September 1, 2022

At Europe’s Oldest Design Biennial, A Socially Committed Approach to Design Stands the Test of Time

In 2014, MAO’s team trusted curator Jan Boelen with that task. The biennial’s 24th edition and 50th anniversary edition held that year, called BIO 50 – 3, 2, 1… TEST, gathered 11 international design teams in Ljubljana to address how design impacts everyday live in Slovenia (I took part in one of those teams). In 2017, as Brendan Cormier detailed in his BIO 25 review in this publication, under the title Faraway, So Close, curators Angela Rui and Maja Vardjan invited six pairs of international designers and Slovenian experts to explore the country’s urban/rural divide. In 2019, BIO 26 – Common Knowledge, curated by Thomas Geisler and Aline Lara Rezende, six multidisciplinary teams addressed how knowledge production and transmission takes place in Slovenian institutions

The 2022 edition, BIO 27 – Supervernaculars, curated by Jane Withers and Ria Hawthorn, builds on this collaborative, propositional model. Under the motto Design for a Regenerative Future, this year’s biennial is grounded on five commissions developed by local production platforms in collaboration with international mentors. At BIO’s opening last May, Withers claimed this platform model aims to “avoid the kind of circus-that-comes-to-town kind of biennial,” instead, it directs resources and attention towards original, locally critical actions.

Grains for Brains, developed by the Robida collective based in the Alpine village of Topolò and mentored by designer Carolien Niebling, addresses the uses of buckwheat, a largely forgotten staple of the traditional local diet. Designing a BioVernacular, developed by the Pjorkkala collective and mentored by architect Shneel Malik, proposes a system of 3D-printed ceramic water filters to purify the well water consumed by those unconnected to a public water supply—a population that includes a fifth of Slovenia’s two million inhabitants. Communicating Modern Architecture, developed by the interdisciplinary group Garnitura and mentored by architecture researcher Adam Štěch, offers a new perspective into the architectural legacy of Jože Plečnik. The Futuring collective, mentored by designer and sustainability expert Sophie Thomas, developed Regenerative Cultural Production, an environmental audit of BIO 27 that is also a digital, open-source, open-ended toolkit aimed at helping cultural institutions acknowledge and mitigate their environmental impact. Forbidden Vernaculars, developed by the Krater collective and mentored by Atelier LUMA and BC Materials, embraces rammed earth architecture as a form of enquiry into the potential and limitations of vernacular building techniques in our hyper-regulated times.

BIO 27’s main exhibition provides context to these outcomes by showing artifacts and initiatives from a wide range of sources, disciplines, scales, and times arranged in four thematic sections: Forgotten Vernaculars, Negotiating Traditions, Reimagining Systems and Infrastructures, and Catalyzing Community. Adopting the vernacular as a framework to reflect on the transmission of knowledge, Withers and Hawthorn present these instances of design not as works or props to be contemplated, but as tools meant to be used. As such they drive the appreciation of design away from novelty, authorship, or expertise and towards purpose, collaboration, and community. This makes BIO 27 a hopeful, empowering exhibition. Yet it could be bolder by critically addressing how design and architecture professionals’ approaches to vernacular expressions often betray unequal, even predatory power relations between urban and rural, erudite and popular, empire and colony, center and periphery. Such power relations are, as Vida Rucli of Robida commented on a panel discussion during BIO 27’s opening, embedded in the very term vernaculus, Latin for domestic or native, which derives from verna, a slave born in the house.

The work conducted by the biennial’s production platforms nevertheless questions power relations between rulers and citizens. By developing processes and projects that defy tradition, convention, and legislation these platforms advocate for a socially committed and emancipatory design practice. When doing so within a cultural institution— and not, say, within industry or academia— they question what we mean by the production of knowledge but also of content, value, and wealth. But as the designer and co-founder of the Krater collective, Gaja Mežnarič Osole, comments, because they work on the margins of design practice, these production platforms are hardly sustainable financially. In the context of the biennial, they are supported by the Centre for Creativity, an interdisciplinary platform established in 2017 at MAO to finance and promote Slovenia’s cultural and creative sector. Yet the kind of funding required for their participatory, long-term, open-ended design processes developed in the institutional gray area BIO has successfully created is hard to find.

The kind of innovative design research presented in biennials and other exhibitions has in the twenty-first century often been supported—especially in Europe—by research grants and cultural subsidies, as well as the commercial design-art gallery circuit, with varying effects on its process and appreciation. More recently, the New European Bauhaus, a major initiative launched by the European Commission in 2020, may provide a relevant opportunity for such platforms: Its prize, of which Krater was a finalist this year, distinguishes exactly the kind of design practice BIO’s model advocates. It is but one sign that BIO, which in 2024 will celebrate its 28th edition and a decade of its original mode will, in spite of its limitations, withstand the test of time.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

The Project That Remade Atlanta Is Still a Work in Progress

Atlanta’s Beltline becomes a transformative force—but as debates over transit and displacement grow, its future remains uncertain.

Profiles

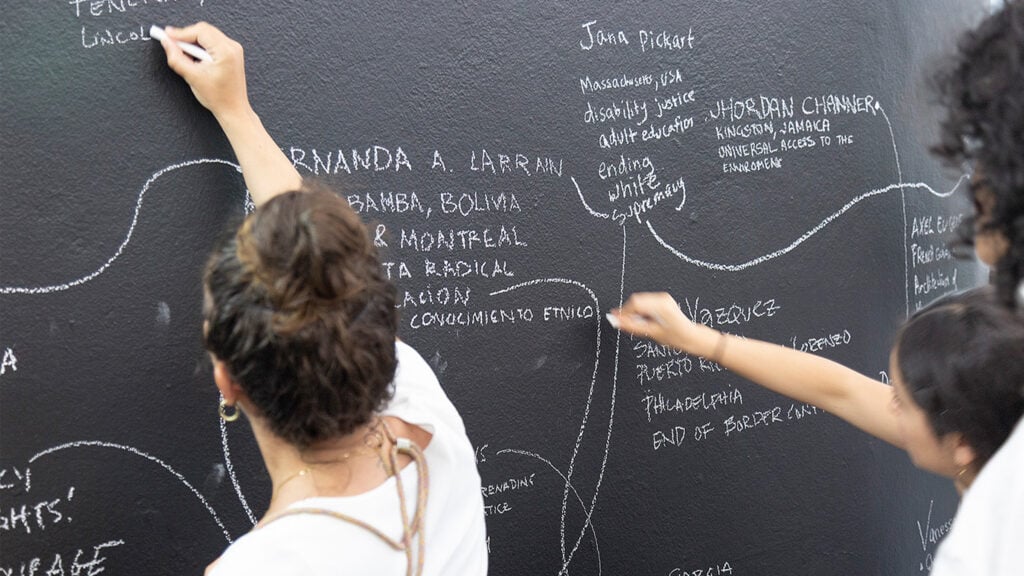

WAI Architecture Think Tank Approaches Practice as Pedagogy

Nathalie Frankowski and Cruz García use their practice to help dismantle oppressive systems, forge resistance spaces, and reimagine collective futures.

Products

Functional Beauty: Hardware That Does More Than Look Good

Discover new standout pieces that marry form and function, offering both visual appeal and everyday practicality.