September 20, 2022

Five Models of Work and Home

Moving forward, the relationship between work and home will not likely conform to some master narrative or a single model.

While the conditions of remote work are not new, the massive scale of this phenomenon during the pandemic was something of a revelation for millions of workers. Suddenly, many of our assumptions about the spatial requirements of modern work were turned upside down. This unprecedented test of new behaviors has served as a powerful reset for the world of workplace design, presenting architects and designers with the challenge and the opportunity to imagine new spatial vocabularies. And yet, anyone surveying the new products of NeoCon this past June would have been hard pressed to identify signs of any fundamental change in the world of contract furniture, raising the question: Has the industry returned from a two-year culture shock with an attitude of “business as usual” or are there new ideas in the product development pipeline that will help us make sense of our changed world—and changed industry—in the near future?

Designers, architects, urban planners, manufacturers, and organizations engage with these issues at different levels of scale, but all must think critically about how we understand “home” and “work” themselves, how each has changed— and how our hopes/desires for each have changed too—as a consequence of their being forcefully thrown together by the pandemic.

To start, let’s unpack a range of models from past and present to understand where “work from home” (WFH) has been.

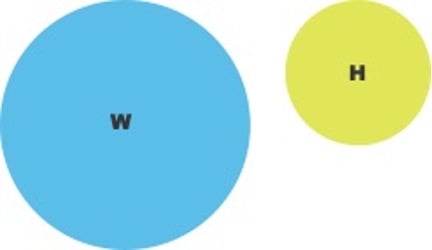

Industrial Model

Most American cities were built to support an industrial logic where there was a clear separation between work and home. This made perfect sense when the tools of production (factories) were centralized, so most cities were designed with a hub of industrial work in the center and rings of residential districts at the periphery. Workers commuted from a home zone to a central work zone.

Much of contemporary work still conforms to this older industrial logic, even as many economies have shifted to post-industrial conditions that are now based on decentralized (digital) tools of production that take advantage of a new network logic. This model has problems and inefficiencies, most of which are paid for by workers: prolonged commutes, time away from family, a continual sense of spatial displacement.

That said, there are also many clear benefits to this tradition: group cohesion and belonging, social connection, space designed for efficiency and collaboration, and a clear mental separations between work modes and home modes. This logic of separate locations has allowed the spatial vocabularies of each to remain relatively pure—at least in theory—with workspaces speaking a language of professionalism and efficiency and home spaces serving as expressions of domesticity, family, and leisure. Think scenes from Mad Men (complete with its dated gender ideologies about who works where).

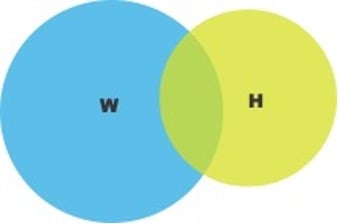

Network Model: Early Remote Work

Remote work is not new and has been steadily expanding since the 1990s, when new digital tools untethered some workers from the office desk. For the most part, workers and organizations continued to conform to a traditional model of co-located work at a centralized space, with occasional flexibility to work from home for those with the desire and the means to do so. Many have discovered that working from home (WFH) lends itself more to certain kinds of work or to particular phases of a project that require more individual focus. Around the turn of the century, books like Daniel Pink’s Free Agent Nation began touting the idea of working for yourself, especially using new network formats. These models of practice turned “employees” into consultants who operated with a new spatial freedom, often from home. New spatial choices were emerging, but before the pandemic they were the exception rather than the norm.

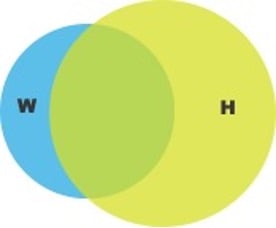

The Pandemic Model: Work from Home

This model emphasizes a change in proportion as home has become the primary space of production for many kinds of workers during the pandemic.

On a cultural level, COVID-19 has been a wide-scale radical experiment for new behaviors. Particularly in the early weeks of the pandemic, people were forced to think tactically about their daily lives in ways that were never required before. Whole populations had to research, solve problems, and design new ways of living. Even if these were unwelcome changes, the amount of collective creativity that played out in 2020 was impressive, as normal folks found ways to pivot into new patterns when their old ones were rendered impossible, if not dangerous.

Spatial needs are highly contextual. For many, the conditions of WFH were forced upon them and considered temporary. They found new ways to perform their jobs remotely with the tools they had, such as tables, computers, WIFI, maybe a new Zoom download. While these patterns were driven by difficult limitations and forced improvisation, they also unearthed some refreshing new possibilities for how we think about the spaces in our lives. Some previously default practices now seem obviously outdated, revealing worn-out assumptions about the spatial requirements of modern work. What’s more, the new lifestyles of WFH quickly took hold, like a genie that, in many cases, refused to go back in the bottle, as evidenced by the “great resignation.”

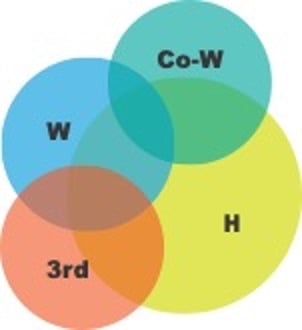

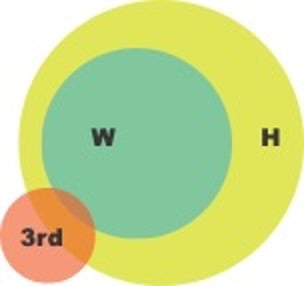

Hybrid Model

If historic changes require us to deconstruct and remix ideas of workplace and home, then it’s useful to consider the help of other spatial vocabularies in the mix. For example, co-working spaces, shared tenant amenities, and even public “third places” can help to support spatial choices and organizational flexibilities.

“Third Place” is a term used to describe a social setting separate from the usual social spaces of home and the workplace. This idea points to the growing presence of work-related activities in public spaces like parks, hotel lobbies, and cafes, which may serve less as an alternative to office or home, but rather a mediating space which can accommodate elements of both.

Buzzy terms like “hybrid work culture” have emerged to summarize the flexible spatial conditions of remote work, and to emphasize a shifting set of needs as workers and organizations sort through new priorities for workplace design. The flexibility of the hybrid model allows both organizations and workers to adapt to changing conditions but comes with tradeoffs. For example, managers may struggle to build organizational culture and workers who do come into the office may find it mostly empty.

Integrated, Mixed-Use Model

This model represents the full integration of the workplace into a residential space. The classic example would be the shophouse with a residential apartment above a street-level commercial space. This model can work well for independent consultants but could apply to various cottage industries as well. So far, this model may be limited by zoning restrictions, but new models of WFH suggest the need to rethink our cities to support coworking communities and the “third places” that might accompany them. This is an emerging model that needs more consideration as these spatial typologies begin to integrate into new plans for various developments and communities.

Moving forward, the relationship between work and home will not likely conform to some master narrative or a single model. The change our culture is undergoing leaves room for many new stories to evolve. Understanding these basic categories is a starting point to explore new spatial models and stories both for individual workers and the organizations they serve.

Read Part II of Work from Home Changes Both: Remixing Work and Home: How to Think About Hybridity

Scott Klinker is principal of Scott Klinker Design Studio and has been the 3D designer-in-residence at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan since 2001, where he oversees the graduate 3D design program. His practice strikes a balance between cultural research, industry projects and experiments, and working with design-driven clients like Herman Miller, Alessi, Steelcase, Landscape Forms, Burton Snowboards, and others.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

How the Furniture Industry is Stepping Up on Circularity

Responding to new studies on the environmental impact of furniture, manufacturers, dealers, and start-ups are accelerating their carbon and circularity initiatives.

Viewpoints

The 2024 Net Zero Conference Highlights the Importance of Collective Action

Last month, leading climate experts convened at the Anaheim Convention Center to reenvision the built environment for a net zero future.

Projects

McDonald’s Reimagines its Interiors through Radical Circular Design

A pilot program launching in McDonald’s France and Belgium aims to create sustainable interior renovations for the global fast-food brand