March 8, 2024

How Dune and Poor Things Rely on Architecture History

Science fiction is everywhere. What once were visions solely to be found in mass-market paperbacks, now populate our everyday. After all, the opening scene in Greta Gerwig’s 2023 blockbuster Barbie wouldn’t have been instantly recognizable to so many without the widespread cultural impact of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. From students crafting spaces in the Metaverse to world-renowned firm Zaha Hadid Architects’ recently completed Science Fiction Museum in Chengdu, China—it’s clear that designers have always, and will continue to be, fascinated by visions of the future.

“Science fiction describes a way of thinking and perceiving, a toolbox of methods for conceptualizing, intervening in, and living through rapid and widespread socio-technical change,” explains media and cultural studies scholar Sherryl Vint in her book, Science Fiction (MIT Press, 2021). “The struggle to shape the future is not only material: it is equally affective and imaginative.” It should come as no surprise that science fiction, with its ability to envision the future and explore alternative realities, has significantly influenced architectural thinking and practice. But recent speculative films like Dune and Poor Things have come full circle, drawing upon real avant-garde architecture and arcane historical references to depict buildings and places of another time and reality.

Collaged Worlds: The Steampunk Universe of Poor Things

In Yorgos Lanthimos’s 2023 film Poor Things, for example, production designers James Price and Shona Heath collaged worlds together, taking viewers on an architectural tour of fin de siècle Europe as seen through a steampunk lens. Airships, motorized carriages, and other fantastic contraptions populate alternative visions of London, Lisbon, Alexandria, and Paris. Most of the intricately designed sets were built in Budapest and were constructed on vast soundstages (the Lisbon set in particular was a marvelous feat production design, featuring full-scale steel-frame buildings, cobblestone streets, and a 60-foot-high painted backdrop.)

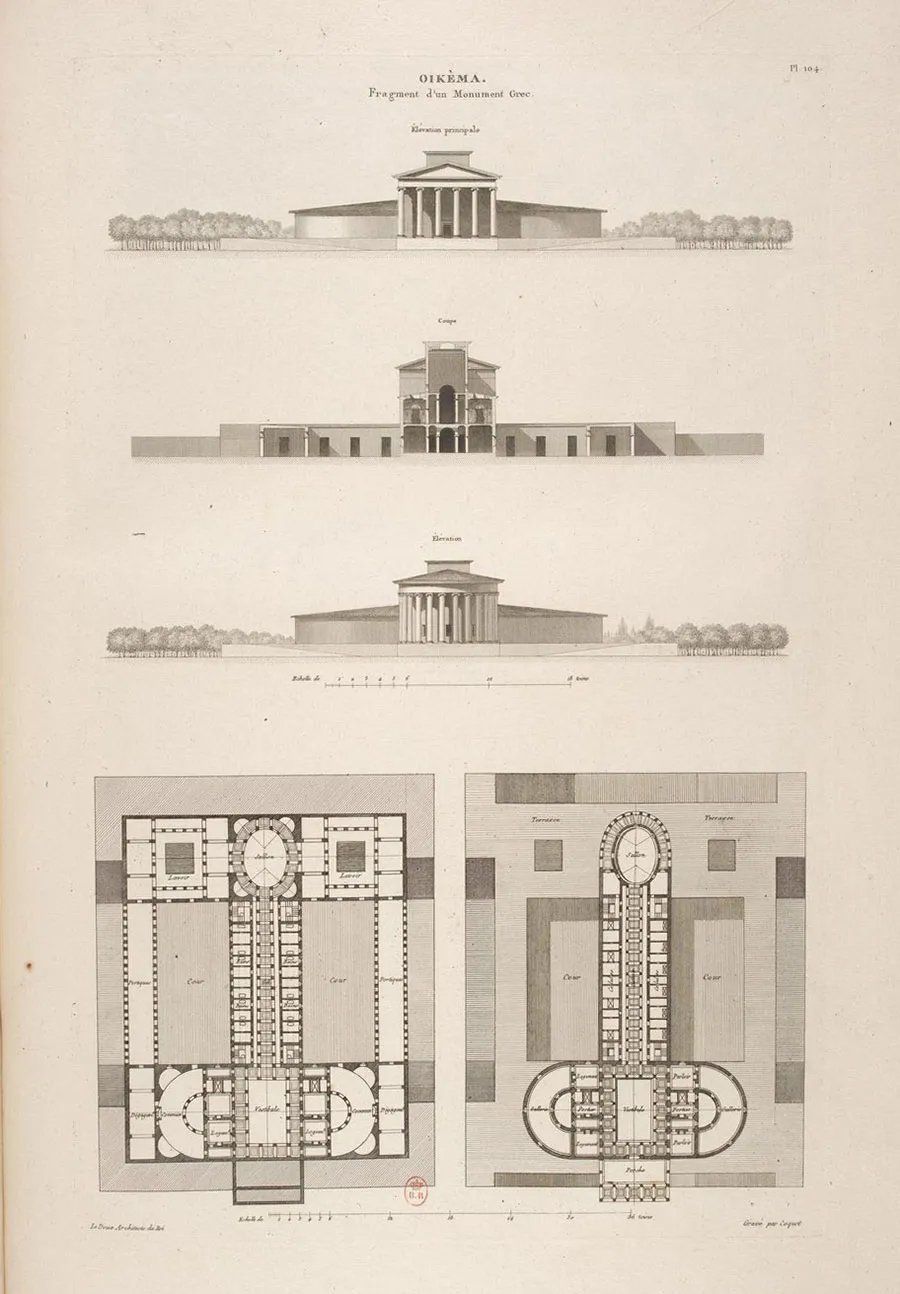

The retro-futuristic, Frankenstein-esque film is gorgeously grotesque, and the creative team drew from sources ranging from the eclectic architecture of John Soane to the paintings of Egon Schiele. The Baroque interiors of the film’s brothel evoke Claude Nicolas Ledoux‘s phallic fantasies for his French neo-classical pleasure palaces combined with Antoni Gaudi’s Modernisme and the Secessionists’ sinuous decoration. The designers also cite architect Ricardo Bofill’s postmodern megastructure Espaces d’Abraxas as a point of inspiration. The designer’s interest in Bofill may not be the most obvious visual reference, but its inclusion points to one of dystopian fiction’s most beloved motifs: the megastructure.

Embattled Brutalism: The Design of Dune

Describing modernist megastructures—think Moshe Safde’s Habitat 67 and Renzo Piano’s Centre Pompidou—Aaron Betsky writes in his new book The Monster Leviathan: Anarchitecture, “…they only became symbols of a hopeful modernity in which technology would solve all our problems. Such dreams never lasted. Instead, the ultimate megastructure became the prison-like environment depicted in science fiction films.”

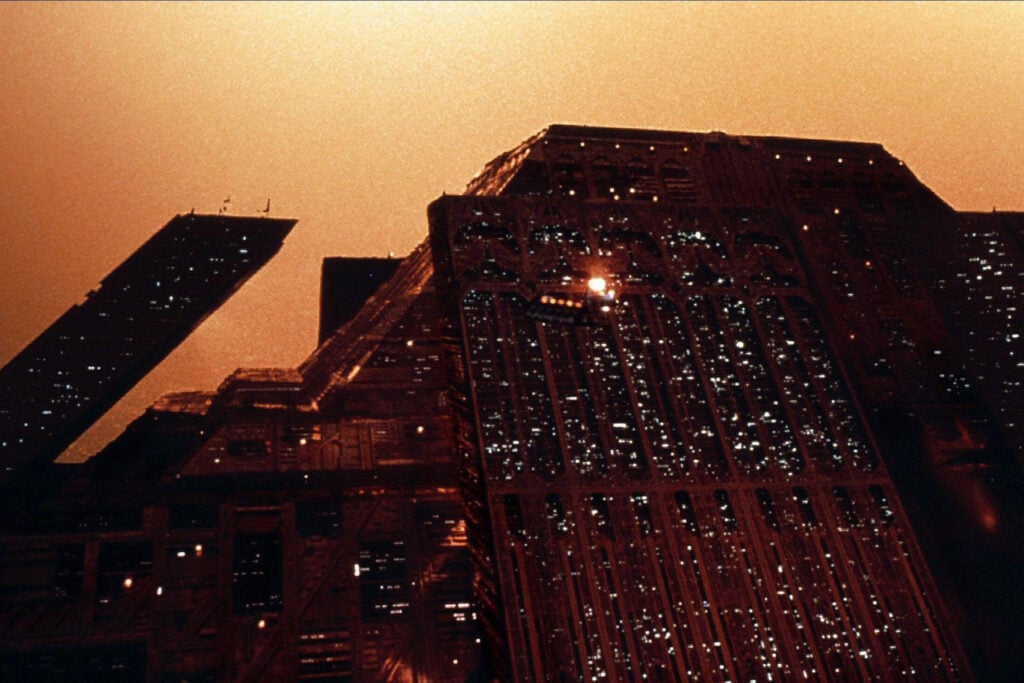

From the House Atreides’ fortress-like palace in Denis Villeneuve’s adaptations of Frank Herbert’s Dune, to the ominous Tyrell Corporation in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1983), the megastructures of science fiction undoubtedly reflect the goals and contradictions of the Modernist project. “The attempts to create an interpretive structure that fully traced the dissolution of reality is to me the central task of modernist architecture,” Betsky continues. “That this structure proved to be unstable, ephemeral, and uninhabitable—that it was, in fact, explosive itself—only reinforces its ambition to make modernity at home in architecture, and architecture at home in modernity.”

Betsky makes compelling connections between speculative fiction and Frank Lloyd Wright, through what he calls “anarchitecture” or, “a collection of images and proposals that do not quite live and breathe, but that haunt architecture. Neither utopian nor dystopian, they give force to architecture’s continual search for meaning.” The title of Betsky’s book is a reference to a seminal lecture Frank Lloyd Wright gave in Chicago in 1901 titled The Art and Craft of the Machine. “What Wright held onto, if only for a moment,” Betsky writes, “was the notion of an architecture that did not inhere in building but was evoked through words.”

Frank Lloyd Wright’s influence on the design industry as a whole goes without saying. The man notoriously designed everything in his buildings from the doorknobs to (sometimes) the clients’ outfits. But how his influence has infiltrated science fiction is less articulated.

The awe-inspiring buildings of Dune are filled with references to Wright. In the room in which Paul trains in the Atreides castle, Timothee Chalamet’s silhouette is highlighted by a massive arch window covered by a screen reminiscent of those in FLW’s Martin House. Elsewhere, Paul’s bedroom at the Arrakeen fortress (said to be the largest building in the history of humanity) features heavy concrete walls and varying ceiling heights that recall how Wright’s horizontal interiors utilize linear elements to convey a sense of open vs. closed. Production designer Patrice Vermette has cited other references that include WWII bunkers, ancient ziggurats, Brazilian Brutalism, and John Portman’s cascading terraces at San Francisco’s Hyatt Regency.

Cyberpunk and the Architecture of Techno-Modernity

Many of the architectural references in Villeneuve’s Dune can be found elsewhere in the science fiction canon, from Blade Runner (1982) to Westworld (2016). Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, an adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, also draws inspiration from Portman, notably, the opening act is set in his Bonaventure Hotel, an infamously disorientating icon of postmodernist corporate architecture. The film’s grim, cyberpunk vision of Los Angeles features several other iconic L.A. buildings, from the Bradbury Building to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis House.

Inspired by the Ennis House, Deckard’s apartment blends Mayan and Art Deco motifs, its boxy massing drawing on the languages of ancient ruins and the emerging visual language of 1980s computer design. The entity behind the film’s androids, the Tyrell Corporation, combines late modernist aesthetics with that of the English High-Tech movement, Kate Wagner tells 99 Percent Invisible in a 2017 article. “The building that immediately comes to mind upon looking at the Tyrell Corporation is the Pyramids, a complex of buildings in Indianapolis designed by Kevin Roche and constructed in 1972.”

Brave New Worlds: Learning From Science Fiction

Throughout the golden age of sci-fi in the 1960s and 1970s, series such as Star Trek and films like 2001: A Space Odyssey built their cinematic universes by incorporating both the popular and the more obscure designs of their time. “The films and television of the space age really solidified the aesthetics of ‘the future’ as it exists in the popular imagination,” says Eno Farley, devoted Trekkie and the brains behind the popular Instagram account @startrekdesign. In turn, the environments depicted in science fiction influenced countless “real-world” design decisions, pushing professionals towards greater experimentation and speculation of a more democratic design. The darker sci-fi of the 80s and 90s drew other architectural references—Brutalism and High-Tech—into this dialog, casting those megastructures in dystopian light. While the Star Trek and Star Wars films of the 2000s returned to asprirational midcentury forms and space age motifs, Dune and Poor Things use maximalist and full of layered (if sometimes arcane) references to depict complex and uncertain futures.

Studying the relationship between architecture and science fiction shows us that sci-fi isn’t just a genre, it’s a practice—a tool for rethinking our surroundings, from how we live with artificial intelligence to how we reflect on the catastrophic implications of climate change. Just as the dominant narrative of science fiction is to show us what it means to be human, the built environments found within these imaginative worlds can help us speculate on new forms of social structures and new ways of being.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Products

Behind the Fine Art and Science of Glazing

Architects today are thinking beyond the curtain wall, using glass to deliver high energy performance and better comfort in a variety of buildings.