December 22, 2014

The Cold Rush: Designers Begin Looking to the Arctic

As the Arctic melts, pioneering architects and planners design for the ultimate extreme climate.

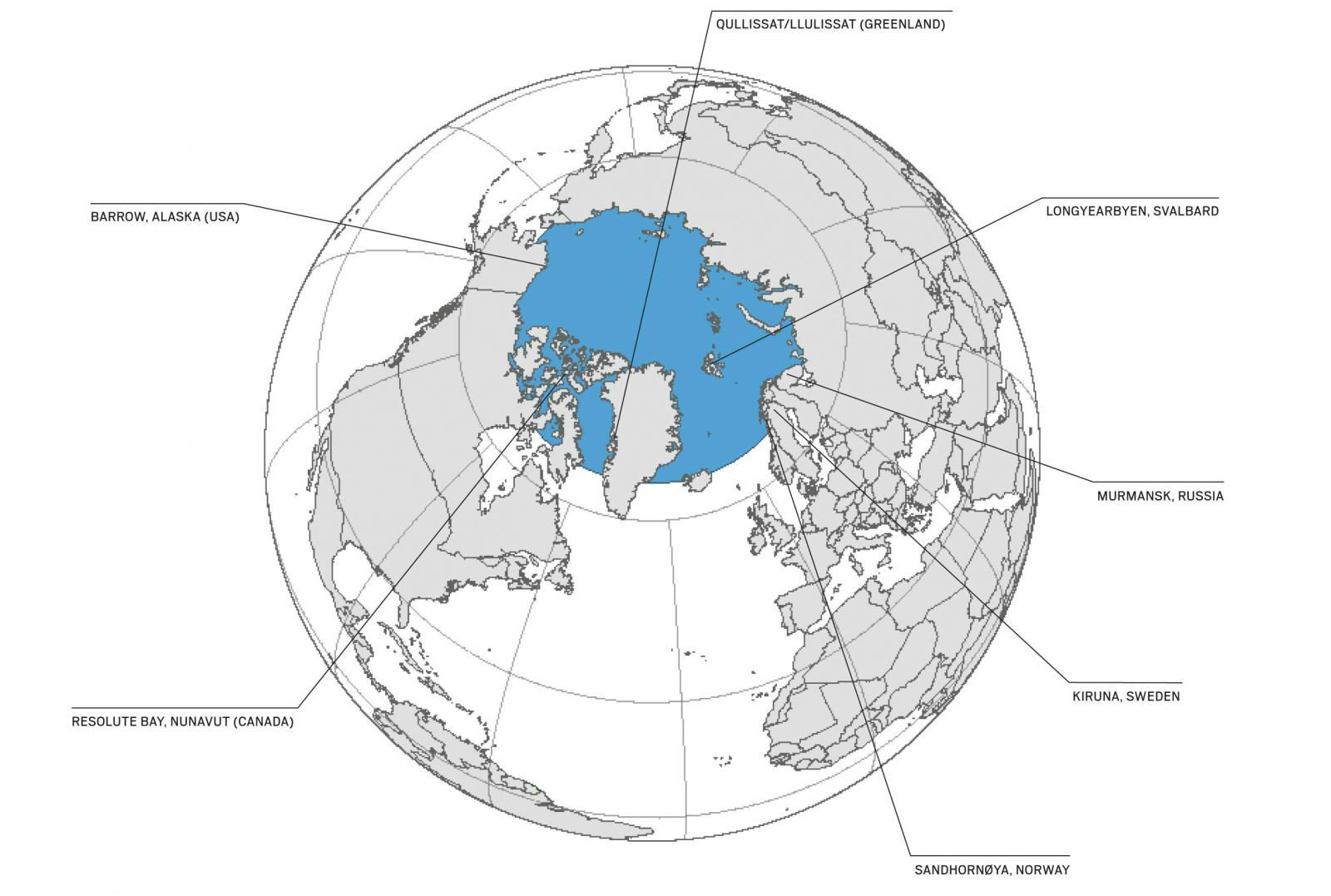

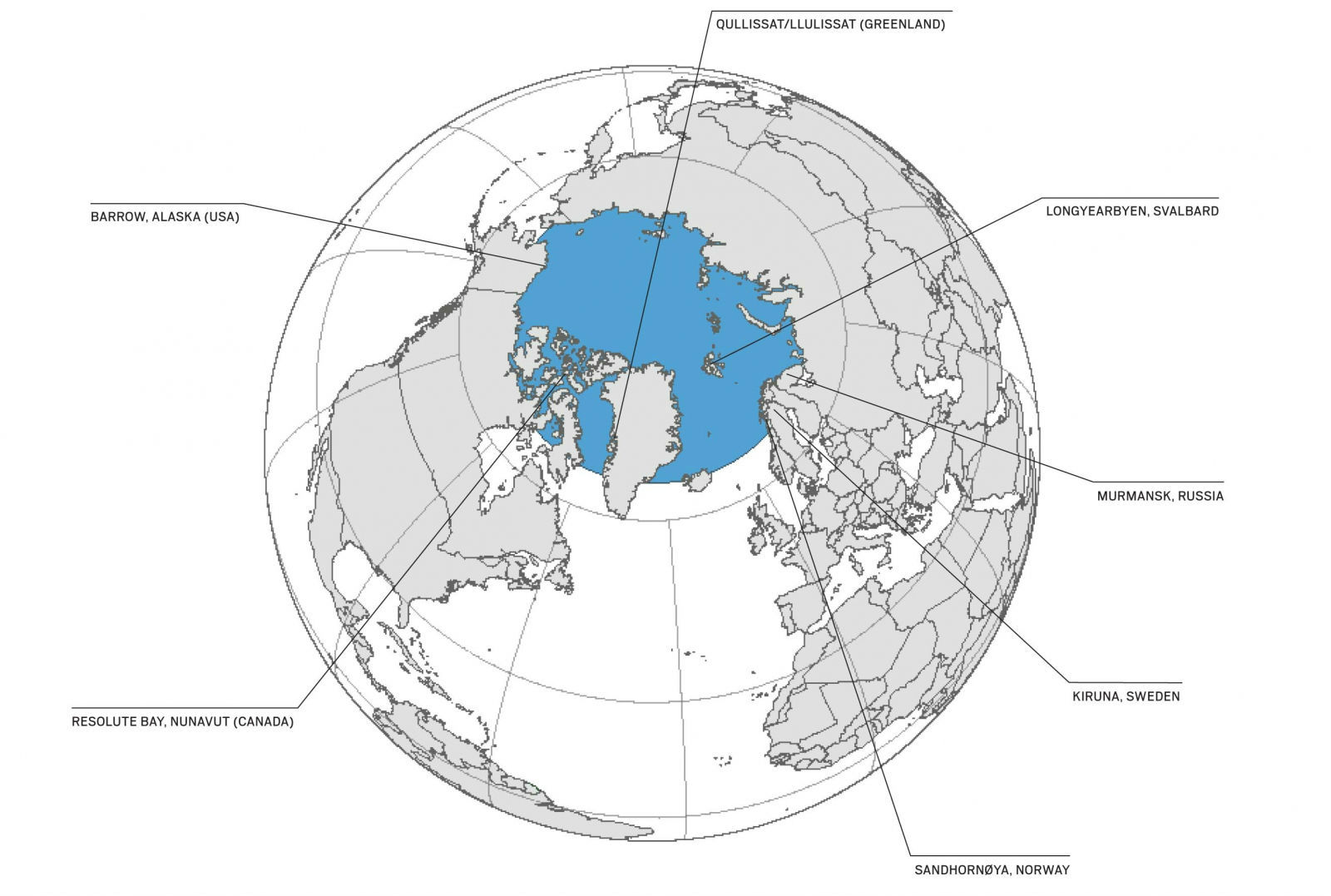

The Arctic (outlined in blue) is generally determined by the latitudinal line that wraps around the world at 66.5° North.

Just 400 people, mostly fishermen and their families, live on Sandhornøya. Dominated by craggy mountains, the island fastens to Norway’s Arctic coastline, a littoral zone pockmarked with fjords. Its remote location—Sandhornøya is an hour and a half from the next sizable town—and northerly latitude belie its relatively mild summers, varied landscape, and rich wildlife. “On walks, you’re likely to meet not just one, but several elk, deer, and birds like sea eagles, puffins, and ravens,” says Helga-Marie Nordby, an arts curator who splits her time between Oslo and Berlin. She discovered Sandhornøya when scouting sites for her latest project, SALT, the first festival devoted to Arctic culture, and settled on the place after stumbling onto its pristine white beaches. “When you step onto the beach, something profound happens to you,” Nordby says, recalling the island’s special aura.

Whether in Scandinavia’s lush Lapland, the barren frostscapes of the Canadian High, or Svalbard’s polar bear–ridden terrain, visitors to the Arctic often experience a similar reaction. (Indeed, eco-tourism is fast becoming one of the Global North’s prominent industries.) It’s the feeling that the beholder has breached an otherworldly landscape—all snowcapped mountaintops, breathtaking horizons, and virginal waters that must obviously signify profundity. An unknown place whose indigenous peoples—Inuit, Iñupiat, and Sami—are keepers of some mute wisdom, which finds expression in a very localized, preindustrial way of life.

This is the Arctic, or at least one version of it. In reality, however, there are two competing concepts of the Arctic—the Imaginary North and the Really Existing Arctic. In the former telling, the North still commands an intoxicating aura of the new frontier, an untapped territory that hasn’t much changed since 1960, when John Wayne launched the first Cold Rush in North to Alaska. (“The rush is on,” the country singer Johnny Horton cooed in the film’s title song.)

Sandhornøya, Norway

Launched in late August, SALT bills itself as the first festival devoted to the Arctic region. The festival will travel to other Arctic places in Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Russia, Spitsbergen, and Alaska in the coming years. On opening weekend, visitors sat on the beach to admire the Northern Lights. Top and bottom right: Further north, in Alta, the town’s cathedral, by Schmidt Hammer Lassen and Link Arkitektur, is dedicated to the lights.

Courtesy Gunnar Holmstad

Our attitudes towards the coerced migration and settlement of the Inuit, and ecological exploitation by means of resource extraction may have since refined; surely no one wishes harm or extinction on seals. Yet, leaders and enterprising industrialists of the developed world, reprising Cold War hostilities, jostle for possession of northern lands. Russia, which provocatively staked a flag in the seabed beneath the North Pole in 2007, remains the “conniving” hand at the table, while China, an “Arctic observer,” looms just behind. On the other side lies a seemingly unified, liberal front of European and North American parties, with Canada most actively reclaiming its Arctic sovereignty.

It’s not just oil, natural gas, and precious minerals at stake, but also shipping and trading routes that will ostensibly cut down on distances from East to West. The fact that these resources will not so easily reveal themselves—despite the thinning of the ice cap in and surrounding territories like Greenland and Nunavut, which border part of the fabled Northwest Passage—does not deter the profiteering zeal to drill and excavate. The North is melting, but it still poses an incredible challenge to wayward industrialization and colonization.

Conditions such as these begin to describe the Really Existing Arctic, a place that many architects and cultural creators have chosen as their arena of study and exploration.

In this often-polarizing context, the label “architecture” generally connotes tasks or works of engineering. “Architecture in the Arctic becomes consumed with technological and engineering ‘problems’ above a certain latitude, depending on climate and remoteness,” says architect Mason White of the Toronto-based Lateral Office, which has been active in Canada’s northern territories for nearly a decade. “Architecture can’t really survive here.” This gives practitioners little wiggle room to design and build, leaving them to assume other identities in order to uncover overlooked issues and opportunities for architecture to intervene. This year’s Venice Biennale, for instance, found White and his partner, Lola Sheppard, in the roles of planners, ethnographers, and cultural workers. The architects organized the Canadian Pavilion exhibition, Arctic Adaptations: Nunavut at 15, which filtered modernity through the lens of the Inuit habitus. The installation took traditional Inuit migratory patterns and its mobile culture as the framework for new architectural and urban interventions that would address problems of contemporary life. “Part of what we are interested in is repositioning the architect from a professional who simply responds to a given brief,” Sheppard says, “but, rather, acts like a spatial and cultural detective.”

Resolute Bay, Nunavut (Canada)

The indigenous town is inhabited by just 198 people whose homes are arranged in a semi-suburban configuration, which architect Mason White calls “compact Arctic urbanism.”

Courtesy Norman Dove

The Arctic architect should be an anthropologist, says Gisle Løkken, principal of Norwegian firm 70°N arkitektur—so named for the latitudinal line where the Norwegian Arctic begins. “Anthropological methods,” he suggests, “provide knowledge that is extremely useful for those who want to exceed the traditional design focus in architecture.” Having built widely in Scandinavia, Løkken has applied this methodology in places like Maniitsoq, Greenland, an economically depressed town with a shrinking fishing industry. In a snub to Denmark, Greenland’s Western lifeline and chief subsidizer, the municipal authorities voted to build an aluminum smelting plant. The project would open up the isolated town, which Løkken points out lacks a basic road system, to industrialization, thereby, presenting a grave threat for the local Inuit community. “The culture will undergo a transformation of cataclysmic dimensions, changes beyond possible return,” Løkken says. After working with community representatives to prevent this outcome, 70°N proposed a comprehensive “strategy” that prescribed a densification of Maniitsoq, in addition to a more robust vehicular and urban infrastructure.

For David A. Garcia, principal of Copenhagen-based MAP Architects, the Arctic’s frontier conditions offer more stimulating challenges than typical building commissions do. In Svalbard, an Arctic archipelago where polar bears outnumber people, Garcia was forced to contend with mediating that relationship. He proposed the Polar Bear Alarm, an electric, laser-emitting booby trap that didn’t physically try to contain or stop a charging bear (if you see one coming at you, it’s probably too late); instead, the “soft” barrier would sound off or flash lights when crossed. “I think there are other interventions that are just as spatial—perhaps not as large, perhaps more temporary—that can address these kinds of problems in a much better way,” he says.

Longyearbyen, Svalbard

Principal MAP Architects principal David A. Garcia inspects the Polar Bear Alarm he developed for settlers on the island, where polar bears outnumber people.

Courtesy MAP Architects

To think in this way requires a new type of architectural education. Toward this end, several newly established architectural programs seek to train pupils to balance large-scale interventions with agile thinking and an appreciation for geography. In September, Garcia inaugurated the first Masters of Architecture and Extreme Environment at the Royal Danish Academy’s School of Architecture, of which he is now director. The program, which Garcia had previously overseen at the Bartlett, University College London, and Lund University, gives students firsthand experience with an often remote site, asking them to develop their own narrative constructs to frame any possible spatial intervention or similar course of action. Garcia believes this on-the-ground approach—he plans to take classes to Greenland’s east coast and Iceland—equips students “with a methodology where they can’t avoid listening to context.”

Over in Norway, at the Tromsø Academy of Landscape and Territorial Studies, Janike Kampevold Larsen leads Future North, a kind of mapping project of Nordic Arctic communities through the application of different media tools. Larsen’s curriculum is hinged on “territorial management,” an umbrella concept that outlines the actual space of the Really Existing Arctic, mapping the High North’s tractable lands and, perhaps more valuable, its increasingly monitored sea passages. “Part of our work insists on stressing the ‘normality’ of many Arctic and Subarctic settlements,” Larsen says. “The landscape architects we produce at the academy are trained to consider large-scale interventions that facilitate and remediate the meeting of vulnerable landscapes and heavy industries.” The agenda is pragmatic, shying away from speculative design, and its contents owe more to field research than to traditional architectural protocol. The group has operated in areas of Scandinavia and the Kola Peninsula, collecting ecological data about existing industrialized regions as these towns and cities deal with both dwindling populations and production. Most mining and petroleum activities will be relatively short term, Larsen says, referring to the region’s chief industries. “We like to think of ourselves as present-day explorers of areas that are already known, already formed, but that are reshaping and need to be anticipated in a way.”

New civic buildings are rising up in the settlement that defy the challenges of building on permafrost. The population lives with the anxiety of Longyearbyen’s vulnerabilities, says photographer Wes Milholen, who is preparing a book on arctic architecture. “If the power plant were to fail in the winter, there are planes lined up ready to take everyone away in the middle of the night.”

Courtesy Wes Milholen

The Arctic Design Institute (ADI) at the University of Virginia School of Architecture mines similar territory. Founded by architects Matthew Jull and Leena Cho, ADI is the first design research platform of its kind in the United States. It counts among its members not just students and faculty from the school of architecture, but also representatives from the environmental sciences, law, and even musicology. The overall intention is to link design with natural and social science studies of the Arctic as it approaches a turning point in its cultural and industrial history. “The eclectic narratives of the group’s work show that the Arctic is a dynamic, transnational, connected, and contested place,” says Jull. In this vein, ADI often contemplates the various trajectories open to the Arctic’s urban communities. One recent project used China’s overt interest in the region, both for its network of shipping routes and growing tourist appeal, as a launch pad for a massive resort town on the Russian-controlled Yamal Peninsula. The design assumed the quasi-urban form of the Forbidden City, updating it to the Northern climate. Another project dwelled on the Russian city Norilsk and its inability to humanely house the migration workers who flood, and subsequently evacuate, the Arctic’s ports and mining towns every season. Ultimately, the designers focused on the necessity of sociable public spaces—an urban amenity fairly uncommon in Northern settlements and cities—and proposed a “Bizarre Bazaar” to cater to the leisure and cultural needs of transient workers.

Along these same lines, Jull and Cho, who run a parallel design and research office called Kutonotuk, have developed comparative studies of the competing planning ideologies that exist in the urban North. “Arctic urbanism can be simplified into three camps—what you see in North America, what you see in Russia, and what you see in Europe,” Jull explains. It’s an elegant distillation of a region whose development has been remarkably uneven. When speaking of Arctic cities, terms such as “urban” and even “city” become easily warped. For example, there is an incredible disparity between settlements in Nunavut, whose peculiar suburban formations accommodate populations of a couple of hundred, and the virtual mega-cities of Russia’s Arctic possessions, such as Murmansk. Today home to 300,000 people, many of them housed in the type of slipshod concrete-panel housing blocks championed by Khrushchev, Murmansk is easily the largest and most active Northern port. “Imagine Hilberseimer’s High Rise city crossed with Mordor, and then put it in the middle of a frozen open tundra,” Jull says.

Murmansk, Russia

The largest Arctic city, Murmansk is unique, not least due to the prison labor necessary to its formation. “It benefits from being an unscreened port all year,” White says, a rare condition in urbanized parts of the North American Arctic. This terrain, formerly the outlying reaches of the USSR, is most accurately termed the Really Existing Arctic.

Courtesy Matthew Jull

It’s a bleak image, and life is certainly tougher there. “Russia is really the urban arctic,” White agrees, describing the expanse of the really Really Existing Arctic. “But it’s also incredibly polluted.” It’s telling that the city’s life-expectancy rate is 13 years below the Moscow average. Comparatively speaking, the same figures for the Scandinavian Arctic, in cities like Vardo and Kiruna, are tantamount to those of Oslo or Stockholm. This equity is often reflected in the architecture of these cities, says Krister Lindstedt, an architect at the Stockholm office of White Arkitekter, Scandinavia’s largest architecture firm. Lindstedt has overseen an incredibly ambitious plan to relocate the town of Kiruna, a major, but now faltering, mining hub with a population of nearly 19,000.

After more than a century of iron-ore extraction, the grounds beneath the town are rapidly shifting, causing movements that will eventually render a large part of Kiruna’s existing urban settlement uninhabitable. By moving the town eastward, Kiruna officials hope to evade building collapses, and prevent the departure of its youth. “The relocation gives Kiruna an unparalleled opportunity to reinvent itself,” Lindstedt explains. The architects polled locals about what they would want from their new town, all of them felt the new urban arrangement “should have a closer relationship with the surrounding landscape,” in addition to offering cultural amenities. Renderings of White Arkitekter’s plan, dubbed “Kiruna 4-ever,” depict a winter wonderland, with townsfolk congregating in the picturesque central square. According to Lindstedt, the new Kiruna, with its smartly laid-out corridors and sustainable townscape—the buildings, wonky renditions of vernacular houses and civic architecture, are appropriately jolly—will contribute to and even encourage public life. Moreover, the plan’s attentiveness to its surroundings doesn’t just benefit the mining community. New constructions will preserve the terrain so as not to disturb reindeer herding, the local economy for the indigenous Sami people and “of cultural significance to the region.”

Kiruna, Sweden

Deep drilling has destabilized the land in Kiruna, Sweden’s northernmost town and its key Arctic foothold. A master plan for a new town center, by White Arkitekter, will move it eastward and establish a new network of streets and buildings.

Courtesy White Arkiteker

This sensitivity to environmental context and the concerted, if paternalistic, impulse to socialize community members are core urban values shared by the Nordic nations. The consideration of the indigenous population, too, is unique among Arctic societies, which have traditionally denigrated the native way of life. In 1999, four decades after the High Arctic Relocation—a virtual land grab in which Canada used Inuit families as proxy settlers, giving them little support or means of survival—the Canadian Parliament formally acknowledged Inuit land claims to the Northwest Territories and established the territory of Nunavut. Largely a symbolic gesture, the Inuit there are impoverished, often living in stranded, ill-supplied communities that bear similarities to the reservations of the American West. Nevertheless, the Nunavut Act that ratified the land transfer bolstered indigenous efforts for self-representation on an international scale. This is most forcefully illustrated by the rise of the Arctic Council as a political force. In 2013, the organizational body held a forum in Kiruna attended by the likes of John Kerry and Swedish foreign minister Carl Bildt. (The latter later penned an op-ed for the New York Times on the council’s geopolitical significance.)

Barrow, Alaska

“Barrow is the perfect starting point to understanding the Arctic,” says architect Matthew Jull. “There are many social problems, but the Iñupiat have a stake in the North Slope, they have revenue from oil—that’s equitable.”

Courtesy Matthew Jull

Even with these advancements, indigenous groups such as the Inuit continue to exist in the public imagination as victims who have endured a series of crushing defeats. That much cannot be denied, but neither can their agency. “Inuit are the only people to go from the Stone Age to the Digital Age in a single generation,” the celebrated Inuit filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk has said. “These are an incredibly modern people because they are able to occupy two worlds,” echoes White. “Architecture has always failed in being as inventive as these people have in adapting to the modern world on their own terms.”

Many young architects are pursuing inclusive design methods that don’t discount the indigenous perspective, but actively engage it. Community-solicited design, however, has long been part and parcel of any architecture that claims to be both “democratic” and “empowering.” But this type of engagement can amount to mere surface treatment, an altruistic gloss applied to an otherwise formally invested project. Architects who want to work in the North should think twice before making that commitment, says Jull. “Planners and architects go to the Arctic, they stay there for a few years, and then they bounce.” What results is “this fragmented development, and the ideas don’t gel, they don’t crystallize into coherent plans.” The goal, it then seems, is to bring about the rise of the Inuit architect. “When you see things like music, art, film, and even performance art—these are mediums that indigenous people have excelled at using as a means of expression,” White says. ”But there are very few indigenous architects; I can’t even count them, there are so few.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025