January 22, 2021

Has the Pandemic Changed the Experience of Encountering Art in Public?

With limited access to indoor galleries and museums, New York’s public art commissions seem more important now than ever.

Public art is an innate cultural privilege for New Yorkers. Top-notch art can be found across the city’s boroughs everywhere from parks, squares, alleys, and rooftops—sometimes to the jaded disdain of passerby. While permanent staples, such as Robert Indiana’s Love on 6th Avenue or George Segal’s Gay Liberation at the Stonewall National Monument are ingrained in the urban texture, others are more ephemeral. Public art has the power to swiftly take over Instagram feeds but also has a history of sparking polarizing interpretations at town hall hearings.

Following COVID-19 restrictions, art—not unlike other sectors such as restaurant and show business—has faced an unparalleled need to move outdoors. When asked about public art’s changing role amidst the pandemic, Sandra Bloodworth, director at MTA Arts & Design, rhetorically responds: “How long do you have?” She says, “Since starting a public art program within the transit system in 1985, we’ve always been working out of a challenged environment which art serves to enhance.”

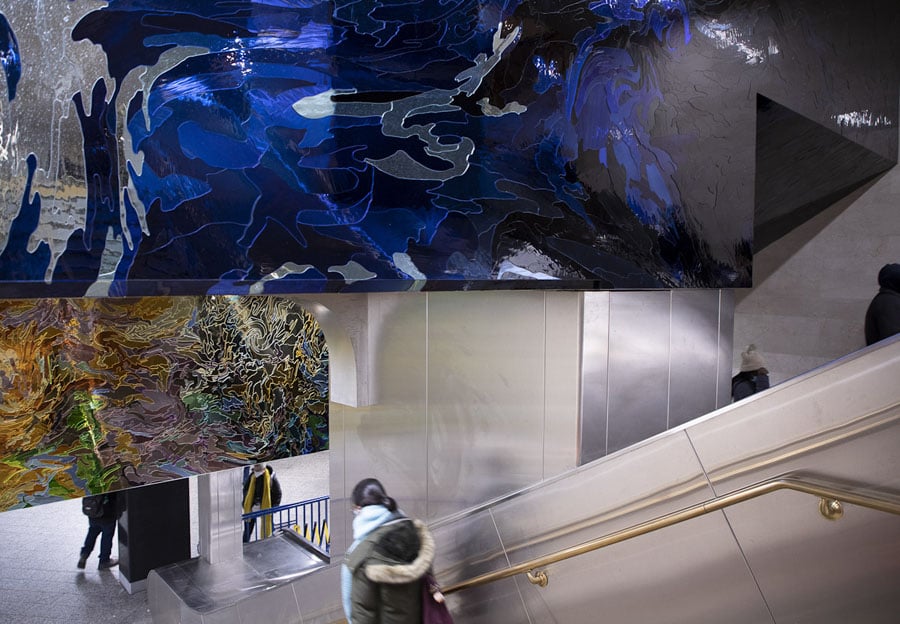

The organization’s most recent project is an installation in Grand Central Station by established artist Jim Hodges titled I dreamed a world and called it Love. The 710-square-foot mirrored glass mosaic is composed of 5,000 tiles in 70 different hues. Bloodworth sees it as “a statement of hope,” that plunges passengers into a sea of oscillating waves as they descend to the platform. With 350 works on view across the subway system (as well as Metro North and the Long Island Railroad) the initiative considers its program New York’s underground museum.

Whether 100 years or less than a month old, train stations and other transit hubs make ideal backdrops for permanent commissions that often graduate into local symbols. A more recent vision for the city’s transportation system is Public Art Fund’s latest installation at the new SOM-designed Moynihan Train Hall. With a soaring iron and glass dome prompting passengers to look up, the ceilings of the former post office seem to be prime real estate.

Designed by Scandinavian artists Elmgreen & Dragset, The Hive is a sculptural orchestration of miniature LED stainless-steel skyscrapers suspended from the ceiling. The installation represents an über-metropolis—a medley of fictional buildings alongside realized high-rises from global megacities. According to the duo, the piece hovers as a “a world turned on its head.” Skyscrapers such as the Empire State Building change colors in this rendition, which the artists conceptualized before the pandemic and realized within an eighteen-month fabrication period.

In contrast to the site-specificity of these two projects, conceptual artist Jill Magid takes a different approach to “public art.” In her Creative Time project, Tender, she highlights the transitory nature of commerce by circulating 120,000 2020-dated pennies, the exact worth of the United States’s first stimulus check. Magid’s pennies, however, are unconventionally inscribed with the phrase “the body was already so fragile.” The piece’s power relies on silent activations through monetary transactions, passing through the hands of a public unaware of its participation. The artist has been traveling to bodegas across New York to disperse the pennies—the art—as these businesses have remained open throughout the pandemic.

The antimicrobial nature of copper renders the penny a safe way to touch art, which according to the organization’s executive director Justine Ludwig, “can add a sense of wonder or the sublime to the quotidian rhythms of one’s life.” The project pushes the borders of traditional public artworks with its transient nature that pierces the mundane.

Acknowledging the significance of this moment Nicholas Baume, the director and chief curator at Public Art Fund says, “A key reason that public art is so important now is our renewed sense of community: It reminds us that we must all take responsibility, that we must all have equal access, and that we must all treasure and support our public domain as a site of creative expression to reflect our democratic values and lift our collective spirits.”

You may also enjoy “Six Virtual Experiences Worth Getting Lost In”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis Webinars

Connect with experts and design leaders on the most important conversations of the day.