February 16, 2023

The Architect of Art Nouveau Who Brought Beauty to the Masses

The Architect Who Gave Paris Its Curves

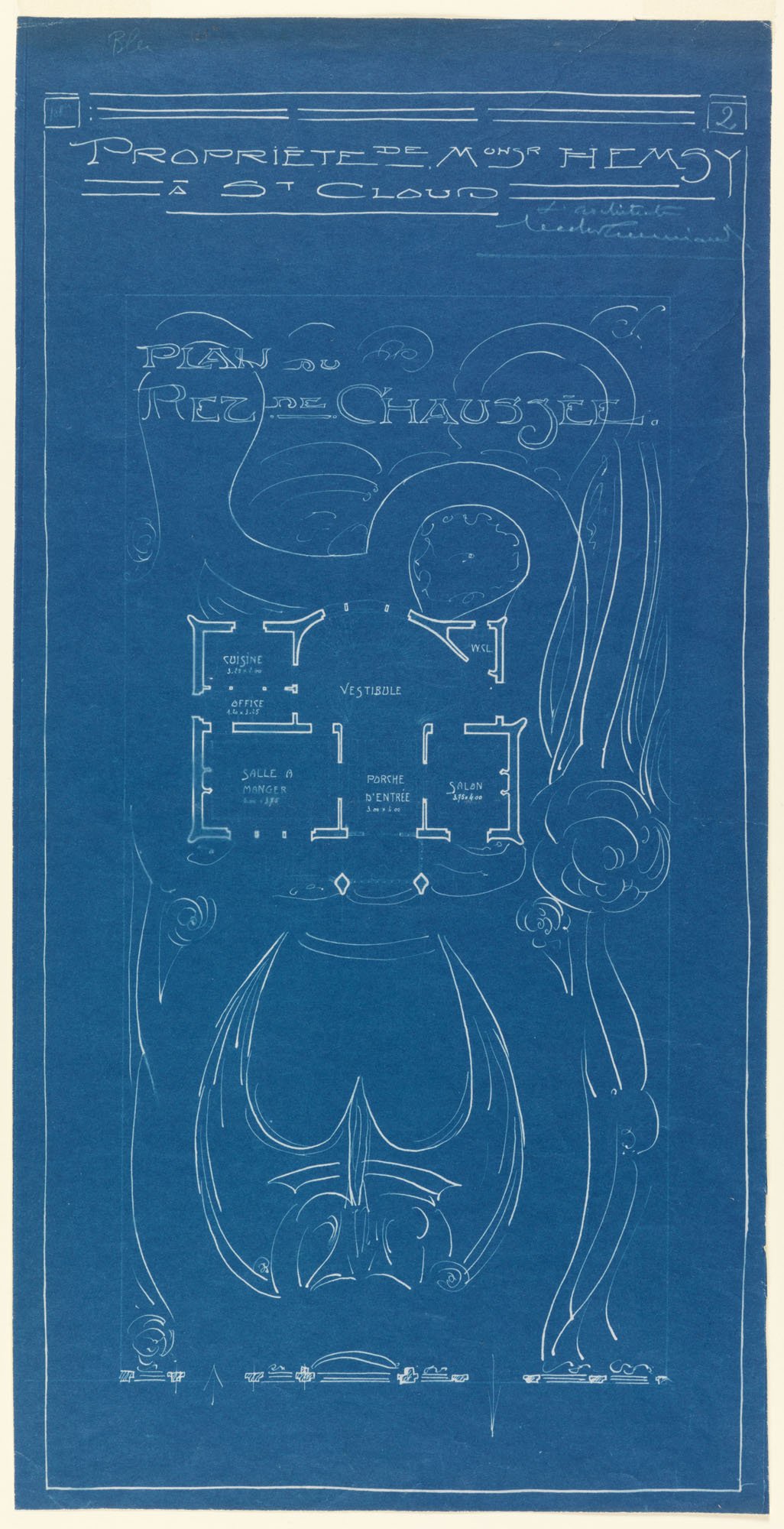

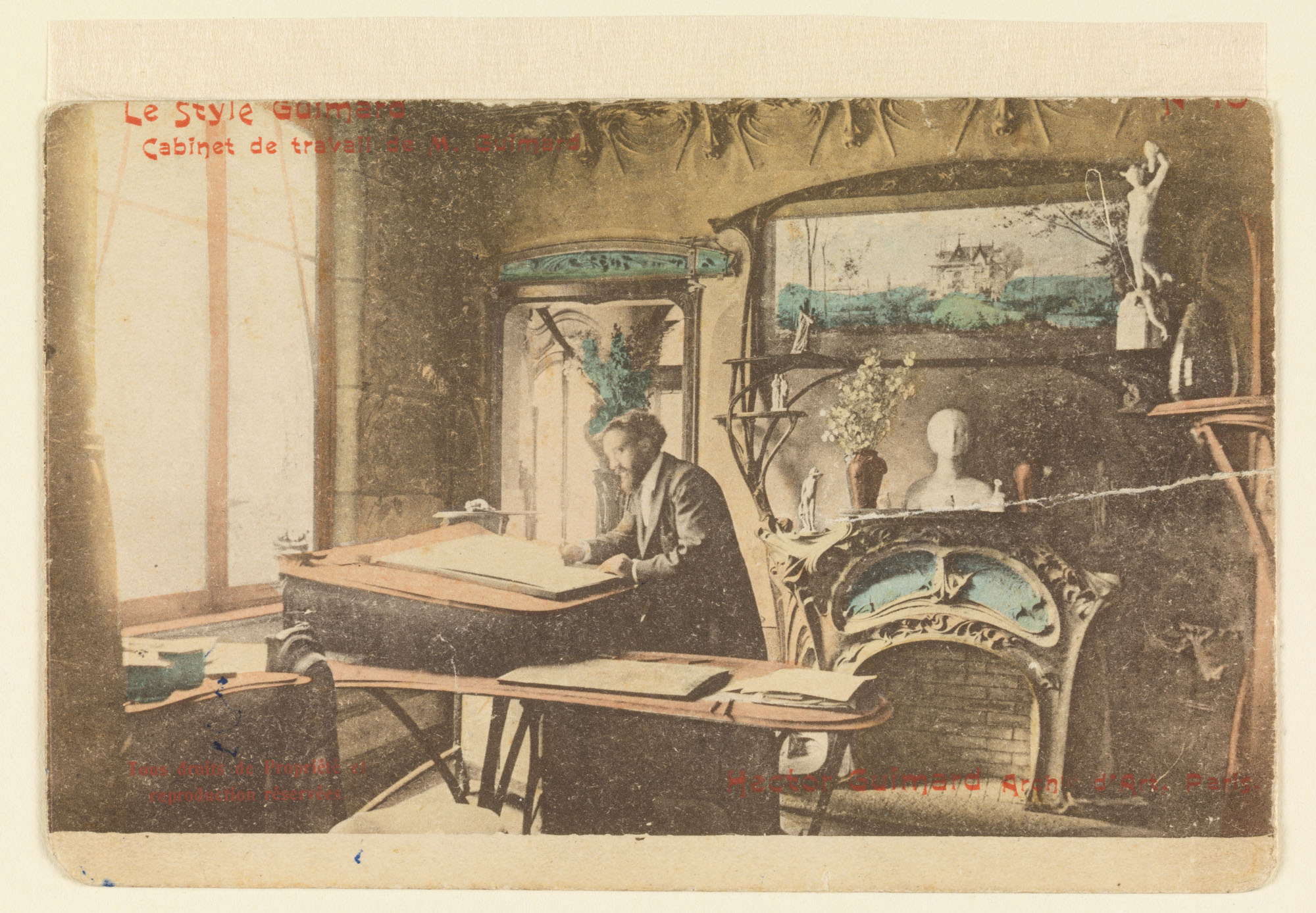

For Hector Guimard (1867–1942), the goal was always to “put the beautiful within reach of everyone.” From Paris’s sinuous Métro station entrances to the intricate design of his wife’s wedding dress, Guimard dedicated every aspect of his life to creating unity between the architectural, decorative, and fine arts. Yet while Guimard quickly became France’s most famous Art Nouveau architect, breaking from the classical and revivalist styles of the 19th century, he died in relative obscurity in the United States, leaving much of his extensive oeuvre overlooked in the canon of architecture and design history.

A new exhibition sets out to change that. By considering Guimard’s processes and marketing strategies, Hector Guimard: How Paris Got Its Curves provides a fascinating look at the life and work of this influential designer, showcasing nearly 100 objects including furniture and cast-iron architectural elements alongside jewelry, textiles, wallpaper, typography, drawings, and photographs, as well as other products, plans, and marketing materials. Co-organized by the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum and Chicago’s Richard H. Driehaus Museum and on view through May 2023, the ornate naturalistic designs on view tell the story of Guimard’s eponymous “brand,” Le Style Guimard, and its radical vision for industrial design.

Beyond the Paris Métro

While visitors will be entranced by the Gesamtkunstwerk of Guimard’s life, including his designs for his personal residence and studio, Hotel Guimard, the highlight of the exhibition is the architect’s lesser-known collection of designs for several housing projects from the 1920s. In the context of the post–World War I housing shortage, Guimard’s foray into housing reflected his socialist leanings and advocacy of human rights. Works on view such as drawings for a Design for a Mass-operational House (1920) and Standardized Rural House (1920) display an early recognition of modular building systems including roofing tiles and interlocking concrete blocks. Guimard wasn’t developing prefab methods only to radically rethink the construction process.

Art historian Barry Bergdoll writes in the accompanying catalog that he “was thinking through the implications of … sequencing to the nature of labor on the building site.” By embracing new building materials such as masonry, glass, cast iron, and concrete, Guimard’s work not only signaled a transformation of the city but also displayed a sustained effort to make the Art Nouveau style accessible and affordable to the masses.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Related

Products

How the Furniture Industry is Stepping Up on Circularity

Responding to new studies on the environmental impact of furniture, manufacturers, dealers, and start-ups are accelerating their carbon and circularity initiatives.

Viewpoints

The 2024 Net Zero Conference Highlights the Importance of Collective Action

Last month, leading climate experts convened at the Anaheim Convention Center to reenvision the built environment for a net zero future.

Projects

McDonald’s Reimagines its Interiors through Radical Circular Design

A pilot program launching in McDonald’s France and Belgium aims to create sustainable interior renovations for the global fast-food brand