March 9, 2018

In the Aftermath of Violence, Forensic Architecture Reconstructs the Truth

An expansive show at the ICA in London demonstrates how the activist research group uses spatial reconstructions to uncover human rights violations.

On January 1, 2016, while the rest of the world was ringing in the new year, team members of Forensic Architecture were busy assembling a crude pavilion in the Negev-Naqab desert in southern Israel. Built in collaboration with Bedouin and anticolonial organizations to be used as a civil forum, the pavilion comprised a simple wooden frame lined with black tarpaulin. This enigmatic pavilion is the only built structure on display at Counter Investigations, Forensic Architecture’s (FA) new exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London.

For those familiar with the work of the multidisciplinary research agency led by architect Eyal Weizman of Goldsmiths, University of London, this will come as no surprise. Far from artisans of built form or typological exploration, FA deals with reconstruction, discursive space, and memory, often through journalistic and investigative methodology. As nebulous as this may sound, FA is probably having more of an impact than any self-defining architect working in the field today.

The desert pavilion, built for a project called Ground Truth, is a useful example not just as a point of exception, but also to demonstrate what FA is constructing in its work. The pavilion served as a claiming of space to consolidate historical and juridical evidence on behalf of unsanctioned Palestinian villages in the Negev-Naqab desert. The pavilion is thus a backdrop, to a broader process of constructing truth and concrete memory in a landscape of displacement and falsification.

This is a thread that runs through much of Counter Investigations. As its title suggests, the show is as devoted to processes as it is to outcomes. Projects taken on by FA are presented like cases meticulously laid out in a court of law. Communicated predominantly with films accompanied by cartographic and chronologic displays, they often center around highly distressing moments of violence: Halit Yozgat, an immigrant living in Kassel, Germany is killed by a neo-Nazi in 2006; two Palestinian teenagers are murdered in the street by Israeli security forces in 2014; a US drone strike hits a house in Waziristan, Pakistan in 2012.

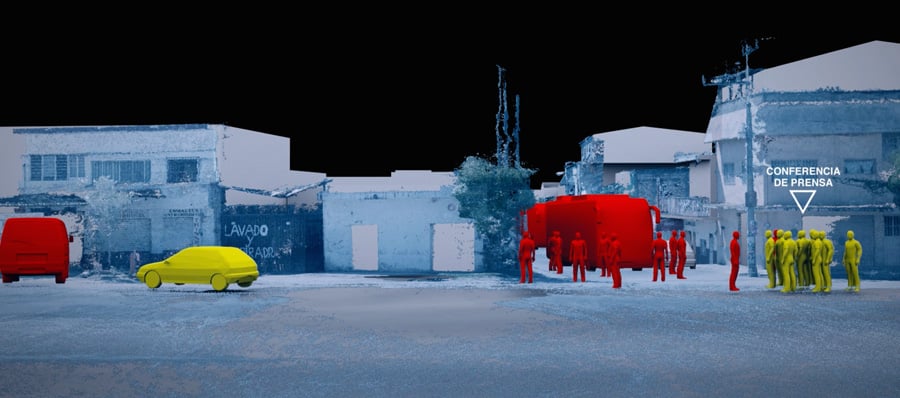

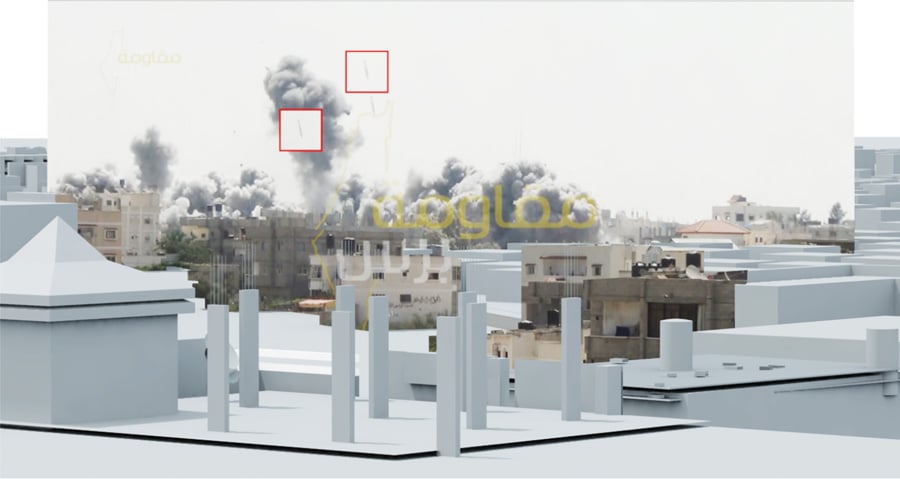

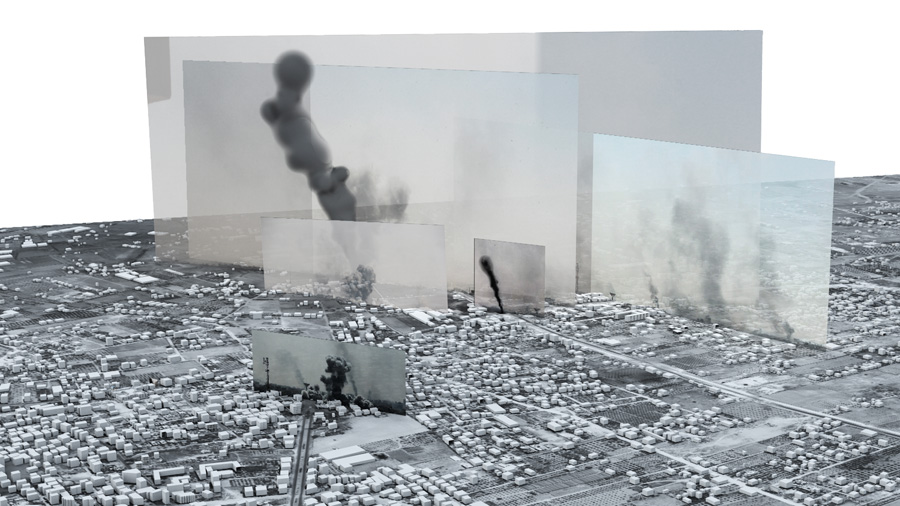

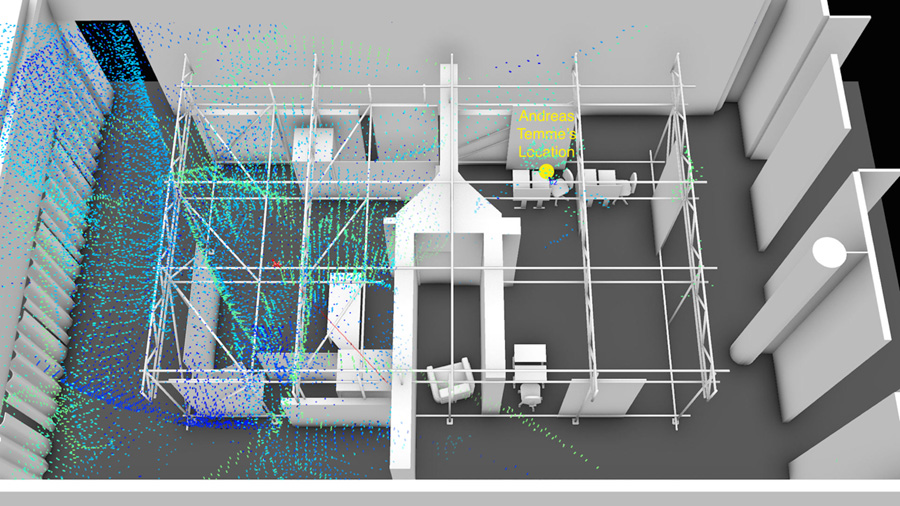

By painstakingly piecing together media fragments such as cell phone videos, news footage, and publicly accessible data such as wind direction or sun position, FA recreate events which are otherwise hidden from view. These reconstructions bear witness and form evidence of human rights abuses as “counter forensics,” in an attempt to, according to the group, “invert the institutionalized forensic gaze.”

For example, in the case of the drone strike in Waziristan, smuggled phone footage captured in the immediate aftermath is used by FA to construct a panoramic image which can verify the attack’s location and facilitate the digital reconstruction of the building. Using further footage taken from inside the building after the explosion, traces of steel fragments help to identify the precise point at which the missile exploded and what type of missile was used.

The attention to the minutiae of these events—to each fragment of time and matter implicated in these moments of violence—is, quite simply, astonishing.

Yet there are more than just technological acrobatics for the gallery viewer. Bringing FA’s work into the gallery space provides an opportunity for Weizman and his team to further share the concepts underpinning their work.

As part of the extensive show, the group’s first U.K. exhibition, Weizman has organized a series of seminars to teach some of the broader concepts to a broader audience. “We’re going to teach techniques and do citizen investigations. Usually our evidence is presented publicly or politically or juridically, in these kinds of forums, but now we just want to open a forum to investigate them culturally,” he explains. “We want to emphasize all the ground floor issues of migration and attitudes towards migrants in Europe. We think this is very topical now in the U.K. as it works out what it is.”

Crucially, FA’s work is employed across more fields beyond cultural and educational spaces, with concrete legal and political implications. This is demonstrated with a large graphic accompanying the case of Halit Yozgat, which shows how FA’s work moves between media, cultural, political and legal fora. Most importantly, it demonstrates how FA’s work is used to produce and present evidence in pursuit of public accountability.

In the Halit Yozgat case, evidence produced by FA via the reconstruction of the internet cafe where the Turkish immigrant was killed is part of an ongoing investigation into the unexplained presence of a German intelligence officer at the scene of the crime.

Similarly, a report on the Saydnaya Prison in Syria, produced in collaboration with survivors and Amnesty International using sonic and spatial reconstructions was denounced by Bashar al-Assad himself, who called it a fabrication meant to “vilify and smear the Syrian government.” There is perhaps no higher indication of the timely vitality of FA’s work than this.

Counter Investigations is on view at the ICA in London through May 6, 2018.

You might also like “Renowned Indian Architect B.V. Doshi is 2018 Pritzker Prize Winner.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025