November 25, 2019

An Artist Re-thinks Museum Architecture’s Impact

Lauren Henkin installs sculpture at the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati in order to question the sites reserved—and not reserved—for art.

The unveiling of Cincinnati Arts Center’s Zaha Hadid–designed building in 2003 broke ground on several fronts: It was the first museum project helmed by a woman architect in the United States, and Hadid’s first stateside project. The construction, as well, marked an American iteration of the “Bilbao effect,” turning attention to a small Midwestern city through a fete of high-end art and architecture. The $27.5 million tour-de-force conveyed Hadid at full capacity: It was a masterful orchestration of the mundane and sublime within a body that is at once welcoming and overpowering, with 16,000 square-feet of space dedicated for exhibitions in Cincinnati’s downtown.

The late starchitect’s signature traits—eye-catching façades and swift marriages of sharp and smooth walls—prevail across the building; however, Hadid’s most evident gesture in the Cincinnati Art Center spills outside, in a fashion she called “urban carpet.” Letting the lobby’s voluptuously curved interior wall extend into sidewalk, Hadid aimed to bridge the art inside with life outside, connecting the public to an encounter that, at other museums, can be intimidating and uninviting. When artist Lauren Henkin learned that three concrete markers standing on Hadid’s curved “urban carpet” aimed to keep skateboarders at bay, she also took note of a single stanchion placed inside, on the other side of the museum window, seemingly without any purpose. Her curiosity led to Prop 2, one of eight sculptural interventions the Maine-based artist installed at Hadid’s architectural artwork this month. The artist added seven other similar concrete forms next the lone-standing stool inside in order to “complete an idea that morphs into its final stage.”

These pieces, which Henkin commissioned from local fabrication studios, are all a part of her latest exhibition, which opened November 22 and runs until March at the museum. Titled Props, the show deploys industrial materials commonly used in construction, such as concrete, steel, and PVC, and activates areas of the museum that previously sat dormant, unusable for the exhibition of art. “During my studies, the emphasis was on conceptual ideas, around architecture being sculptural, rather than concerns with where bathrooms should be,” the artist tells Metropolis. In Cincinnati, Hadid’s medley of exhibition and operational sites in the museum prompted Henkin, who studied architecture at the Washington University at St. Louis, to think about how art and architecture can challenge and compliment each other, while the public, as viewers of art, navigate these two omnipresent visual forces.

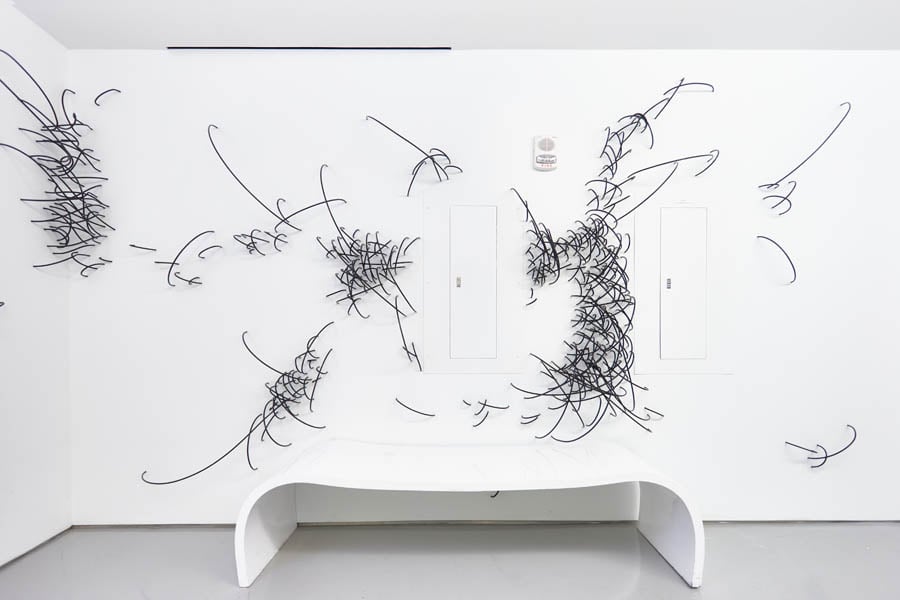

“The project challenges the idea of where to expect to find art in a museum, while incorporating the museum itself,” says the artist, who intentionally placed art in spaces used for circulation, public engagement, and even restrooms. Henkin’s interventions both beautify and critique the building’s various architectural forms—what the artist describes as “breaking down the building’s formality.” Hadid’s presence is arguably most evident in the long, black steel staircase that guides visitors towards exhibition floors, and the artist’s gesture over Hadid’s here is Prop 5, a dramatic arrangement of wooden beams and plaques that seem on the verge of collapse, contrasting with the rigid and sure formation of their surroundings. Prop 6 is jumble of double-sided mirrors Henkin placed on an angled middle ceiling, only visible from two stairwell landings. The reflective quality of the mirrors creates opportunities for viewers to communicate with both the space and the work—“with and against Hadid’s concept,” according to the artist.

When it came to placing work in bathrooms, Henkin—a female artist—had thought she would be limited to the women’s restroom. When exhibition curator Steven Matijcio offered her the opportunity to step into the men’s, she decided to interject an organic and “feminine-looking” aluminum and polyacrylic honeycomb sculpture, Prop 8, to subvert the room’s stark and clinical atmosphere. Inside the women’s room, a grid of PVC pipes, Prop 4, hangs on a blank white wall that both echoes a pristine gallery corner and an ongoing construction, merging industrial minimalism with sleek exhibition design.

In a building Hadid described as “labyrinthine complexity of spatial composition,” Henkin attempts to celebrate and shake the structure’s complexities through the heft of sculpture and subtlety of art. And in doing so, she engages her audience in an act of architectural interaction: “Activating these spaces beyond their intentions gave me an opportunity,” she says, “to challenge myself as an architecture-trained artist at a museum with incredibly persuasive architecture.”

You may also enjoy “Appalachian Makers Tell Their Own Story in a New Exhibit.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025