February 5, 2025

How Can Designers Listen to Water?

“Rivers have a memory,” said Colombian environmentalist Josefina Klinger Zúñiga, during a day of dialogue at re:arc institute’s Architecture of Planetary Well-being symposium hosted in Bogotá, Colombia, in early 2024. She continued: “If you want to learn about values, read the water. And if you want to learn about justice, go to the river.” Throughout the panel discussion aptly titled “From Poetry to Practice,” the ancient idea of listening to water submerged the audience—metaphorically and literally.

That day, I was invited to various moments of deep listening—through traditional dance and music, poetry, and thoughtful design presentations that highlighted the intersections of our social and ecological systems. Midway through the day, Catalina Mejia Moreno, senior lecturer in climate studies and spatial practices at Central Saint Martins, took the stage with her collaborators Felipe Arturo and Gabriela Leandro Pereira to lead the audience through an experiential interlude titled Pororoca: Abraz(ç)o de río e mar, or “I embrace the river and the sea.”

Their research began in Salvador de Bahia, where Moreno, Arturo, and Pereira learned about the resistance struggles of Brazil’s Baiana communities that are sustained in relation to their waters. Arturo continued, “We visited lagoons, ancestral fountains, and quilombos, sandbanks, dunes, seawalls, and coastal neighborhoods destroyed by modernization and urbanization processes but rebuilt by collective networks.”

Over the course of about 30 minutes, the researchers spoke practically and poetically while viscous projections of the Paraguay River covered the walls of the room. At one point, the trio took out a massive roll of black-and-white fabric, digitally printed with the texture of the ocean. Passing it over our heads, across rows and rows of seats, it eventually reached the back wall. The image of the sea washed over us, symbolically immersing us in its powerful waters. Arturo instructed us: “At some point scissors will appear. We hope you will cut some fragments and pieces of this fabric—scarves, ponchos, handkerchiefs to wipe your tears, curtains, as you wish—but we invite you above all to listen.”

A Place Without Borders

The Pororoca interlude perhaps left us with more questions than answers. Where does the river end? Where does the ocean begin? “What is the space that these waters share—is it a region? An edge? Two molecular bodies in collision?” Arturo asked.

When we design with water, we forgo clear borders, as we do the other constraints of land. In its 2019 report “Ocean Energy Landscapes: Energy Infrastructures Towards Greater Local Sovereignty in Patagonia, Argentina,” re:arc institute Practice Lab grantee Región Austral writes: “It is imperative to think of the sea as an opportunity, a site from which the nation can reimagine a future sustainable relationship with its coasts and territory, leaving behind the current continental and introspective view.” During its symposium presentation, Región Austral showed the audience how its work integrates research, practice, policy, and implementation.

Re:arc’s funding will help Región Austral to design and build public spaces and community infrastructure for Buenos Aires’s Playón de Chacarita community. As one of over 2,000 informal settlements within the metropolitan region of Buenos Aires, Chacarita “typifies the challenges faced by informal settlements in Latin America.” When the city government started an integration process for the neighborhood in 2017, it left a lot in terms of vacant space and little in terms of green infrastructure.

To fill this gap, Región Austral conducted participatory workshops, interviews, and discussions around four topics—culture, environment, economy, and health—with more than 70 residents. Alongside various governmental agencies as well as local NGOs and cooperatives, community members were able to actively shape the design and construction of the project that includes an open agora, a sports court, a community center, and the Guevara Garden, which serves as both a pocket park and a rain garden. “The idea is to introduce vegetation that consumes very little water as well as fruit trees to mitigate flooding during the rainy season,” Región Austral cofounder Soledad Patiño explained. “We believe that although small, these interventions will contribute to reduce the urban heat focus and improve environmental comfort.”

Designing with Megadiversity

“Vulnerability” was a critical idea discussed throughout most of the day’s presentations. When it was time for the Office of Urban Resilience (ORU) to present, they began with a sobering quote from the World Meteorological Organization: “Latin America and the Caribbean is one of the world regions where climate change effects and impacts such as heat waves, decreases in crop yield, wildfires, coral reef depletion, and extreme sea level events are projected to be more intense.”

The following slides detailed how ORU approaches design within Latin America and what they call “a megadiverse environment.” While the 33 countries of Latin America and the Caribbean may share borders and waterways, they each face their own unique challenges—socially, politically, and environmentally. Mexico, for example, faces significant water scarcity, especially in its northern regions, where the landscape is further affected by global warming and the over-extraction of groundwater. Aging and inefficient water infrastructure exacerbates the water loss, with estimates suggesting that up to 40 percent of treated water is lost through leaks.

ORU aims to address some of these concerns with its re:arc-funded San Felipe Water Intelligence Hub, located on the outskirts of Oaxaca in San Felipe del Agua. The space is intended to be a hub for innovation, conservation, and heritage and will help play a vital role in preserving the ecosystem and habitat of the upper Río San Felipe basin through monitoring and education programs. “Our vision involves an ecotourism model that offers hiking and bird-watching activities, thus establishing a new destination and creating economic development opportunities for the community,” the studio explained.

At the heart of ORU’s work is a desire to change the current management of water “from a linear model of water extraction to a decentralized and circular model, treating urban water as a resource and not as a waste.”

Fostering Collaboration

José Pablo Ambrosi and Loreta Castro-Reguera of Mexico City–based Taller Capital are grappling with similar water management concerns.

Founded in 2010, Taller Capital focuses on urban interventions that prioritize densification and infrastructural public spaces. “We design infrastructural public spaces to fix the broken city,” Castro-Reguera explained in a video presentation on their Practice Lab project titled Pooling Xolox, which transforms the historic pre-Hispanic town of San Lucas Xolox.

The former village was once located near the former lake of Texcoco, in the Basin of Mexico. “Through re:arc’s practice-based funding initiative, we reconnected with the local community. Specifically, the group of Ejidatarios, which own the land and have jurisprudence over it,” Castro-Reguera noted. “Previously, water runoff from the mountain went into the lake, but the construction of the new airport desiccated the lake, causing floods.”

Taller Capital invited the local potable water system that manages drinking water, irrigation, and sanitation to collaborate on the project. Together, they worked to mitigate the flooding and address runoff management concerns caused by the new airport, reusing the water for agricultural irrigation while introducing a communal area for recreational and cultural purposes. Rather than piping rainwater that runs from the mountain, they contain and redistribute the runoff. Because water piping is “an expensive and unsustainable measurement,” they created soft infrastructure and community space that serves as an “ecosocial catalyst” and “recovers water culture” in the town. Taller Capital believes Xolox can set an example on how to integrate public life and water management in the Valley of Mexico.

Embracing Fluidity

I left Bogotá feeling hopeful in the face of oftentimes-hopeless climate discourse and grateful that emerging nonprofits such as re:arc are dedicating themselves to supporting the designers and grassroots initiatives working at the intersection of architecture and climate. My experience proved to me that by designing with, not against, water systems, architects and urban planners can create equitable, sustainable public spaces that promote both personal and planetary well-being.

As Zúñiga asked at the beginning of the day’s events, “What happens when people begin to speak the languages of the mangroves, the waves, the tides?” We may be learning the language, but let’s not forget to listen.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

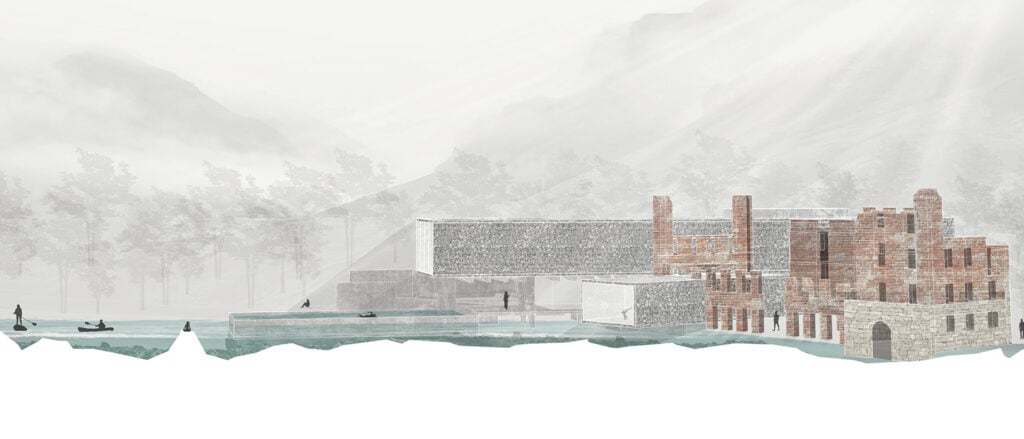

These Architecture Students Explore the Healing Power of Water

Design projects centered on water promote wellness, celebrate infrastructure, and reconnect communities with their environment.

Projects

KPF Reimagines the Arch in a Quietly Bold New York Facade

The repetition of deceptively simple window bays on a Greenwich Village building conceals the deep attention to innovation, craft, and context.