August 10, 2022

Contemporary Quilters Are Piecing Together a New Era of the American Craft

Like most folks with Appalachian roots, I’ve met many quilts that have seen some stuff, that have lived entire lives long before I wrapped myself in their cozy patchwork. Recently, my mom texted me saying she’d found a box of my great-grandma Leila’s quilt blocks in my aunt’s basement, enough to make a full-size blanket: “Do you want me to mail them to you so you can finish the quilt? If not, we’re going to toss them.”

Although I never knew my namesake personally, I knew she was a real mountain woman. I also knew that since I had been quilting for only a few months, I was nowhere near the level of skill my great-grandma had applied to this particular stack of 1950s-era bow tie–pattern blocks. The pattern, which originated in the 1880s, is sometimes referred to as a more “masculine” motif, a design for quilts meant to be gifted to men and boys. More popular folklore, however, suggests that the pattern was originally used throughout the Underground Railroad—bow tie quilts hung or laid out on porches informed formerly enslaved people that they should change into more formal attire to blend in better.

Whatever the story of the blocks, of course I wanted them. I wanted to be able to carry on that conversation and connection with my ancestors and form my own story with these mundane squares of fabric. Perhaps most importantly, I certainly didn’t want to see them thrown out, where they would take decades to decompose. I might not ever be able to know what my great-grandma Leila’s intentions were with the quilt, whom she was making it for, or why she never finished it, but I could do something to keep those old scraps from entering the landfill.

My experience is not unique. And it wasn’t unique for my great-grandma either. The pile of blocks I inherited was obviously constructed out of recycled decorative feed sacks—everyday textiles that she would have had just lying around. This was a very common practice throughout the Southern United States in the 1940s and 1950s. It’s this ingenuity that has not only become a hallmark of the American quilt but in a way made the quilt an apt metaphor for many of the myths of what it means to be “American”—to piece together disparate parts, to layer different cultures and time frames, to “build something out of nothing.”

Today, artists and designers continue to lean into quilting’s resourceful roots. Sure, it might involve upcycling vintage feed sacks using a traditional pattern, but it also looks like saving abandoned quilts from yard sales, or even scavenging thrift-store dollar racks for unique fabrics that already exist, rather than buying yards of new material. One way contemporary designers are rethinking the ecological footprint of quilting is by transforming old quilts into clothing.

Made apparent by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Costume Institute’s latest exhibition In America: A Lexicon of Fashion, quilt clothes aren’t exactly a new concept. A section of the show titled “Nostalgia” features a sweater-and-skirt ensemble from Ralph Lauren’s Autumn/Winter 1982 collection that is crafted out of antique patchwork quilts and references 19th-century needlework samplers.

Popular clothing brands regularly market patchwork-inspired clothing, and even outside of fashion, contract textile manufacturers are playing up the aesthetic through collections such as HBF Textiles’ solid-tone commercial upholstery collection Ms. Quilty (2019) or KnollTextiles’ patchwork Homage textile, part of its Heritage collection launched this year at NeoCon. But as many contemporary makers will tell you, quilt clothing is about more than just a sentimental longing for the past—if anything, it is a form of stewardship.

In 2018, Oregon-based sewist Taylor Nelander made her first quilt jacket after spending two years reselling vintage, hand-mended, and “reworked” clothing online. It wasn’t until she was job searching mid-pandemic that the prospect of turning quilts into clothing could become a business model.

Nelander explains that she sources most of her material from Goodwill bins, and many of the quilts she repurposes have imperfections like stains, tears, or burn holes. “Eighty percent of [quilts] that I get would not exist if I wasn’t re-creating them into something that people are going to wear,” she explains. Nelander has also purchased quilts just to find an older quilt functioning as a middle batting layer. She says, “It’s funny and almost ironic. It comes full circle.”

Yet early last year, Nelander’s studio, Softpaw Vintage, was one of a handful of small businesses targeted in a viral YouTube video titled “Quilt Clothes Must Die,” in which Mary Fons, writer and quilt historian, vehemently calls for artists and fashion designers to “stop cutting up quilts to make clothes.” While Fons’s argument gets buried in the insults, name-calling, and general air of hostility portrayed in the video, she has a point: All handmade quilts are one-of-a-kind. With that in mind, Nelander agrees that it is sound advice that novice sewers feel comfortable in their craft before attempting to cut up an heirloom quilt for a new DIY project. But at the same time, Fons’s video misses the mark on the bigger picture: Quilts have been battered, beaten, torn up, added onto, patched, reused, and transformed throughout the entire history of the craft. Aside from the influx of tutorials and imagery on social media platforms like Instagram and Pinterest, has much really changed?

While Brooklyn-based quilter Zak Foster, perhaps best known as the craftsman behind A$AP Rocky’s 2021 Met Gala look, doesn’t make new clothing from old quilts, he does know a thing or two about making new quilts from old clothing. “The more I fell in love with quilting, the less I could stomach the idea that something I loved so much would also be causing some kind of harm to our [planet],” Foster explains. “Working with repurposed material forces one down a certain creative path, because you have to work around the material’s own background, stories, and imperfections. Ecologically and creatively, it keeps me on my toes.”

“Quilting is the original zero-waste craft because it started with scraps from garment making,” Foster notes. “But we are producing way more fabric than at any point in human history, and [for artists and individuals] zero waste is not a solution. The solution is less production. But in this moment, we are teeming with fabric, so we’ve got to figure out something to do with it in the here and now. My answer to that is quilts.”

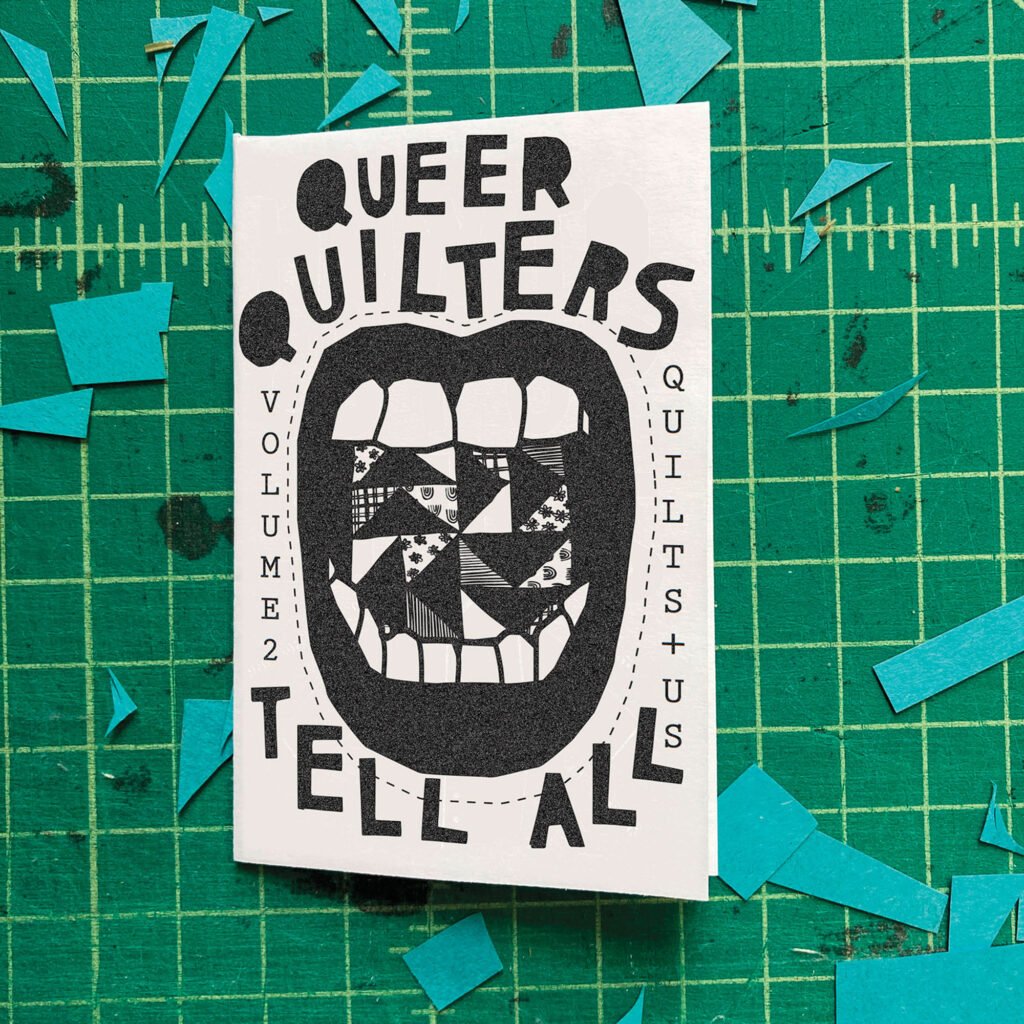

For Foster, quilts aren’t only a way of extending the life of the materials that form them, but also act as extensions of the makers’ traditions, practices, and personal narratives. From the Underground Railroad to the AIDS Memorial Quilt to the quilting bee, historically, quilts have served as a platform for storytelling, giving voice to those who might otherwise be silenced. Building on this lineage in a series of four zines titled Queer Quilters Tell All, Foster teamed up with Chicago-based quilter Grace Rother to document the experiences queer quilters have had by using quilts as vehicles for change.

A contributor from Alabama wrote in one of the zines: “I think that queerness is often about taking what is presented and reassembling it into something that feels like an authentic, meaningful identity. I approach quilting exactly the same way.”

In fact, many quilters piecing together a new era of quilt-making identify as queer. In using textiles to explore their identities, narratives, and politics, their craft transcends what has historically been considered domestic “women’s work.” But the long history of quilting is full of examples where the craft was used to build community, raise money for mutual aid funds, memorialize, and rethink life under late capitalism.

One particular way Rother has moved beyond herself via her practice is through her Abolition Quilting Bee, a virtual project completed in 2020 in which nearly 120 people across North America submitted 12-by-12-inch quilt blocks that reflect on a future without prisons or police. Three quilts in total were completed and raffled off to raise over $12,000 for Assata’s Daughters, a queer, Black woman–led youth organization based in Chicago.

“I source all of my fabrics secondhand from friends, family, fellow makers, thrift stores, and garage sales. So while each quilt is a composition of shape and color, it is also an archive of the various communities that I’m part of,” Rother explains. “If you think about it, it’s a pretty traditional way of making quilts. It feels as though I’m writing a new chapter in a long story.”

Above all, quilts tell stories. Whether one is curling up under a blanket in the winter or donning one for the Met Gala, each quilt’s narrative is constantly evolving, with layers of meaning added by each person or place it touches. In a culture and climate where many things aren’t made to last, the act of mending, transforming, or creating something entirely new out of repurposed fabrics feels like a nurturing hug. To borrow words from Rother: “Quilts invite us to be vulnerable—to lie down, to dream, to rest. We’re living in a tough time right now, and I think it’s these gentle invitations to dream that will see us through.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

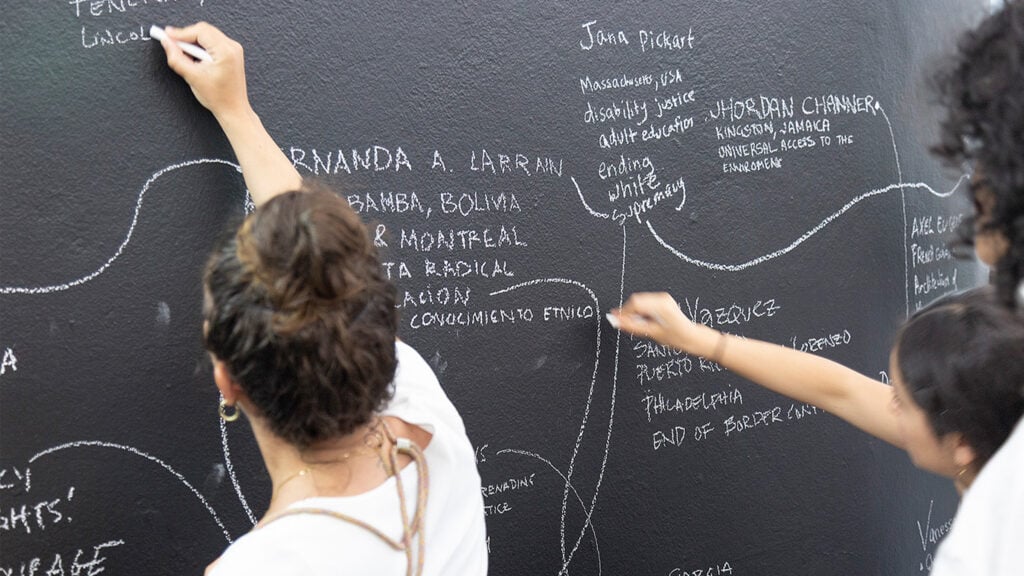

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.