February 11, 2022

A New Book Explores the Understated Career of Filipino Architect Leandro Locsin

Locsin’s position as effective court architect to the Marcos family meant he didn’t lack funds for his best-known projects but, fortunately, even infamous kleptocrats Ferdinand and Imelda could not easily pocket a convention center. Girard surveys some 200 Locsin projects as well as various unrealized plans in a mostly-chronological, partly-typological account of the many phases of Locsin’s career, including numerous offices, hotels, churches, residences, the fantastic Expo 70 Philippines Pavilion in Osaka, and the 1,800-room palace (you read that right) of the Sultan of Brunei.

While most Filipino architects of the era were educated in Europe or the United States, Locsin studied at De La Salle College in Manila. His work was a deliberate turn from Spanish and American colonial neoclassicism, following a familiar trajectory of nation-building through modernism (see Brazil, Turkey, and many more). Other influences began to appear in the late 1950s, from traditional and modern Japanese architecture to Paul Rudolph, Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as local Philippine methods and forms. He attested, “I believe that one would do well to look back once in a while to see what we had—not in order to return to it but to make use of it to create something new.”

Concrete was obviously the favorite son, and he put him to work in various ways from using prefabricated and in situ concrete in the same projects, to concealing or dramatizing joinery, to pouring it thick and thin (one local and very clever expedient was replacing some steel rebar with bamboo to enable lighter slabs). He was not hung up on structural honesty and inserted hollow piers and columns when he pleased. His material palette expanded rather than contracted with time, eventually turning to wood and various masonry elements.

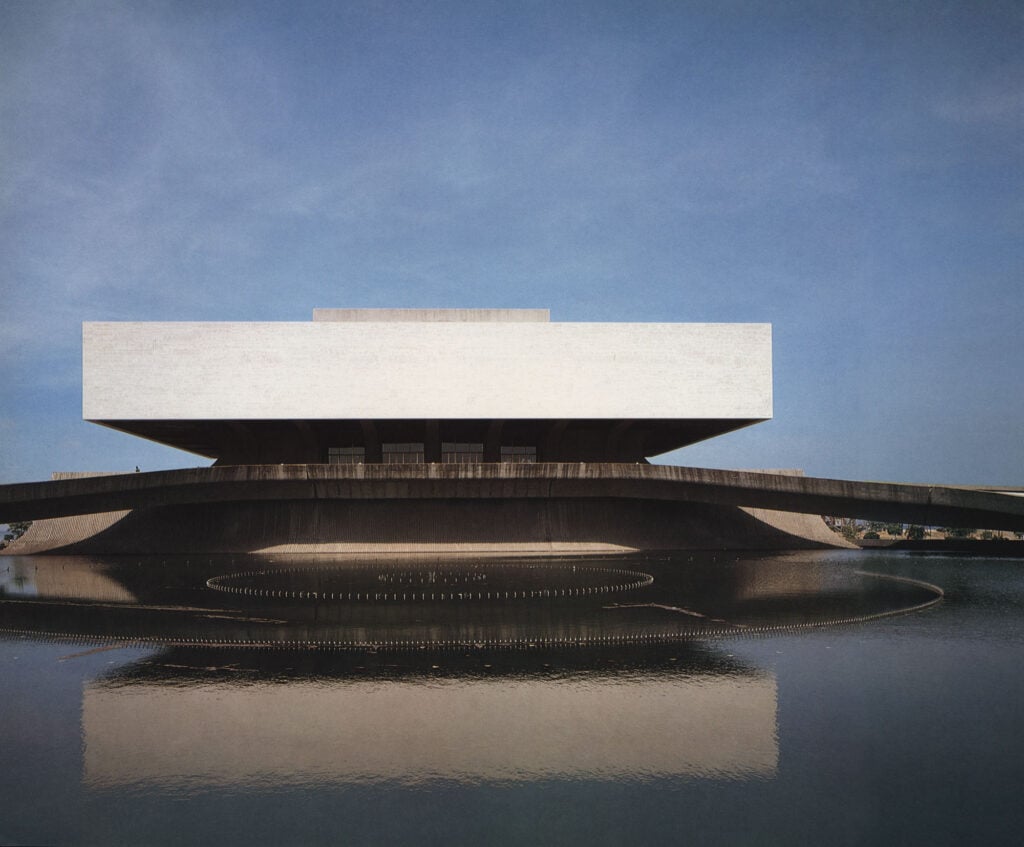

Blocky concrete defined the exteriors even in his largest projects, but upon entrance, these gnostic gigantisms revealed human qualities. The entrance hall of the Philippine International Convention Center is particularly dazzling, shaped by curvy bush-hammered concrete parapets and stairways, Rudolphian red carpeting, and a dazzling lighting scheme made up of over 3,000 bronze tube-borne bulbs. Girard explains, “The majority of these are at a constant height close to the ceiling, but three separate groups descend to different heights to delimit particular areas, like giant chandeliers. The opposition between the sculpted mineral elements and the luminous metal rods completely breaks up the space, which seems to have no upper limit and to be connected to the cosmos.”

Closer to those cosmos, Girard deftly accounts for Locsin’s handling of roofs, the vital feature in architecture for a country dealing with considerable heat and rainfall. His roof variations are endless and surprising, keeping the rain out and allowing the breeze in but shifting with creative whim otherwise. His deep facades alone could sustain a monograph, with countless intriguing colonnades and sunshades. Many of his buildings also skillfully conceal multiple independent load-bearing elements, a critical component to reducing earthquake damage.

It’s a body of work that demands attention and is assuredly unique. As Girard writes, “Leandro Locsin had the ability to integrate different parameters, whether from the vernacular or from modern architecture, and succeeded in synthesizing them by transforming and adapting them to his needs.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Recent

Profiles

BLDUS Brings a ‘Farm-to-Shelter’ Approach to American Design

The Washington D.C.–based firm BLDUS is imagining a new American vernacular through natural materials and thoughtful placemaking.

Projects

MAD Architects’ FENIX is the World’s First Art Museum Dedicated to Migration

Located in Rotterdam, FENIX is also the Beijing-based firm’s first European museum project.

Products

Discover the Winners of the METROPOLISLikes 2025 Awards

This year’s product releases at NeoCon and Design Days signal a transformation in interior design.