October 9, 2017

“Heliomorphic Chicago” Tinkers With the City’s Iconic Buildings to Create a More Equitable Skyline

On view at the Chicago Architecture Biennial, the installation advocates for a return to a “collective urban form.”

Courtesy Charles Waldheim

At this year’s Chicago Architecture Biennial, the so-called Tower Room was clearly conceived as the culmination of curators Sharon and Johnston and Mark Lee’s exhibition, Make New History. Rows of 16-foot-tall towerlets—doubly belated “entries” to the 1922 Chicago Tribune Tower competition—were installed in the Chicago Cultural Center’s elegant Yates Hall. Visitors preoccupied with Instagramming Tatiana Bilbao’s plug-in-play tower (made up of compositional non-sequiturs) or those scratching their heads at OFFICE KGDVS’s obvious send-up (a bizarre design featuring massive murals of geckos) may have missed another miniature city of wonky towers, Heliomorphic Chicago. Emblazoned red and loosely arrayed into a gridiron, this more modestly scaled installation comprises diminutive high-rises both angular and smooth, a bit reminiscent of the warped geometric designs of Morphosis. A closer look reveals that the towers are grouped in sets of doubles; like siblings, each of the couples seems drawn from the same genetic pool as its correlate, yet is phenotypically distinct.

These isomorphic pairs express different facets of a central theme, that of “heliomorphism.” This abstruse term has recently been taken up by architect Charles Waldheim and his Office for Urbanization, a research group based out of the Harvard University Graduate School of Design. The Office was formally launched in September 2016 with a two-day seminar featuring keynotes from Jeanne Gang and Thom Mayne. Central to but absent from the proceedings was Ralph Knowles, a pioneer of solar envelope zoning. The outfit’s first project, unveiled at the conference, reinterpreted New York City’s 1916 Zoning Resolution through the filter of Knowles’s rich studies, largely undertaken throughout the 1970s and ’80s. The results were frenetic: Hugh Ferriss’s sheared skyscrapers, originally conceived as a visual means to publicize the city ordinance, were parametrically extended and distorted to create a totalizing skyline of shards and pyramids.

What separated this from the solar analysis provided by BIM plug-ins was the Office’s dual focus on energy optimization and urban equity, or public access to sunlight and views. These values are reconciled with floor area ratios, which tethers the group’s work to the realities of the profession. The initial New York exercise, Waldheim explains, “allowed us to find a way to connect the formal and cultural ambitions of architectural practice to an anthropological question.”

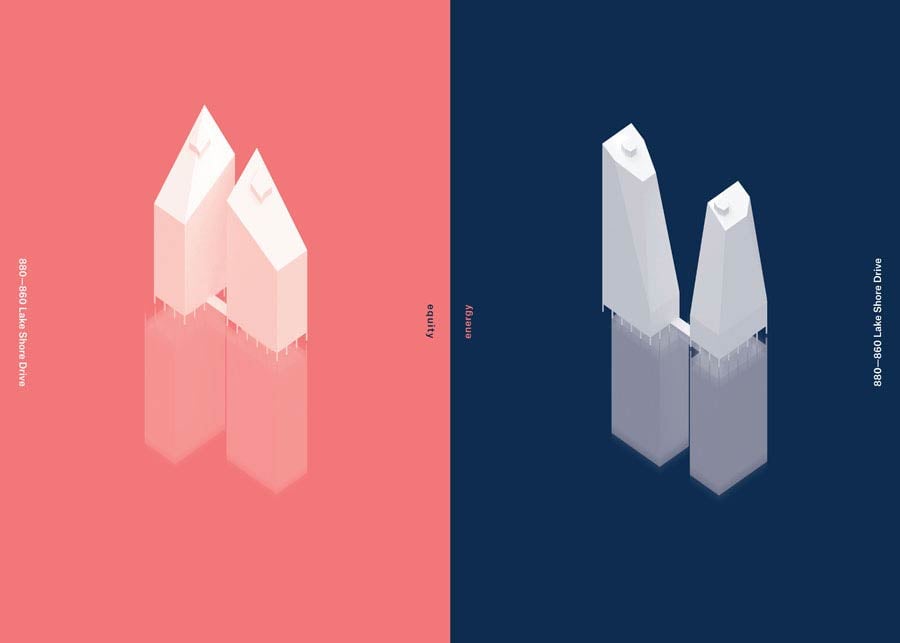

Heliomorphic Chicago applies a similar methodology to that city’s famous office buildings, particularly those in and around the Loop. With this wealth of source material, Waldheim chose to play off the iconographic character of landmark buildings such as Mies van der Rohe’s Lake Shore Drive apartments and Bertrand Goldberg’s Marina City. “We were interested in identifying towers that would somehow be legible in their own right,” he says. “The Trump Tower is in there for good measure.”

Courtesy Harvard GSD Office for Urbanization with Siena Scarff Design

By manipulating these iconic buildings, Waldheim and his team also unload them of their ideological baggage. As quintessential Modernist gestures, the brazen rectangular prisms of Lake Shore Drive were and remain a shock, yet they are remarkably inefficient in context, as the Office’s malformations demonstrate. In Heliomorphic Chicago, the complex is rendered unrecognizable, “its proportions totally obliterated,” Waldheim admits. “Seeing it made me almost wistful for the original.” Elsewhere, the Willis Tower’s dramatic setbacks are smoothed into a more integrated, icicle-like whole. Jeanne Gang’s Aqua Tower, similarly streamlined, is bereft of its trademark scalloped terraces. Not even Marina City’s corn cobs are sacred; the twin stalks are stretched upwards to make insipid copies of the Goldberg originals. (Despite the Office’s disclaimer to preserve certain characteristics of the works, many of the models strain the legibility the procedure aims to preserve.)

Meanwhile, Helmut Jahn’s endangered James R. Thompson Center survives more or less intact. As does the Hancock Tower, though it looks as if it’s been given a 2017 update (adopting the pleats of SOM’s One World Trade Center). Like many of the buildings the Office tinkered with, it has been rotated on its site.

But that’s just one part of the picture. Drill into the Office’s core criteria and sharper divisions come to the fore. From an energy point of view, Lake Point Tower, a 70-story high-rise that stands at the edge of Lake Michigan, undergoes relatively minor alterations to its massing. (Mies acolytes John Heinrich and George Schipporeit designed the curvilinear tower-on-a-plinth to withstand winds coming off the lake.) Adjusted for “equity,” however, and the graceful building becomes a homely stub, repositioned to the west of the plot, off-axis, thereby freeing up views to the Navy Pier and the water beyond. In fact, the effect plays out nearly the same across the board: both residential and offices towers are shown to be woeful neighbors and have an adverse effect on the city blocks around them.

Courtesy Harvard GSD Office for Urbanization with Siena Scarff Design

While Waldheim insists that such work is intended to generate architectural discourse, he also suggests it could potentially have real-world applications. Because the Office’s research has a morphological bent, it can be readily used as a visual communication tool, particularly for cities that are considering swaths of new infill developments. The environmental effects of these building projects are assessed in an incredibly localized way, stretching the extent of a city block but rarely further than that. Yet their impact can be immense, as covetous high-rises tend to cast deep shadows.

Of course, there already exist tools that gauge the effects of prospective developments, specifically energy use and solar gain. But what these cities don’t have at their disposal, Waldheim says, “is the capacity to study formal alternatives.” Developers (and, playing a supporting role, architects) steer the conversation; they may be asked by a planning department to tweak or further justify a proposal, but in key ways they have the upper hand.

“What we can give cities is the ability to make a counter-proposal,” Waldheim offers. “We seem to have lost the capacity for doing that. We can talk about urban policy or individual architectural objects or one-off projects. But what we need to return to is the collective urban form.”

You may also enjoy “For This Solar Design Pioneer, Architecture Is Synonymous With Energy.”