March 15, 2021

An Exhibition Celebrates 50 Years of the Japan Society Building and Centuries of Craftsmanship

When Practice Becomes Form: Carpentry Tools from Japan showcases the invisible structures that underlie traditional building.

The first thing a visitor encounters upon entering When Practice Becomes Form: Carpentry Tools from Japan at New York City’s Japan Society, is the faint aroma of sawdust. A combination of cypress and cedar, this subtle scent pervades three halls filled with building models, traditional hand tools, and joinery displays, reinforcing the fact that the root of traditional Japanese building is the tree.

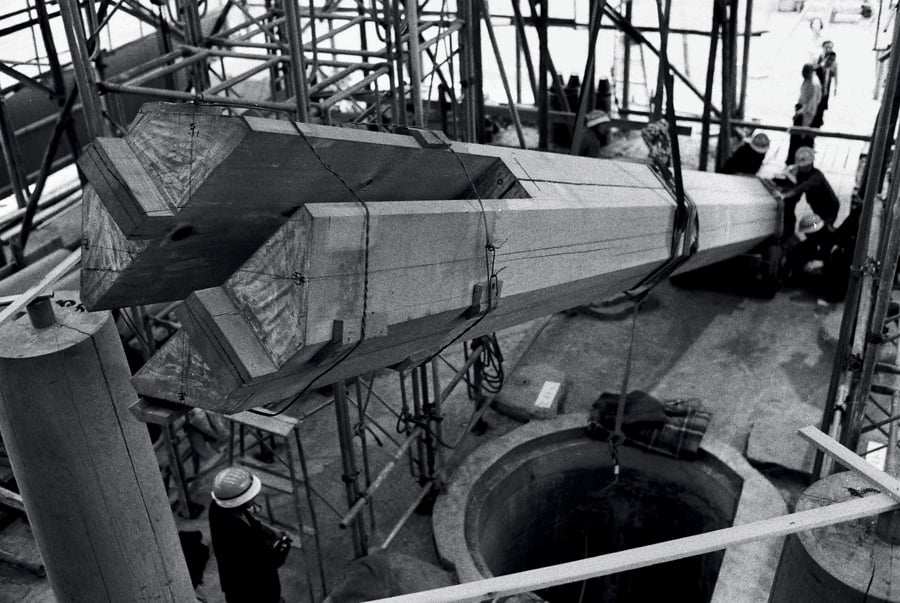

Plentiful in that heavily forested archipelago, timber was the material of choice for the everyday architecture of dwellings and shops as well as for sacred spaces such as of temples and shrines, though the show focuses on the design, construction, and preservation of large temple buildings. Everything in this exhibition, from ceiling height models detailing the design of bridges and roofs to an extensive selection of hand saws, chisels, and planes, is in some way an homage to this primeval building material.

Organized by Japan Society in collaboration with Takenaka Carpentry Tools Museum, and designed by Sou Fujimoto with Popular Architecture, the exhibition is the institution’s first show since closing last spring due COVID-19 restrictions and celebrates the 50th anniversary of the society’s Junzo Yoshimura–designed building on East 47th street in Manhattan.

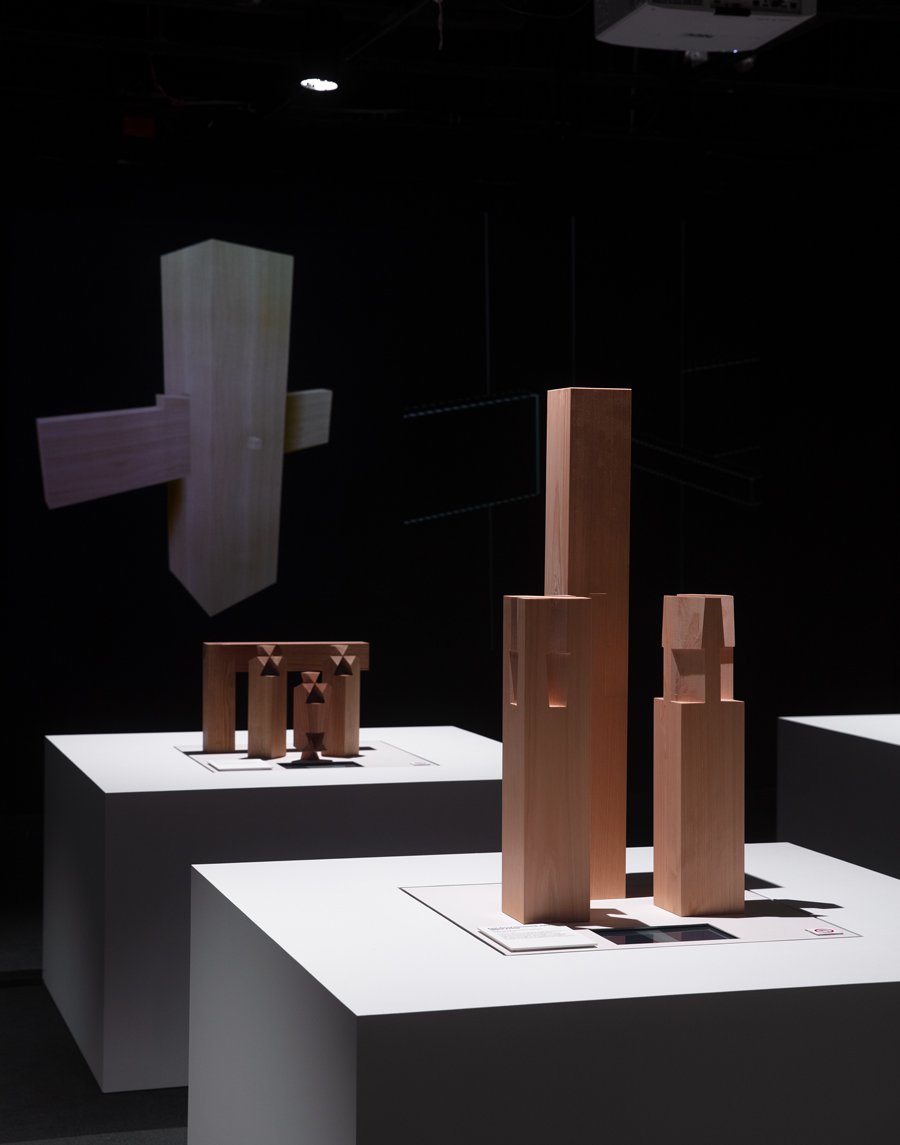

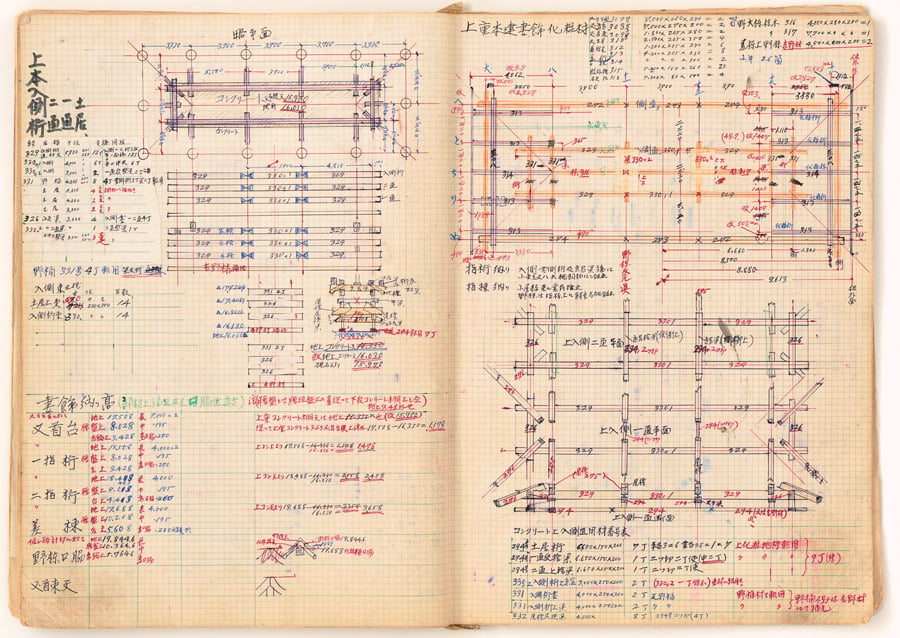

In the first gallery, visitors encounter a row of wooden models for roof sections of Buddhist temples that show in detail how painstakingly Japanese master carpenters or tōryō, would create complex brackets and roof assemblies out of relatively simple pieces that could be cut and carved by hand. Hung along either wall, as though they are still in a carpenter’s woodshop, are scores of full-scale wooden stencils that would have been used to create curves, ornamentation, and other details onto blocks of rough-hewn lumber.

Yukie Kamiya, director of the Japan Society Gallery, says that the aim of the exhibition is to “unveil ‘invisible’ structures under the beautiful surface of the wooden architecture.” The largest gallery is dedicated to the heart of Japanese woodworking, the incredible array of joints, called kigumi, which artisans developed over hundreds of years. On a series of plinths, models show how the wood is carved to reveal the mortises, tenons, dovetails, goosenecks, scarf joints, rabbets, and other types of joints that hold together ancient buildings.

Refined over centuries from simple lashings and notches to extraordinarily complex joints that puzzled historians until recently, they show the power of design to transform simple logs into delicate, yet resilient architecture. Kamiya explains that the wooden joints absorb the shock of earthquakes and are replaceable and repairable by future generations, allowing Japan’s monumental wooden buildings to stand for centuries.

The tools that carpenters would have used to create such structures as the Kintai-kyō Bridge in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture, a model of which looms large at the end of the first gallery, are on display in an adjacent room. On loan from the Takenaka Carpentry Tools Museum in Kobe, Japan, it’s these instruments that tell the craft’s story. Without power tools or plentiful metal fasteners such as nails and screws, traditional Japanese carpenters had to work with the wood itself using saws and chisels to create complex and durable joinery. Rough cutting with hand saws, cutting out mortises with chisels, smoothing beams with hand planes, cutting details with carving chisels, selecting wood from a handful of species common in Japan, the exhibition makes clear that theirs was an expertise hard won through arduous and constant practice.

Though architecture has changed and materials such as steel and concrete have in many ways obviated the need for labor intensive joinery, exhibition architect Sou Fujimoto thinks that contemporary practitioners should take note. “I hope one can see how natural materials and man-made items can live together. We can create much from these fundamental basics,” he says.

You may also enjoy “A Jewelry Exhibition in Antwerp Channels Space Age Aesthetics”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025