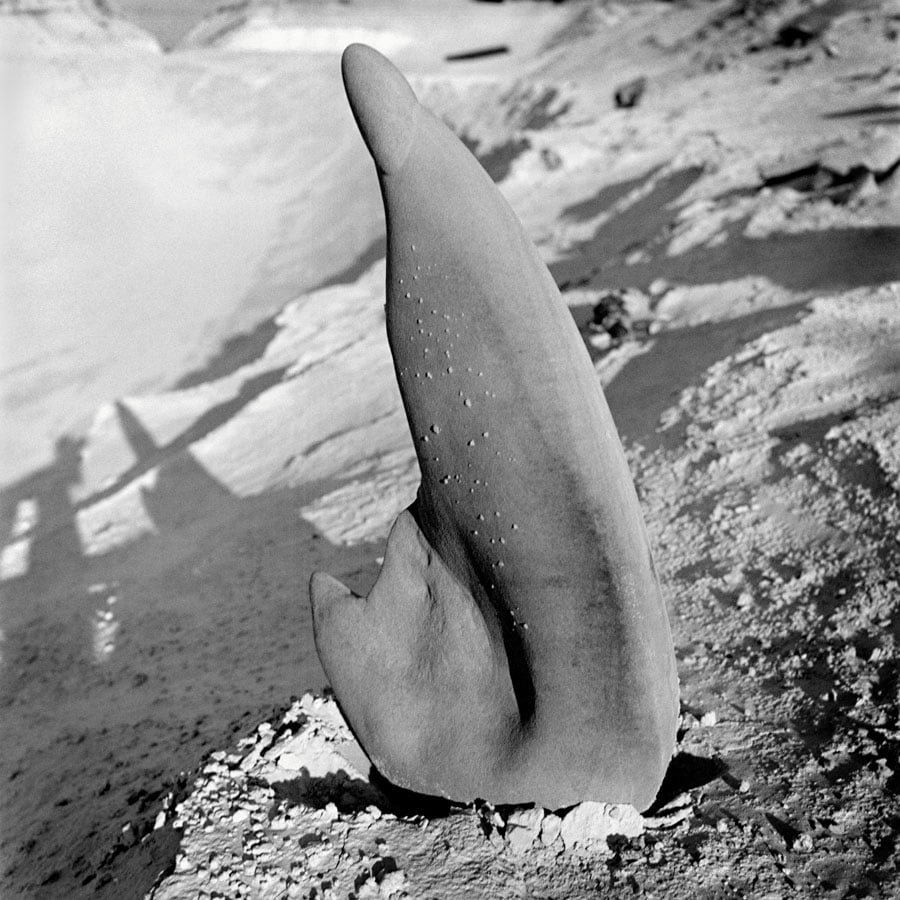

The focus on photography extends into the next section, which charts Perriand’s turn to the natural world for inspiration. Her minimalist “art brut” compositions—black-and-white studio images of animal bones, rocks, and metal scrap—are an unexpected highlight. This recourse to the naturalistic conditions her furniture works from the same decade, with thick timber replacing slender steel. Yet the same sinuous tactility remains intact.

From here, we move up a floor and on to Japan, a country with which Perriand maintained a productive relationship from the 1940s to her death in the late-1990s. Reproductions of pieces including the 522 Tokyo Chaise Longue demonstrate how she reinterpreted her classic works using bamboo and other locally available materials. Perriand’s prowess for timber engineering in combination with innovative spatial form comes through in pieces like the Banquette meander, or meandering bench, which comprises three connected seats. Displayed next to it is a rug bearing a fish motif; she transposed it from a sailor’s chalk drawing.

Into the ’50s, Perriand returned to Paris and trained her focus on “the art of dwelling,” the summa of architecture, furniture, and interior fittings. The furnishings of the Unité d’Habitation in Marseille by her former colleague Le Corbusier, for example, feature integrated storage and an open plan kitchen-cum-living room, allowing for the person cooking (then most likely to be a woman) to remain connected to the rest of the family.

Having grown restless in Paris, Perriand accompanied her husband Jacques Martin, a representative for Air France in Latin America, to Rio de Janeiro in the 1960s. Her furniture designs for their Rio home are familiar in their form—among them a rectilinear shelving unit and stylish low coffee table that are displayed at FLV—but are rendered in more expressive materials such as woven rattan. Later in her life, Perriand would complete more idiosyncratic works, which are on show at the exhibition. A bespoke ticket desk for the Palais de Tokyo is displayed in its full glory; an experimental modular bathroom and kitchen appear to anticipate domestic life on Mars; and her planning and full-scale residential works for the Les Arcs winter sport resort in the French Alps represent her most significant architectural projects.

Back on the ground floor, we might stop at the Chaise Longue B306. With its curved steel frame and black leather finish, the chair is a true icon of Modernism. At FLV it is displayed proudly alongside working drawings and the (perhaps equally iconic) photograph of Perriand lounging, gazing away from the camera and toward her projected silhouette.

Today, the authorship of the chair is credited to Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, and Charlotte Perriand, three apparently equal members of Le Corbusier’s studio. Indeed, throughout the exhibition, Perriand’s work is couched in the language of collaboration. Corbusier is, unsurprisingly, heavily present, not just in the architectural projects he completed with Perriand, but also in standalone tapestries and paintings that accentuate her furniture pieces. Works by Fernand Léger and Alexander Calder are also prominent. In fact, such is the Modernist emphasis on collaboration that the billboards advertising the exhibition around Paris depict the back of a topless Perriand surrounded by the names of famous men: Picasso, Miró, Braque, Delauney. Glimpsing the advertisement from the street, you’d be forgiven for misidentifying the exhibition’s subject.

Misdirected design and marketing aside, the curatorial focus on collaboration does actually make for a very good exhibition. Perriand was a highly sociable professional who worked well with others. In addition, her projects are imbued with that “service of humanity” she described more sensibly than her colleagues; what, after all, would the Unité d’Habitation be without those interiors? What’s more, a life’s work as rich as Perriand’s is inevitably entangled with many creative contexts and collaborators. Particularly in this context of high Modernism it’s a pleasure to see the co-mingling of her shelving units with, say, a Léger tapestry; neither need exist in isolation.

The question remains, however, whether the generous space afforded to other artists in a show devoted to a woman would be similarly given to women in a show about a man. The celebration of the solo male genius is a prominent trope that has had the effect of erasing dozens of important women designers and architects from the canon. Perriand is one of the more notable among them; for decades her role in the design of the B306 Chaise Longue was hidden behind the monolithic name of Le Corbusier. This pattern is rightly being dismantled, in part through the staging of monumental exhibitions, such as Inventing a New World, about exceptional women, such as Charlotte Perriand.

Charlotte Perriand: Inventing a New World is on view at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris through February 24, 2020.

You may also enjoy “You Can’t Spell SOM Without Gordon Bunshaft.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025