April 16, 2018

Here’s How You Design for Living and Working in Outer Space

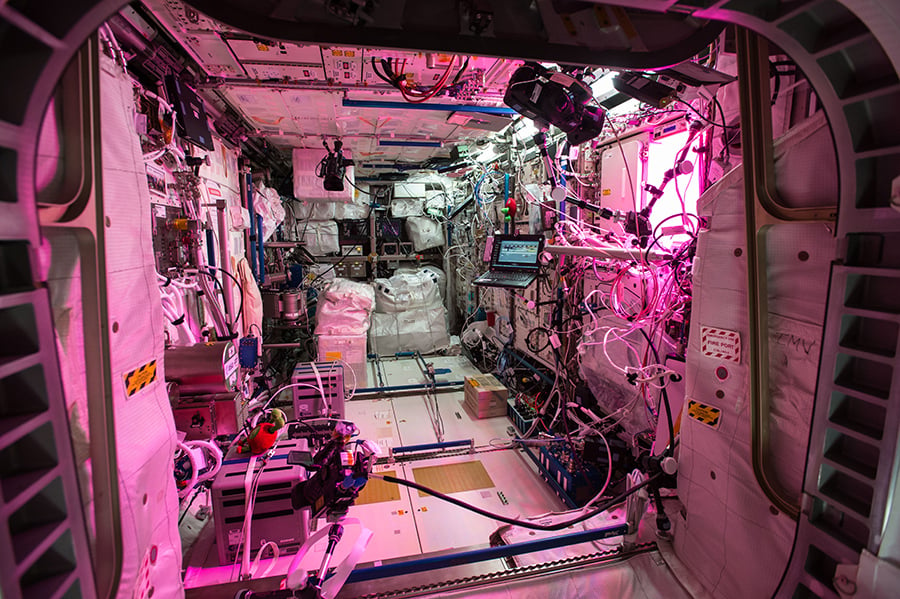

The interior design of the International Space Station takes a back seat to technology—the opposite of the majestic and immaculate spacecraft you see in sci-fi blockbusters.

This article is part of the “tech x interiors” special section that was guest-edited by the design firm Studio O+A. The section, which appeared in the April 2018 issue of Metropolis Magazine, explores how technology is reshaping the workplace. You can find the full section online here.

2018 marks the 20th anniversary of the start of construction of the International Space Station. The first segment of it was launched in December 1998 to a target point in an orbit about 250 miles above the earth. Arriving a few days after launch, that first section—a self-propelled spacecraft module—set the scene for a 12-year construction program that saw the assembly of 33 more major pieces delivered mostly by the space shuttle. Building sites often have accidents, but there were no mishaps plugging the station together in space. It was an astonishing success story given the multitude of hazards involved.

Berthed, bolted, and wired together, the 34 pieces have metamorphosed into a genuine extraterrestrial human settlement. Succeeding Mir, the Russian space station that orbited the earth from 1986 to 2001, the International Space Station has accommodated during its first two decades a community of 230 astronauts, cosmonauts, and deep-pocketed space tourists. By comparison, around 100 explorers established the Jamestown colony in Virginia in 1607.

Whether arriving by square-rigged ship or spacecraft, settlers bring with them few creature comforts, as stowage room is limited and the essentials matter most. In the station, crews are sealed inside a cluster of pressurized cylindrical modules stuffed with vital hardware and consumables. The architecture is austere, so much so that former astronaut Chris Hadfield likened the module interiors to hospital corridors. (Early designs from the 1980s that attempted to enliven and enrich the interiors were ultimately overruled by engineering priorities.) Banks of racks full of equipment and experiments line the curved walls of the modules, leaving narrow corridors down the center for crew access and movement. Familiar floor, wall, and ceiling surfaces dissolve to become rows of confining rack faces. These are often cluttered with switches, sockets, cables, monitors, laptops, checklists, and other paraphernalia that protrude into the corridors, giving them a shambolic appearance.

The lack of architectural contrast between these surfaces produces a psychological effect: Up and down can be switched in the minds of crew members floating weightlessly through the modules. Known as the visual reorientation illusion, this phenomenon can cause disorientation, confusion, and nausea. Crews combat this by using lines of lighting, end-hatch shapes, information signs, and labeling as visual cues to create the sense of a floor reference plane.

There are no traditional work areas in the station. During the workday, crew members in the laboratory modules move from one rack face to another to tend to experiments and enter or retrieve data. Guiding them are daily timelines called radiograms sent up by ground controllers. These tell each crew member precisely what he or she has to do throughout the day, planned down to five-minute increments.

The station was originally meant to include a habitation module for leisure and sleep. Specified as a major module throughout the design phases, it was canceled, half built, in an emergency budget reduction in 2001. Scrapped were a proper wardroom and galley for preparing food. As a substitute, one of the Russian modules has an ungainly contraption that approximates a giant foldout seat tray on a commercial aircraft and is the closest the station gets to having a dining table. This projects into the corridor, and the crew gathers around it for communal meals. Breakfast, lunch, and dinner typically involve opening tin cans and plastic pouches and spooning the sometimes-rehydrated food directly into the mouth. Much of the food has the consistency of sticky paste to stop it from floating away. Needless to say, mealtime does not approach the elegantly prepared dinners that Dave Bowman and Frank Poole order from the galley of their spaceship bound for Jupiter in Stanley Kubrick’s iconic 1968 movie, 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The interior architecture, though, is not spartan in all places. The rack frameworks are roughly the size of passport-photograph booths and were large enough to adapt to private sleeping compartments with comfortable sleep restraints (the term for space beds) and storage for clothing and personal effects. One of the station’s smaller node modules has become a dormitory containing four sleeping compartments. There is also a refuge where crew members can go for some peace and quiet—a multi-windowed cupola that arrived near the end of the station’s assembly sequence. Unlike ornate cupolas perched on the tops of domes and roofs, this one is mounted on the station’s underside and offers stunning panoramas of the earth’s surface. It has become the favorite place for off-duty crew members to go with a guitar, a book, or a camera.

Twenty years on, the International Space Station has become one of the world’s leading scientific laboratories. It has supported experiments that now number in the thousands and range from health, education, and technological innovation to earth monitoring, disaster response, and economic development. In the field of health alone, emergent research spans wound healing, cancer diagnosis, eye surgery, stress monitoring, ultrasound technology, asthma relief, medicine for the elderly, shingles detection, immunology, cardiology, sleep quality, and vestibular balance, to name a few.

Scientific research needs time and care to get results, as decades of studies devoted to fighting cancer bear witness. The more time and care expended, the better the results—and that is why every extra year the station spends on research counts. Stretching out its life may make a difference in discoveries and treatments that could overcome some of the world’s worst diseases and other challenges. The station’s international partners have agreed to back it until 2024, but beyond that its future is uncertain. At some point, the effects of wear and tear may begin to render it unsafe without a refit. Upgrading, recycling, and repurposing make sense to enable the station to press on with its valuable research and help its partners recoup their huge investments in it. The first flight of SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy rocket in early February has unexpectedly boosted the station’s long-term prospects because of the rocket’s extremely low launch cost. The station’s next major anniversary could even be its 50th.

David Nixon is an architect who has specialized in the field of space exploration since the 1980s. He is the author of the book International Space Station: Architecture Beyond Earth (Circa Press).

You may also enjoy “Why Technology Can Be the Enemy of the Creative Workplace.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025