May 16, 2019

How Two Getty Initiatives Are Saving Global Modernist Heritage

The Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative (CMAI) and Keeping It Modern grant are dedicated to supporting new methods and technologies for the conservation of Modernist buildings.

“Architecture is the will of the epoch translated into space,” Mies van der Rohe famously wrote in 1924, putting forth a case for Modernism. His argument, like many of the era, sought to break with the stodgy past and its artisanal techniques.

While the oft-quoted line couples buildings and culture, later in the same text Mies mandates timeliness over timelessness, suggesting that design is subject to the forces and flows of the current moment. The art of building, he mused, “can only be manifested in living tasks and in the medium of its epoch.”

But what happens when architecture is subject not to its own time but rather to the ravages of time? Materials age and uses obsolesce. Curtain wall gaskets wither. Laminates come unglued. Architectures designed to propel us into the future are thus welded to the past. The strategic upkeep of Modernist buildings is the key concern of two ongoing and sometimes dovetailing programs: the Getty Conservation Institute’s (GCI) Conserving Modern Architecture Initiative (CMAI) and the Getty Foundation’s Keeping It Modern grant.

“Modernism began a complete break from tradition—we see this in social and material reform,” explains Susan Macdonald, head of buildings and sites for the GCI. “Lots of technological development happened postwar: prefab, industrialization, the de-skilling of the building industry. But there were repercussions for those innovations and the speed of new construction.”

Founded in 1985, the GCI conducts a wide range of research and training, covering fine art and heritage sites from many historical periods. The CMAI, established in 2012, falls under that umbrella, applying conventional conservation tools to Modern architecture while developing specific methodologies to confront challenges specific to the 20th century. “Materials like plastics decayed more quickly than traditional materials,” Macdonald says. “And when materials like wood or stone were abandoned for aluminum or concrete, people didn’t always know how to best make a repair.”

To address these issues, Macdonald and Gail Ostergren compiled an extensive reference guide for modern architectural materials, Conserving Twentieth-Century Built Heritage: A Bibliography (2013). Sections dedicated to cladding, glazing, metals, and construction systems highlight the classics of kit-of-parts Modernism, the material culture of the International Style. But it is concrete—prefab, in situ, prestressed, post-stressed—that is the truly ubiquitous material of the period and the one most difficult to conserve.

Moisture and air have a way of entering even the smallest cracks in concrete and corroding the rebar inside, which causes concrete to spall. This difficulty is most acute in Brutalist structures, where a botched patch job might ruin the integrity of a building such as Louis Kahn’s 1965 Salk Institute for Biological Studies in La Jolla, California.

“Concrete conservation is a fledgling area of practice, which is why we’ve turned our attention to it,” Macdonald says. “There are two scales of urgency: Get information out into the field, but at the same time, do the research work.” The GCI actively develops and distributes guidelines about how to best select materials and conduct repairs that are sympathetic to the architecture. The CMAI, meanwhile, is ramping up scientific work around concrete construction over the coming year.

Macdonald notes synergies between the GCI’s extensive research on conserving Modern art and conserving Modern architecture. Both initiatives engage questions of how industrial advances permeated the greater culture, such as the migration of wartime materials—plastics and other synthetics—into painting and sculpture. “The detailed research into art materials flows through to building materials, but an art object isn’t subject to use,” she says. “At Salk, for instance, the use of the place is crucial to its importance. It must be sustained as a building. We can’t have empty buildings hanging around—it’s not an art gallery.”

The renovation of the Salk Institute was initiated by the CMAI as a way of supporting its overall aims. After decades of exposure to sun and salty marine air, the institute’s concrete and signature teak windows were restored. Notably, the conservation of the complex is both applied and strategic. The seemingly boring management documents that lay out how a piece of architecture should be maintained are critical to its life span. Macdonald stresses the conceptual connective tissue between Kahn’s design and Jonas Salk’s desire for a place for scientific collaboration. “You have to understand the place and understand why,” she says. “Writing that down in the conceptual planning document will be instrumental for future generations.”

Enter Keeping It Modern. The program, now in its sixth year of granting, was started by the Getty Foundation to help stewards of 20th-century architecture move from ad hoc conservation and stopgap repairs to longer-term planning. Individual grants ranging from $100,000 to $200,000 are disbursed through open competitions judged by an international group of advisers. To date, the Getty has supported the conservation of 54 buildings in 29 countries.

Antoine Wilmering, senior program officer for the Getty Foundation, explains that one factor in the selection process is how applicable the issues tied to one project are to other architectures of the Modern era. “Could this influence how other buildings are preserved?” he asks.

For example, the impact of the conservation of the Gandhi Bhawan by Pierre Jeanneret—Le Corbusier’s cousin and a collaborator on his vision for Chandigarh, India—goes beyond the single 1961 brick-and-concrete building and even beyond the Panjab University campus where it sits. In the development of their conservation management plan, the grantees organized a workshop on Modernism in South Asia that brought together stewards, experts, and professionals from across India to share research and strategies.

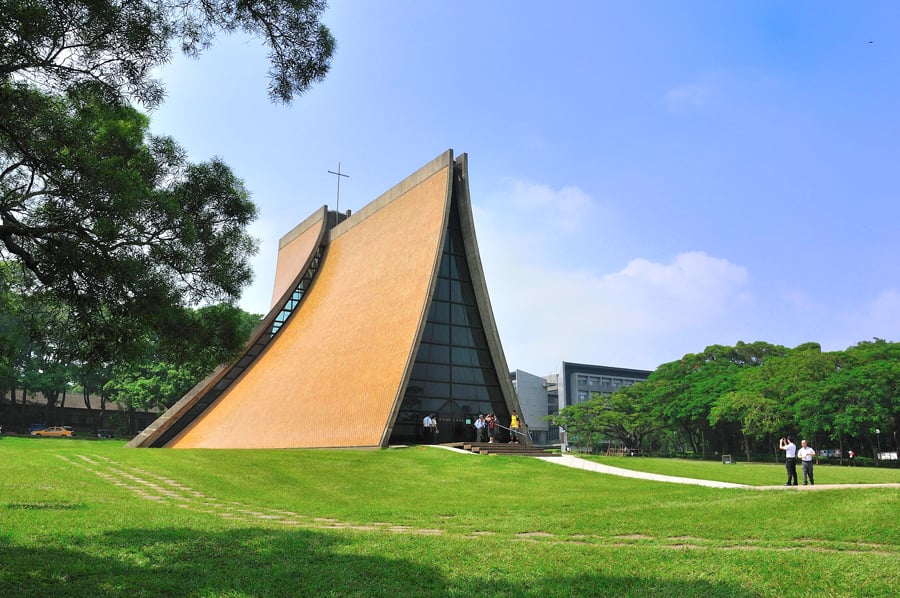

Standout grantee projects exist on six continents, with more and more located outside the canonical loci of Western Europe and the United States: sub- Saharan Africa, India, South America, Eastern Europe. “One of the biggest challenges is that buildings [in these regions] are not recognized for their value. Developers think they can put in a bigger or better building,” notes Wilmering as he discusses the 1963 Henry Luce Memorial Chapel at Taiwan’s Tunghai University. An early work by I.M. Pei and C.K. Chen, the A-frame, diagrid building required a conservation plan. But the project, which pays homage to traditional Chinese temples, was not well known. The Keeping It Modern grant to the university helped raise awareness of the importance of Modern architecture in Taiwan, and of the building in particular, which recently received a national historic listing.

On the other end of the Keeping It Modern spectrum, icons such as Jørn Utzon’s Sydney Opera House offer a different lesson: Already-protected buildings need not rest on their laurels but can use their heightened visibility to further the conservation cause. Ian Cashen, executive director of building safety and security at the opera house, explains that the grant fostered the development of new techniques for conducting “tap test” inspections of the concrete and tile that make up the sail-like roof. University of Sydney researchers created a tool that combines a tapping hammer with a microphone and thermal and force sensors. The data collected can be synced with BIM and Revit software that monitors the whole building, tracking areas in need of repair. Cashen and the opera house team are also investigating the use of drones to take high-resolution and thermographic photographs to gauge deterioration or changes. “Long-term, we want to use this information to develop machine learning algorithms to pinpoint deterioration in each of the 3,382 tiles that cover the opera house sails, and any deterioration to the shell structure,” he says.

The use of drones and algorithms to conserve a building nearly half a century old gives us a conservationist spin on Mies’s quote: All architecture is bound up with its own time, but to thrive and continue into the future, it must open itself up to the media, methods, and technologies of each evolving epoch.

You may also enjoy “The Statue of Liberty Museum Opens in New York City.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025