March 14, 2019

Looking Back at the Destruction of Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, 30 Years Later

In an excerpt from the book Conversations about Sculpture, art historian and critic Hal Foster discusses the highly politicized battle with Richard Serra and Clara Weyergraf-Serra.

The following conversation is excerpted from Conversations about Sculpture from Yale University Press; the introductory paragraph was written by Amy Canonico, associate editor for art and architecture at Yale University Press.

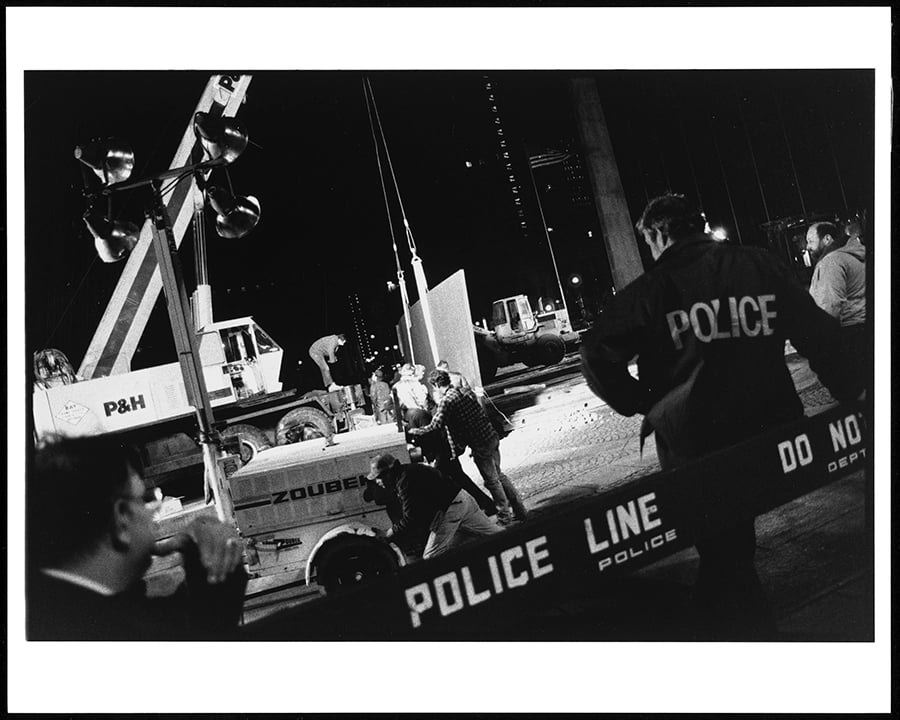

March 15 is the 30-year anniversary of the destruction of Tilted Arc, a site-specific work by the sculptor Richard Serra that was commissioned by the General Services Administration (GSA) for Federal Plaza in lower Manhattan. The 120-foot long steel sculpture stirred controversy shortly after its installation in 1981, with critics claiming it disrupted the plaza. Following an aggressive campaign for its removal (led by the GSA itself), public hearings, and lawsuits, Tilted Arc was removed from the plaza in 1989 and—as a work conceived in response to and inextricably linked to this particular site—effectively destroyed. In the recently published book Conversations about Sculpture, Richard Serra and Clara Weyergraf-Serra revisit the controversy in conversation with art historian and critic Hal Foster.

Hal Foster: The attack on Tilted Arc was an early salvo in a new cultural politics; it was part of the culture wars of the Reagan years.

Richard Serra: During the hearing about Tilted Arc, Edward Re, who was chief judge of the Court of International Trade, went so far as to say the work was causing a rat problem. That’s a fascist tactic. A security inspector testified that the sculpture could be weaponized as a blast wall—that, if you put a bomb in front of it, it could blow up the building. Any claim that could be used to subvert the work, no matter how outrageous, was used.

HF: I remember those statements. They presented the public as a mob to be watched and Tilted Arc as a wall that hid enemies of the state from government cameras. There was a tenor to the testimony that was paranoid.

Clara Weyergraf-Serra: You’re right: it was the beginning of a different kind of cultural politics. And Richard’s was the case they used to rewrite the guidelines—not only of public art commissions but more generally, too.

HF: With Donald Trump the culture wars are back with a vengeance. Not to romanticize Jackie Kennedy and Joan Mondale as patrons, but there was a dramatic change under Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush (and Bill Clinton didn’t do much to alter the situation—he was a populist too). Ed Meese was more a morality czar than an attorney general, and William Bennett, who was head of the National Endowment for the Humanities, essentially wanted to get rid of his own agency (of course that’s also back with Trump). Tilted Arc was used as a pretext to cut federal support for the arts. If the government can destroy one of its own commissions, that’s a good baseline from which to operate.

RS: Senator Jacob Javits, for whom the plaza was named, came out in support of Tilted Arc. He wanted it to be retained in the plaza, but they completely dismissed him.

HF: Re was against the sculpture from the start, but it was only in early 1985—when William Diamond took over the regional office of the General Services Administration, which had commissioned the sculpture in the first place—that things really went south.

CW-S: Yes, once Diamond entered the picture, the agenda was clear.

HF: Did he come with a brief?

RS: My hunch is that he came with an assignment, yes.

HF: But then the government, let alone the GSA, didn’t come out of it well.

RS: We don’t know the consequences at that level. Certainly the controversy split the art world.

HF: Many people in the art world testified on behalf of the piece, myself included. The great majority of the 180 people who spoke at the hearing in March 1985 supported the sculpture. How was it split?

RS: Many people in the art world came out for the piece, but the populist culture that surrounded the art world was totally against it. Grace Glueck led the charge in the New York Times, and others wrote attacks in other papers. The preponderance of articles was very negative; it became a media frenzy. And then there were the people who harangued me in the street.

CW-S: Richard received death threats over the phone. I went to the police because I was so spooked.

RS: Remember the photograph of the Vietcong being shot in the head by the South Vietnamese police chief? They took that photograph, wrote “Kill Serra” under it, and plastered it all over downtown. That came from artists.

HF: Was the position against the piece coherent?

RS: They said the sculpture blocked the view from the Federal Plaza. I don’t know what they wanted to look at.

HF: That came from people within the building. What about the populist part of the art world?

RS: Some took up the same battle cry.

HF: It was unfortunate that the controversy pitted people in support of the sculpture against people who wanted an open plaza for tables and benches. Douglas Crimp pointed out that was an artificial opposition, one that was manipulated by critics of the piece.

CW-S: There was talk about benches for people to sit down and have lunch on, and also talk about the fountain, which had been nonfunctional for years.

HF: I don’t remember the plaza being much used; people tended to hurry across it. But then it wasn’t exactly a “leftover” site either, in your sense of the term, like the rotary outside the Holland Tunnel. Did you have any inkling that the sculpture and the site would become so charged?

RS: Not before the legal battle.

CW-S: That battle dragged on for years, and at that time we didn’t have much money. Our first lawyer, Gus Harrow, was determined to win the case, but, sadly, he got cancer, so we turned to Jay Topkis, who was one of the main litigators at the law firm Paul, Weiss. Jay said, “I’ll take this case, and I’ll take it pro bono. I’ll write the best briefs, and I’ll do whatever’s in my power, but you’re not going to win.” He put a tremendous amount of work into it, along with an assistant attorney, Leslie Cornfeld, whom I’ll always remember. But from the outset Jay said, “I wish you’d come to me when you decided to bring legal action against the government, because I would’ve told you then, in no uncertain terms, you don’t have a chance.”

HF: So why was Gus Harrow gung-ho?

CW-S: He was the lawyer in the Mark Rothko case, which he won. Gus was a one-man office, and he really believed in the cause. But believing in the cause isn’t the same as winning the battle.

HF: What were the legal consequences? Did Topkis want to make as strong a case as possible in order to set a legal model, if not an actual precedent?

CW-S: Yes. Jay thought that, since Richard had started the process and we were so deep into it, it should be concluded in a way that would at least serve as an historical example.

HF: And if you pulled out, that wouldn’t be so.

CW-S: We never contemplated dropping the case.

HF: What were the consequences for you personally and for your work?

RS: The personal consequences were agonizing, daily, and continuous.

HF: Were you able to work otherwise?

RS: I continued to work, but the case consumed a tremendous amount of time and energy.

HF: Did the world divide for you into two?

RS: You mean those against and those for? I didn’t see it that way. I thought it was most of the art world against almost all of the media, and the people who knew nothing about art were influenced by the propaganda of the government repeated by the press.

CW-S: Richard continued to work. He did more shows with the Castelli Gallery and more pieces in Europe, but every discussion of his sculpture started with a reference to Tilted Arc.

RS: It was an albatross that wouldn’t go away. Even twenty years later people would bring it up. It was the first thing people wanted to talk about.

HF: Did it prompt collectors and curators to back away from you?

RS: I certainly wasn’t getting commissions in the States. On the other hand, as Clara says, I was working a lot in Europe.

CW-S: The tide only turned with the show at MoMA that William Rubin did.

HF: The retrospective in 1986? But the Tilted Arc controversy was still going on.

CW-S: Yes. Douglas Crimp wrote an essay for the MoMA catalogue about Tilted Arc and site-specificity, which Rubin didn’t want to publish.

RS: But he did publish it in the end.

CW-S: Only because you threatened to cancel the show.

HF: It’s extraordinary that there’d be an attack from the government at the same time as a retrospective at MoMA. That highlights the cultural divide of the Reagan years.

RS: What surprised me was that the retrospective was received very well. I couldn’t have anticipated that.

HF: Given the controversy?

RS: Yes, and the fact that my work wasn’t well known in the States then. The reviews were good, and people turned out. That was really gratifying.

From Conversations about Sculpture by Richard Serra and Hal Foster; published by Yale University Press in November 2018. Reproduced by permission.

You may also enjoy “Despite Its Oft-Copied Look, the Sea Ranch Still Provides Rich Architectural and Social Lessons for Today.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025