September 25, 2017

How Abstract Art Influenced Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architecture at the Guggenheim

Nonobjective art may have been a major factor in Wright’s design for the Guggenheim, according to a new Yale University Press book.

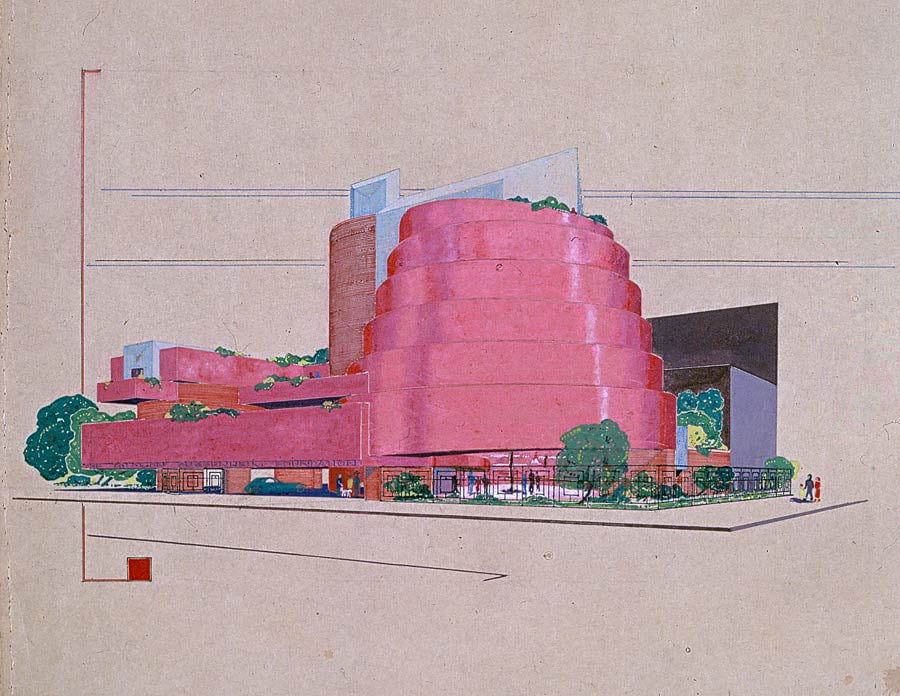

Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

In October 1959, when the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum opened the doors to its new building on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, it promptly became “the obligatory topic of every New York conversation,” noted the writer Italo Calvino. The last built work by Frank Lloyd Wright, who had died earlier that year at 91, was not showered with praise, as one might now expect, but pelted with criticism. Most of its detractors rallied behind one specific indictment: “Everyone claims that the architecture dominates the paintings and it is true,” explained Calvino, who, in his blithe acceptance of the museum as a place to go “primarily to see the architecture,” stood almost entirely alone.

Calvino’s remarks form the opening epigraph of The Guggenheim: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Iconoclastic Masterpiece, a new history of the building by Francesco Dal Co and the second installment of the Great Architects/Great Buildings series published by Yale University Press. In the spirit of the inaugural volume—an essay also by Dal Co on Paris’s Centre Pompidou—the historian sets out again to trace the circumstances that enabled the realization of a building so resistant to the orthodoxy hardening around it. Drawing from correspondence, theoretical discussions, technical analyses, and substantial previous scholarship, he illustrates the charged climate surrounding the genesis of the Guggenheim, condensing decades into a narrative of overlapping events to arrive at new interpretations of Wright’s masterpiece.

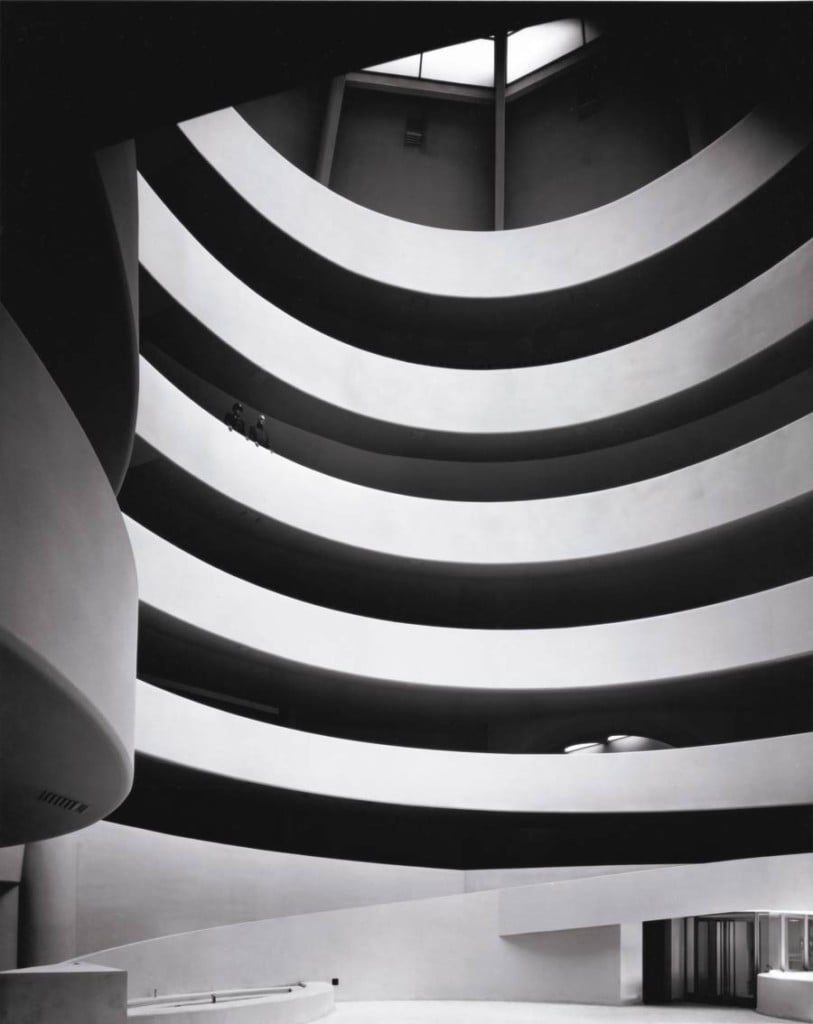

Dal Co begins by highlighting a well-documented episode. In December 1956, a cohort of 21 artists, including Willem de Kooning and Robert Motherwell, published a letter in the New York Times urging the Guggenheim Foundation to reconsider a formative aspect of its forthcoming museum: the use of natural light—streamed through the coiling skylight wrapped around the building’s hull—to illuminate the artworks. According to Dal Co, this public dispute did much to situate the Guggenheim within a long-standing conflict—the clash between the disciplines of art and architecture, as Calvino had observed. Moreover, the general perception of Wright as a brashly egotistical figure has abetted the reading of the museum as a self-glorifying monument, a final expression of Wright’s elevation of his own art at the expense of all others.

Yet sketches dating back to 1943, when Wright was formally commissioned, attest that, far from being an impetuous final lunge by an architect in his twilight, Wright’s spiraling art museum was a concept he spent almost a quarter of his career developing. For Dal Co, its 17-year time line is enough to suggest that Wright’s claims of having thoroughly considered the building’s function deserve more sympathy. To this end, Dal Co broadens the project’s historical scope, painting the Guggenheim as a culmination of ideas incubated over the course of Wright’s life, philosophies that he sought to synthesize with the aspirations of his clients.

One chapter of the investigation begins with the museum’s patron Solomon R. Guggenheim, whose late-blooming interest in collecting art linked up with the ambitions of the German émigré painter Hilla Rebay. Rebay’s devotion to nonobjective art—a movement whose chief practitioners included Wassily Kandinsky, Rudolf Bauer, and Rebay herself—not only greatly influenced Guggenheim’s collection but also prompted the businessman to entrust the foundation of his eponymous museum to his favorite art consultant. It was Rebay who dictated the architectural demands of the future Guggenheim Museum, making specifications for a structure illuminated with diffuse light and uninterrupted by stairs—to all of which Wright responded enthusiastically.

Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Crucially, the historian foregrounds a tangential development that likely accelerated the kinship between Rebay and Wright. In 1939, the Rockefeller-endorsed Museum of Modern Art relocated to a new building on West 53rd Street designed by Philip Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone. Dal Co suggests that this not only hastened the time line for the Guggenheim Museum but also provoked certain anxieties for its two main stewards: While Rebay opposed what she saw as MoMA’s increasingly corporate treatment of art, Wright took issue with the museum’s propagation of the International Style, which he saw as an obstruction to his vision of architectural Modernism. Wright and Rebay were thus allied in their commitment to developing an alternative to MoMA, both wielding the rhetoric of nonobjective art to counter the rising cultural monolith.

Among the most compelling aspects of Dal Co’s history is his interpretation of Wright’s design as a rigorous translation of the “nonobjective” ethos. Though Wright found the term inadequate, he empathized with its art, which, as Kandinsky theorized, “creates its own elements, without making use of any object whatsoever.” Dal Co proposes that Wright sought to give architectural expression to nonobjectivity, harnessing his expertise to conceive a museum building that “creates its own elements.”

To explore this hypothesis, the historian searches for patterns in the development of the Guggenheim’s design. He observes how, even as Wright and his clients were scouting possible locations for the museum—hovering around a sprawling park ground in the Bronx before considering several plots on the East Side of Manhattan—the architect did curiously little to change his initial concept, only tweaking and rearranging the same core elements. In fact, Wright’s scheme for a spiraling ramp crowned with a transparent cupola remained surprisingly intact over the years, even when Rebay began equivocating on this almost-literal interpretation of her stairless, light-filled “temple.” In Wright’s disregard for site specificity and obsessive reworking of the same forms, Dal Co sees the essentialist logic of nonobjectivity, suggesting that Wright was working toward “a volume that depended on its form alone rather than its traditional and symbolic meaning.”

As such, the Guggenheim isolates itself from its urban context, disavowing Manhattan with its thick bands of concrete. Its iconic spiral also refuses to signify any outside form. As Dal Co recounts, Wright incessantly revised it, smoothing out its once-polygonal plan, turning it upside down, and inverting its interior volume, eventually configuring it into an interpenetration of two oppositely oriented cones. With each permutation, he stripped the form of its allusions to earlier works—including Wright’s own ziggurat-inspired schemes and, as Dal Co reveals, a contemporaneous spiral-planned museum by his rival Le Corbusier—and achieved the dynamic helicoid space he saw as faithful to his patron’s wishes. Finally, Dal Co relates how Wright’s design generated the need for innovative construction processes, forcing the architect to make “ceaseless adjustments and well-camouflaged compromises” and consider every aspect of his design as he ushered it into reality.

Dal Co tends to emphasize the space between adjacent narratives, constructing his history with potent omissions as well as facts, occasionally letting quotes from Galileo, Erasmus, and others ring in his capacious chronicle. He builds up to a heady thesis, proposing that the Guggenheim contains a force of subversion even more profound than what meets the eye. Formless as it is, Dal Co’s claim resonates with a unique specificity, as several contemporary art institutions might look to Wright’s monument as a progenitor of their own freely contorting buildings. Importantly, the historian stresses the significance of time in shaping Wright’s final project. For one, the architect had an exceptionally long and fruitful career. But only over time, too, could Wright interrogate his own decisions, gradually distilling his vision into a building possessed of an indescribable charge—what one might call, as Dal Co indeed does, timelessness.

You may also enjoy “Aging and Demolished Frank Lloyd Wright Projects Prompt a New Look at Experimental Preservation.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025