January 14, 2021

Memorials Are for the Living

Eddie Blake and Gian Luca Amadei question how architecture can help us contemplate loss and memory in the age of COVID-19.

Memorials aren’t for the dead; they are for those still living. As episodes of remembrance, they also inform new memory, reversing the way we think about time: instead of the past forming the present, the act of memorialization shapes history and thus how we access the past. But how do we create memorials when those who are left behind agree on so little? For centuries, architects have had to engage with the contentious issue of who gets remembered, and we live in an era where narratives are more widely contested than ever.

In the past, architecture has articulated a mainstream narrative about how a society or nation saw an historic episode. Sir Edwin Lutyens for the British Imperial War Graves Commission after the First World War tackled the problem through formal abstraction, avoiding religious connotations. Maya Lin famously set out the names of the dead chronologically avoiding any discrimination between rank, religion or class at the Vietnam War Memorial. As Mies Van der Rohe wrote in Architecture and the Times: “Architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space.” If this is true, we might divine the will of our current moment by looking at the memorials we erect after the pandemic ends.

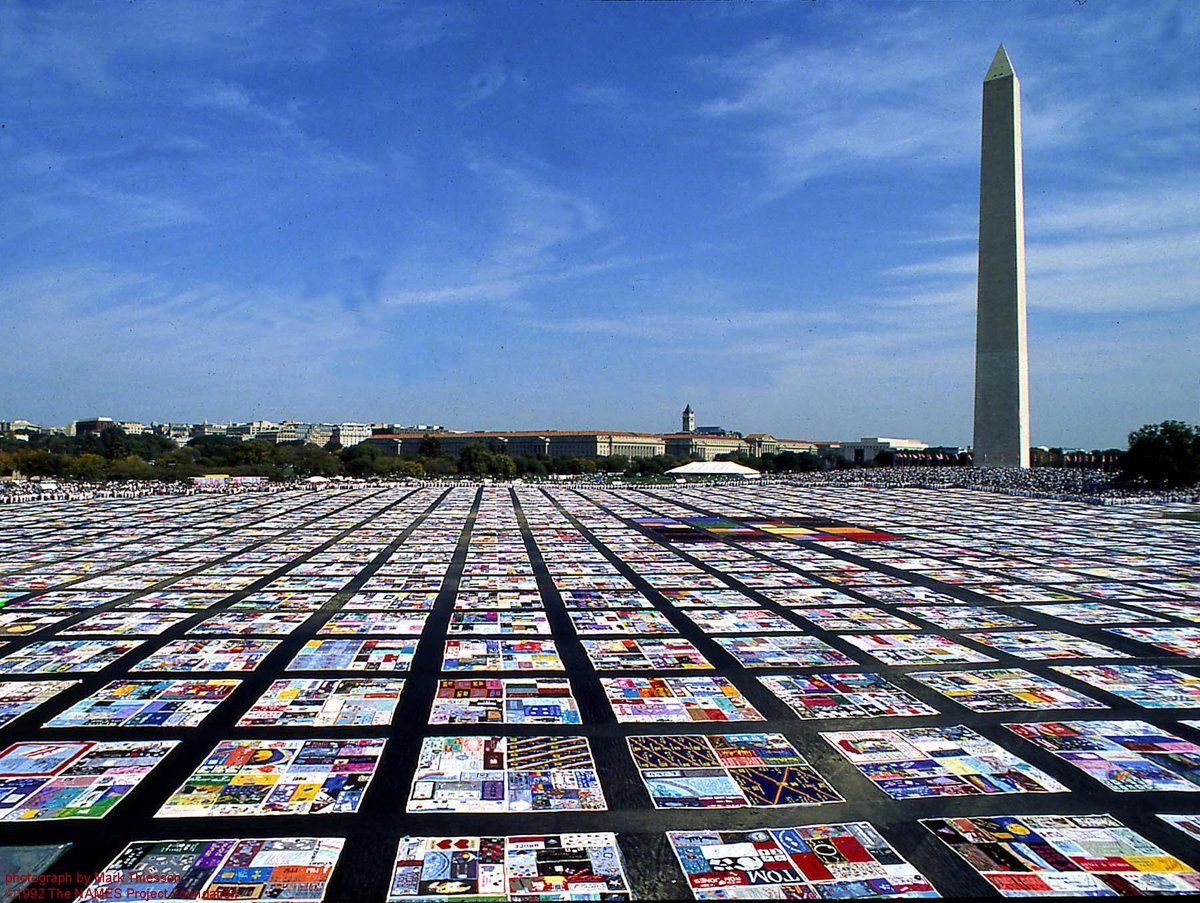

Since the 1990s’ new forms of memorialization have challenged the traditional formats and aesthetics associated with memorials; the obelisk, the broken column, the carved stone wreath, are rarely seen in public memorials, although still used to some extent in private contexts. More significantly, the type of memorial is shifting, from objects in space, to spaces that can be occupied – The Princess Diana Memorial Fountain is a good example of a memorial as space, in this instance designed to be played in, by children. These new forms attempt to address the complex nature of memorials today. Another example, the AIDS Quilts memorial, made of 54 tons of hand-made quilts, speaks of both the individual and collective effort to keep alive the memory of AIDS victims. Although this memorial is not a building, its physicality has a spatial presence that is both esoteric and tangible. This project is monumental not only because of the astonishing number of quilts, but also because of the length of time it took to be realized in its entirety (35 years). Another good example of participatory memorialization is the Harburg Monument Against Fascism, erected by the City Council of Harburg amidst a rise in neo-nazism. A solitary obelisk, it’s three feet by three feet square extruded 36 feet high, clad in lead, and looks overwhelmingly solemn viewed from a distance. Local citizens were invited to inscribe the lead, creating a shared message that was both heterogeneous and unified.

A contemporary experiment in memorialization, The Gun Violence Memorial Project, was launched at the 2019 Chicago Architecture Biennial. The exhibition consists of model houses, built of glass bricks. Each brick represents one of the lives lost to gun violence each week in America, 700 bricks, 700 lives every week. Families who have lost a loved one to gun violence contributed remembrance objects, which are placed within a glass brick, displaying the name, year of birth, and year of death of the person being honored. In this case architecture provides the aesthetic envelope for the project, in the shape of the archetypal pitched roof house. Its interior is visible from the exterior, as a metaphor that is expressive of domestic gun violence but also of segregation and social division. The Gun Violence Memorial is not a memorial in which architecture is abstracted to represent an idealized form of memorialization, but one in which architecture itself is at the service of the project and the people. In this respect architecture mediates between the private experience of loss and the context of public space.

We order our chaotic feelings about oblivion through the architecture of death, from road-side tributes, to tombs, cenotaphs, memorials, monuments, graves, urns, crematoria and coffins. In these designed objects we find the real record of life as represented by architecture. Memorials are a last stand against entropy, holding back the bleak, disinterested chaos. They are a testimony that life has meaning.

Memory is re-inscribed by repetition. So having a site for memorialization, which can be returned to, is important. People can go there, but also know it is there, as a repository even when no one is present. Each visit is an emotional investment, and memorials require that investment — to mean anything, they have to mean something to those who will stand in front of them. There is a dynamic relationship between object and viewer. Architecture can’t just be designed to embody people’s memories or feelings — the intended audience has to allocate emotional energy to the object for it to become a memorial. Without this the architecture has no more value than the material and labor it took to build it.

Of course, it’s rarely the dead who decide how they are remembered, typically the family, a committee, or the state make those decisions. As a result the memorial is always an expression of a relationship between the living and the dead given material form by architecture. The new mass/social media-saturated grief and loss with its diffuse stories and multiple viewpoints means that articulating that relationship is all the more complicated, but still architecture may well be the medium best suited to the task. “Liberated from the obligation to construct, architecture can become a way of thinking about anything – a discipline that represents relationships, proportions, connections, effects, the diagram of everything,” wrote Rem Koolhaas in 2005. Put another way, once we escape the dreary reality of keeping the rain out, architecture perhaps becomes the ultimate way to represent relationships.

So how can architecture contain the inexpressible? In a very basic sense, it is simply by being bigger than human, amounting to something more than an individual could ever be. Because of its scale, architecture almost always represents a collective effort, even if the reward for that effort is rarely equitably distributed. In this sense it is greater than the sum of its parts. Architecture can also express unity and solidity—It is this quality that gives the potential for gathering diverse personal narratives and perhaps in some small way it might resolve life’s inequalities, through reconciling the individual with the collective. If death is the great leveler, then so too can be the architecture of death. Memorials can be the opposite of all human bodies; perfect and unchanging. When we design for death, what we’re really designing is an idealized form of life. In this way memorials can express something like immortality. They don’t offer a substitute for lives that are lost, but they can represent all the qualities we are missing.

You may also enjoy “This Concept for a COVID-19 Memorial Builds a Stronger Community”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.