May 6, 2022

The Second Edition of Homo Faber Was a Celebration of Craft and Heritage

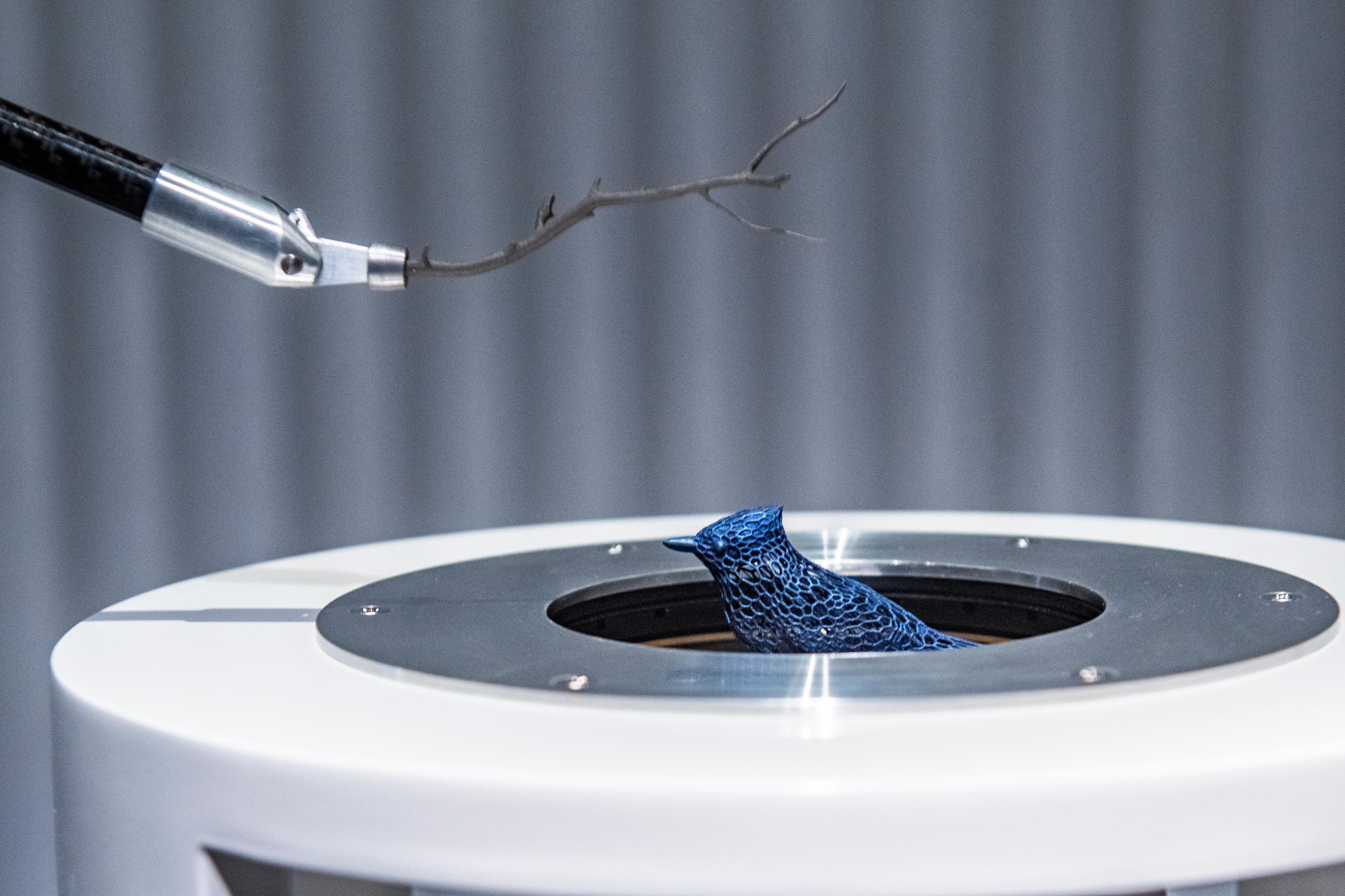

In his 1968 book The Nature and Art of Workmanship, David Pye, a professor of furniture at London’s Royal College of Art in the mid-century, described craft as ‘the workmanship of risk’—unlike processes that lead to predetermined outcomes, it depends on the judgment, dexterity, and care of the maker. Homo Faber is a grand celebration of this idea—with works ranging from Finnish origami artist Juho Könkkölä’s intricate human figures made from a single piece of paper to ceramics and kimonos and lacquer work by 12 of Japan’s National Living Treasures. Part of an exhibition curated by designer Naoko Fukasawa, the works on view in the latter rely on knowledge embedded in the hands and heads of people and passed down through generations.

One space shows collaborations between historic porcelain manufacturers and contemporary artists and designers, including Paris-based Argentinian artist Ruth Gurvich’s delicate forms and grand cabinets by Brazil’s Campana brothers. Students from Swiss design school École cantonale d’art de Lausanne (ECAL) have created a playful series of interactive works in collaboration with artisans who make “mechanical art”, while curator Tapiwa Matsinde has filled a lounge space with domestic objects, particularly focusing on makers from Africa from work by Lagos based furniture brand Ilé Ilà, founded by Tosin Oshinowo, to baskets by the Ilala weaver community from the KwaZulu-Natal region of South Africa.

Since the event’s last edition in 2018 there has been an uptick of interest in craft, as people searching for tactility and sensory stimulation in the face of successive lockdowns have turned to sewing, pottery, gardening and baking in their hoards. Hand skills have also entered the cultural discourse in other ways—as a foil to our increasingly digital lives, as a counter to automation and as part of a slower, more conscious and sustainable pace of manufacturing. The subheading for Homo Faber—crafting a more human future”—strives to position the work here as not just as a show of luxury items for the homes of the rich or parallel art world, but as part of a necessary ethical turn.

Social commentary is embedded in several works: a special commission by design studio Zanellato/Bortotto of mosaics inspired by the floors of the city’s Basilica di San Marco allude to the erosion caused by the city’s exposure to the sea, while many of the artists chosen for an exhibition titled Next of Europe create work tackling urgent subjects such as migration, racism and climate change.

Homo Faber leaves one with no doubt of the appeal of handcrafted objects and the extraordinary talent, patience, skill and ingenuity of those who make them. Nonetheless, amid the beauty on display, one feels as if the event has not quite answered its own call to action by demonstrating the importance and transformative power of the making, rather than the aesthetic and artistic value of objects––nor the diversity and global span of radical making traditions. One hopes that future events will embody the kinds of risks Pye described as central to craft, revealing more of the mess, humanity, politics and social context behind these works––how human skills have shaped our world and continue to do so.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

- No tags selected

Related

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Products

Behind the Fine Art and Science of Glazing

Architects today are thinking beyond the curtain wall, using glass to deliver high energy performance and better comfort in a variety of buildings.