April 4, 2016

Review: MIT Publications Tackle the Future of Infrastructural Innovation

Twin volumes from MIT’s Center for Advanced Urbanism explore the cultural implications of infrastructure.

Rebuild by Design, bird’s-eye view of the New Meadowlands project, with Manhattan on the east.

Image courtesy MIT CAU + ZUS + Urbanisten, 2014

In January, MIT’s Center for Advanced Urbanism (CAU) released two books, Infrastructural Monument and Scaling Infrastructure (Princeton Architectural Press), detailing the proceedings from two infrastructure-themed conferences that took place in the Springs of 2013 and 2014 (respectively). The conferences brought together leading architects, policy makers, civil engineers, and other urban design practitioners to discuss important issues, ranging from transportation to disaster relief to policymaking. However, if global urbanism today marks the shift from Global North to Global South as the preeminent stage for urbanization, these books are inadequate representations of that pattern.

In one of the books’ more interesting transcriptions, Pierre Bélanger, landscape architect and professor at Harvard, tackles one of the most pressing challenges for contemporary urban planners: learning how to work with water. “Water,” Bélanger told the audience at Infrastructural Monument, “was the enemy of twentieth-century urbanization,” causing sewage and drainage problems, cholera outbreaks, and, of course, flood damage. It’s a consideration that has been largely omitted from historic civil engineering and urban design techniques, such as land reclamation, dams, dikes, and ditches. The general shift in urban planning today is to better tailor the built environment to the natural landscape. So, Bélanger proffered, one crucially important task for present and future urban designers is to rewrite the villainous role water has been assigned historically: “We must recognize that disasters of our making can be our undoing, and the real storm is us.”

In Scaling Infrastructure, engineer Adam Klapotcz presents the fascinating work of his company SenseFly, which produces drones that use high-resolution images to create two- and three-dimensional maps. His drones, which are inexpensive to produce and easy to use, make topographic models accessible to cities and towns—such as Tacloban, Philippines, and Fukushima Prefecture, Japan—with little or no basic infrastructure, or where infrastructure has been destroyed (no internet connection needed). The maps have enabled these communities to not only respond to disasters, but use data to plan their towns and cities for the short and long term.

Though Bélanger’s proposal for more flexible infrastructure is highly applicable (if necessarily so) in a global context, and Klapotcz’s drones can be–and are–used in “developing” cities in the Global South, the majority of the talks and essays collected in Infrastructural Monument and Scaling Infrastructure still focus heavily on infrastructural innovation as it applies to cities and regions in North America and Europe.

Various other initiatives and projects at the CAU are focused on regions of the Global South—in Bello, Colombia and Ghana, for example—and certain partner studios like the Resilient Cities Housing Initiative are focused on developing regions, yet neither conference emphasized scaling up in underserved regions. Alfredo Brillembourg, founder of Caracas-based Urban Think Tank and chair of architecture and urban design at ETH Zurich, was the only design professional, out of nearly 30 contributors featured in the two books, whose work makes notable reference to developing regions and cities. Furthermore, only Brillembourg, whose work focuses on improving living conditions in informal settlements in Caracas and elsewhere in Latin America, focuses in any significant way on the question of rights to the city, which he says have been “negated” by the “experiment” that has been the last two centuries of urban planning, design, and architecture. “We may be the last generation able to do anything about it,” he said at Scaling Infrastructure. “Our descendants will have the excuse of helplessness, but we have none.”

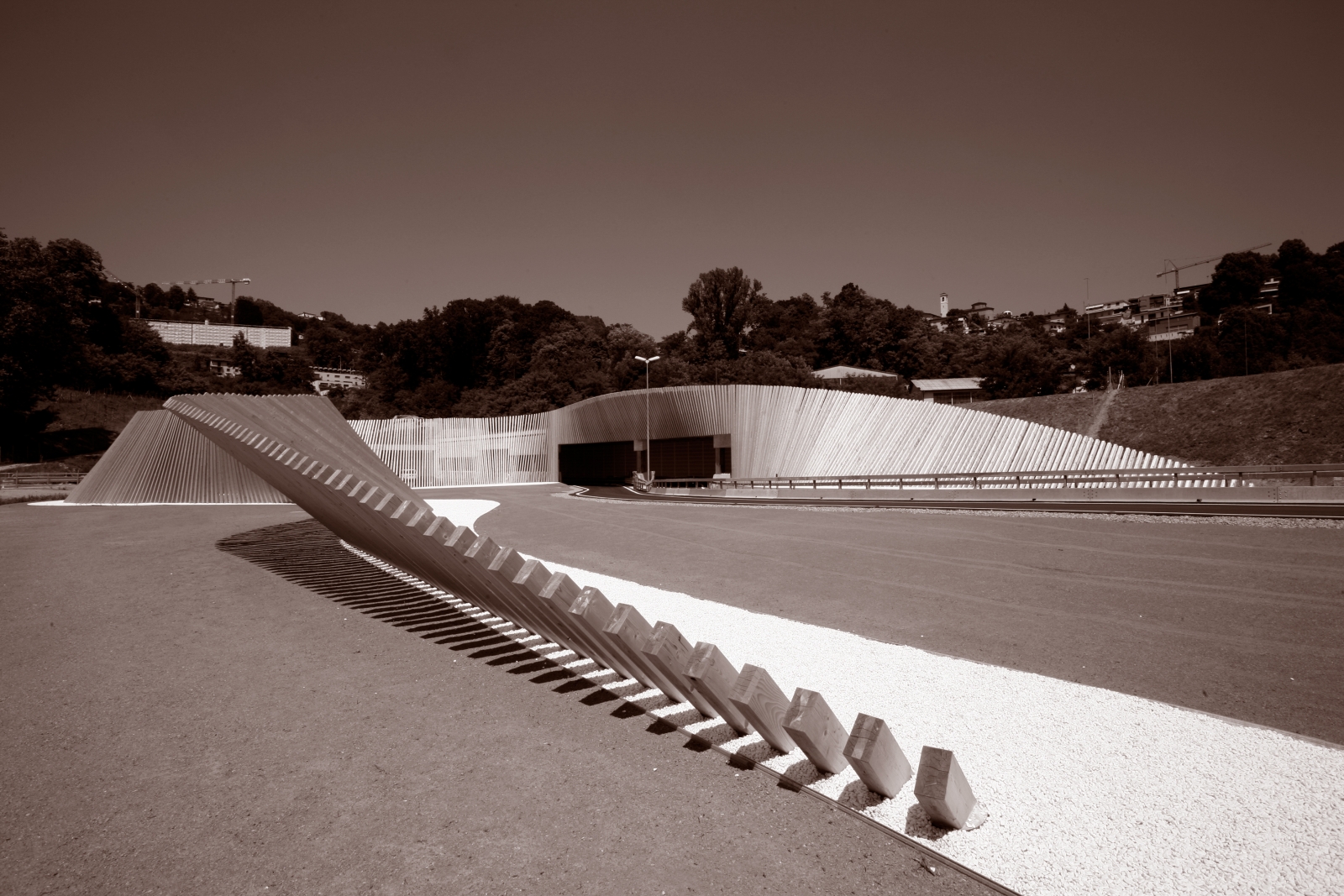

View of the entrance of the Gallery Vedeggino-Cassarate, Lugano, Switzerland, 2011-2012

Image courtesy Cino Zucci Architetti with Mauri & Banci SA, 2011-2012

Scheveningen Boulevard, The Hague, the Netherlands

Image courtesy Rosa Feliu

Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport. 2009

Image Courtesy Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport