September 25, 2018

In a New Book, Alexandra Lange Explores the Design of Childhood

The critic extracts the cultural significance of toys, furniture, and environments designed for kids—and in the process, examines childhood itself.

Childhood is replete with children’s stuff, as any parent can testify, and many adults who may never before have given a stray thought to the subject of design become surprisingly passionate about it once their progeny are involved. Yet despite its ability to provoke powerful feelings, design for children doesn’t routinely receive the same thoughtful public analysis that adult-centric design and architecture do, which is one reason why the arrival of Alexandra Lange’s book, The Design of Childhood: How the Material World Shapes Independent Kids (Bloomsbury) is so welcome.

The Design of Childhood is notable not only for its ambition—mapping and giving historical context to the spatial frontiers of childhood is indeed no baby task—but for its exemplary hold on the fundamental if unromantic truth that children are a community who have never enjoyed much, if any, agency over the way their world is formed for them. Children, however, are not Lange’s primary subject here. Her training in design and architecture—she was a recent Loeb Fellow at the Harvard Graduate School of Design—as well as her prolific writing on the history and development of objects and environments associated with domestic life, have made her uniquely qualified to tackle her real topic, which is not children per se but the ever-changing adult idea of what a child is, and how that idea is expressed in children’s environments.

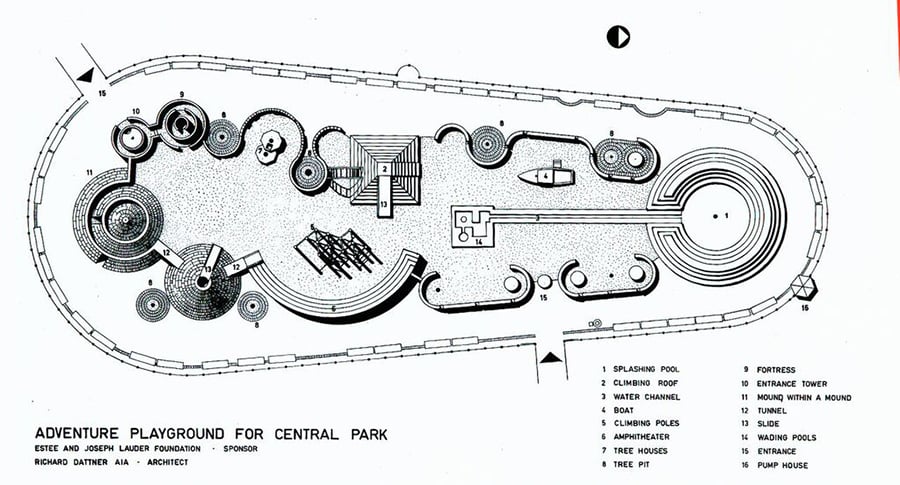

As a well-known architecture and design journalist, Lange has blazed an admirable trail in a terrain dominated by male writers, and her formidable skills as both a researcher and synthesizer-of-facts are on display here. Unsurprisingly, her book is also beautifully structured, imitating the perspective of a growing child itself: Beginning with an initial chapter on “Blocks,” Lange increasingly enlarges her perspective over four successive chapters, titled “House,” “School,” “Playground,” and “City.” With each section, Lange explores how and why these realms have been configured the way they have been—and that is, nearly always, by adults and for children.

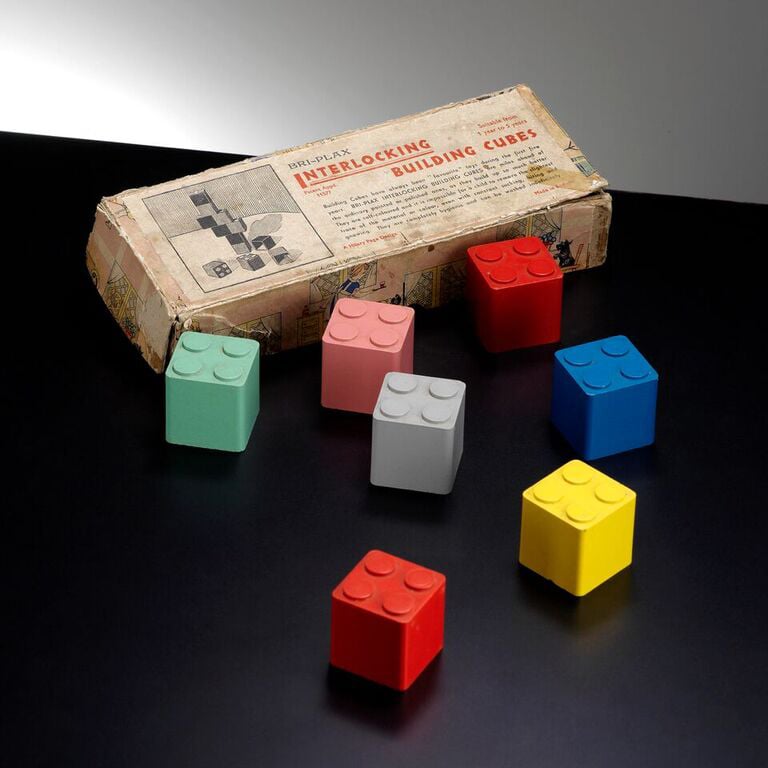

In “Blocks,” for instance, Lange traces the dramatic history of the now-ubiquitous LEGO block from its humble origins as an “interlocking building cube.” The near-epic tale, which includes a lawsuit as well as the suicide of a LEGO-prototype-maker, highlights the struggle toymakers had in getting parents to view plastic, rather than wood, as an acceptable play material. Taking readers further down the historical trail of toy evolution, Lange examines how toys perceived as having creative and educational value came to be prized over those thought to be either lacking such positive properties, or worse, espousing negative ones, such as violence. Lange traces the development of this Good Toy vs. Bad Toy perspective to the emergence of mass-produced toys in the late 18th century, and insightfully notes that though the judgments have shifted over time, the split itself remains unchanged. Keenly, she spots the Good/Bad dichotomy in the hugely popular contemporary video game, Minecraft, and its two player modes: “Creative” and “Survival.”

Lange shows her commitment to bringing all types of design decisions to light, even when the reasons behind them aren’t pretty. In her chapter on “School,” she explores the 3,500 Rosenwald Schools built for African-American children in the rural South between 1917 and 1932—facilities, Lange points out, that were “specifically designed to be lesser in appearance than white schools.” She is also forthright in noting that the designs of the homes she discusses in her chapter on “House” need to be seen within the broader context of the fact that, in 1960, “almost 31 million homes were owned by whites, compared with approximately two million owned by nonwhites.”

The Design of Childhood additionally enriches its investigation by opening each chapter with a quote from a children’s book that’s relevant to the chapter at hand. This move emphasizes the degree to which ideas about children and their environments are literally always in play—in architecture and design as well as in literature—and further underscores that ideas about childhood are, like children, always under development. (Century of the Child: Growing By Design, 1900–2000, MoMA’s excellent exhibition, also brought some attention to this idea in 2012.)

Lange occasionally ventures into more personal territory, including anecdotes from her own childhood, and from her experiences as a mother of two. These asides are appealing in the way they round out her scholarly work, offering readers the acknowledgement that it’s nearly impossible to divorce one’s own childhood experiences, as well as one’s experience as a parent, from understanding design for children. In detailing the origins of the Tripp Trapp chair, for example—the well-known, and famously adjustable, Scandinavian wooden kid seat—she reveals that she had bought her older son one of these chairs when he was two, thinking he would hand it down to his sister four years later. “Nine years on,” she writes, “he is still using his (orange), and we had to buy a second for her (plum).” She then adds, in a wry bit of mental reframing surely familiar to many parents: “I had to consider them an investment.”

Adult ideas about children and how they should grow up are, and probably always will be, the primary driver of how children are required to inhabit our adult world—at least until the day comes when we adults begin inhabiting a world run by children. Until that unlikely moment, we are lucky to have a writer like Lange putting children’s environments into context, to help us see the responsibility we bear, and to make better decisions about what and how we build for children in the future. This is also why her book is an important addition to the library of any adult—parent or not—who cares about those ideas.

You may also enjoy “At Rockwell Group’s New Blue School, ‘the Space Is Almost the Third Teacher.'”