April 11, 2017

Fearful of Being Seen as Neutral in Turbulent Times, Cultural Institutions Are Striking an Activist Stance

The internal responsibility for an institution to respond is equally met by the very real external pressures generated by what is going on in society.

In June 2015, at the start of an almost halcyon summer compared with our last, President Barack Obama described the slow pace of democratic change to comedian Marc Maron. “Sometimes the task of the government is to make incremental improvements or try to steer the ocean liner two degrees north or south so that ten years from now, we’re in a very different place than we were,” he said, suggesting that a 50-degree turn was unmanageable. Fast-forward through a vicious election season, an unnerving inauguration, and a hot rash of executive orders, and it feels like not only has the ocean liner turned 50 degrees, it’s capsized.

While individuals can take to the streets, the phone, or social networks to voice their political views on a furious host of contemporary issues, cultural institutions are like ocean liners, stately and slow to turn. (Some are careful not to upset their donors or nonprofit status by taking a stance.) Increasingly, though, museums, journals, and universities—as agents of curators, editors, and faculty—have quickened their pace. Rather than pledging allegiance to the new administration (ahem, AIA), these organizations are making super-relevant programming that sheds light on the complexity of worldwide political, social, and economic issues.

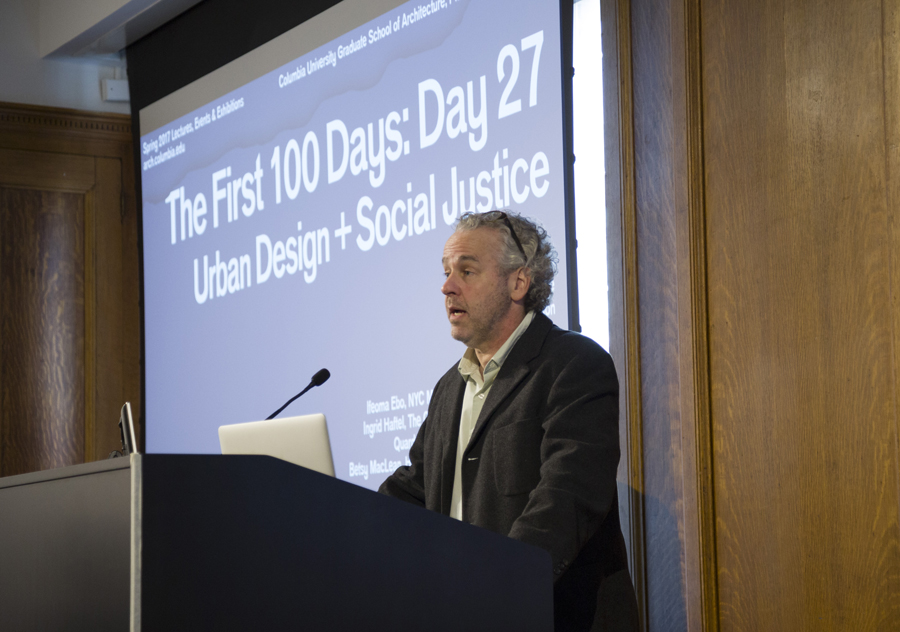

Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP) produced perhaps the most rapid response with a conversation series, “The First 100 Days,” which kicked off on January 20 with a live stream of the presidential inauguration. Day 27: architecture and grassroots organizing. Day 64: reflections on the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

For dean Amale Andraos, these gatherings stress the school’s commitment to a free exchange of ideas—across the political spectrum and between academia and the world at large—as well as a means to expand understanding of architectural practice to include public engagement and direct action. Additionally, the Trump administration’s executive orders banning travel of citizens from a slew of predominantly Muslim nations affect GSAPP students and faculty, as they do those at most universities. “The question is not so much whether schools should address politics, but whether they have a responsibility toward truth and the upholding of values,” Andraos says.

“Do we have a point of view? Yes, we are not neutral,” says Hammer Museum director Ann Philbin, defending the idea that an arts institution can take a position on pressing issues. “Do we have pushback from people about that? Sometimes, but they are far outweighed by the people that express gratitude for our programs.” The museum regularly features exhibitions and events around feminism, racism, and xenophobia. Now on view is a retrospective on artist and activist Jimmie Durham. Programming addressing Native American themes will run parallel to the show—an undertaking that has been particularly poignant and disturbingly apt since the Standing Rock protest camp in North Dakota was unceremoniously cleared.

Institutional timeliness, then, is not only about reaction but also about recalibrating approaches. The Hammer held a public gathering in early February to discuss organizing and taking action in response to the new administration. It featured leaders from Planned Parenthood, the ACLU, and the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights of Los Angeles. One thousand four hundred people RSVP’d. The organizers had expected 200.

The current political climate clearly amplifies national issues that were already in play. For example, New Cities, Future Ruins (NCFR) may have convened its initial event in Dallas just days after November 8, but the impulse undergirding the ambitious undertaking, which included gallery exhibitions, lectures, performances, panels, and site-specific installations, is hardly new. Formed through a partnership between SMU Meadows School for the Arts, ASU Gammage, and the UTEP Rubin Center for the Visual Arts, the multiyear initiative is based on themes that focus on the social and environmental crises in the western Sun Belt—evergreens of a dystopic sort for the region.

Yet artistic director Gavin Kroeber couldn’t have anticipated just how prescient NCFR’s examination of migration, borders, and climate change would seem in light of the election. “In our central geography, meaning has already changed,” he says. “Demographically, the region is shifting away from the right. Still, changes in immigration policy are going to land in the border states—a hammer may come down.”

The magnification of a local condition into a national conversation hangs over a city like St. Louis, which is still dealing with the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson and subsequent protests and riots. While those events sparked the Black Lives Matter movement, it is a place in need of psychic and physical healing.

Working with the Pulitzer Arts Foundation and Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, this summer artists Amanda Williams and Andres L. Hernandez will embark on A Way, Away (Listen While I Say). The project and aligned public programming are part of PXSTL, the foundation’s design-build initiative, but instead of creating a new pavilion, the pair will choreograph the demolition of a building and return the site to landscape. “What ways of thinking about the simultaneous demise and rebirth of the city can be stimulated through our project?” asks Hernandez, stressing the history of urban renewal and the labor necessary to rebuild an equitable and diverse place.

But tackling the hypercontemporary can be awkward, even when well-intentioned. There are questions of legibility and audience expectations. MoMA’s exhibition Insecurities: Tracing Displacement and Shelter closed two days after the inauguration. Focused on refugees, border security apparatuses, and emergency housing, as told through research, objects, and images, the show took critical heat for not offering up enough design solutions to crises around the globe. But architecture and design associate curator Sean Anderson says that wasn’t the point. “I wanted to use architecture in a discursive way rather than an answer unto itself,” he says.

Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA) director Mirko Zardini also takes issue with quick-solutionism—the scale and range of issues facing contemporary society, not to mention contemporary architecture, exceed the conventional purview of design. As with the Hammer Museum, CCA’s curatorial mandate is capacious enough to include and combine elements from many fields. That breadth was, up until recently, on view in Montreal in It’s All Happening So Fast: A Counter-History of the Modern Canadian Environment. Timed to coincide with Canada’s 150th anniversary, the exhibition is a call to action around climate change. It sits at the intersection of an increasingly impotent environmental movement and corporatized exploitation of Canada’s natural resources.

In short, Zardini argues for new kinds of engagement, new discourses, new platforms—a claim that comes from his belief that institutions bear an intellectual, moral, and ethical responsibility to address current societal questions. The internal responsibility for an institution to respond is equally met by the very real external pressures generated by what is going on in society. “It is very important to rethink the cultural and political way we frame the problems today,” he says. “So it is not enough to produce social housing; we have to think about how we conceive of the problem. We have to question the very idea of building. Architecture cannot be content to present a general solution. You have to take a position.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025