December 11, 2015

Moshe Safdie and the World: New York Retrospective Finds the Architect Adopting a Global Perspective

An ongoing retrospective at New York’s National Gallery posits a new international focus for the architect’s work.

Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67, seen under construction with a crane positioning a prefabricated-concrete apartment unit into place

Courtesy Safdie Architects

At the unveiling of Habitat 67, Moshe Safdie was 29 years old, a mere lad in a profession dominated by men twice his age. The development, consisting of 357 prefabricated concrete boxes, sought to bring the pleasures of suburban living into a dense urban environment. In the process, Safdie, who was awarded the AIA Gold Medal prize this year, broke ground in at least three arenas: urban planning, domestic architecture, and prefabricated construction. Not bad, considering the project had grown directly out of his McGill master’s thesis.

In recent years, the architectural world has begun embracing with renewed interest the ideas Safdie first articulated in the 1960s, as a retrospective of his work at New York’s National Academy illustrates. Global Citizen: The Architecture of Moshe Safdie documents more than five decades of the architect’s work, beginning with his Habitat explorations and moving on to less ambitious but more prestigious projects, such as a national museum of the Sikh people in Punjab, India to Jerusalem’s Mamilla Alrov Center. Again and again, the show returns to themes that first took shape in Habitat 67: the desire to cultivate thriving communities while making often surprising connections between architecture and its urban, historical, cultural, and natural environments.

“The re-envisioned exhibition explores in particular what it means to create livable urban spaces, ” writes exhibition curator Donald Albrecht in the show’s catalog. Albrecht goes on to note how Safdie has again taken up that theme “with renewed vigor in today’s increasingly populous global cities.”

The retrospective’s latest iteration, which debuted in Ottawa in 2010, incorporates a new a section devoted to Safdie’s most recent work in Asia, including Sky Habitat. A kind of 21st-century version of the infamous Montreal complex, Sky Habitat consists of two 38-story ziggurat-like towers at the northern limits of Singapore’s urban core. Designed for Singapore’s upper-middle classes and wrapped in a glossy carapace, the project seems a far cry from Habitat 67, with that project’s Brutalist finishes and utopian goals of social inclusion.

Safdie revisited themes related to Habitat 67—prefabricated construction, dense living, generous amenities—in the speculative Habitat of the Future project (2013).

Courtesy Safdie Architects

Of course, the world has changed a lot since 1967. Public interest in and funding for high-quality affordable housing has languished. Even Habitat 67, built and owned by the Canadian government, has long since been privatized, with apartments typically selling well above Montreal’s average market prices. And Safdie’s own reputation as an architect has undergone several decades of stagnation, suffering from jibes ranging from corporate blandness to questionable taste.

Certainly Safdie’s latest residential skyscrapers provide bold challenges to the monolithic apartment blocks that tend to surround them. As Safdie told me during a walk-through of the show, Sky Habitat, like Habitat 67, “fractalizes the surface to open up as many points of interaction with the environment as possible.” Instead of mere views—the highest aspiration of most luxury high-rises (along with profit per-square foot)—Sky Habitat strives to connect each unit to the world in a way that goes beyond spectacle. According to Safdie, the twisting, stepped surfaces evolved not to draw attention to themselves, but to bring as much sky, air, and green spaces as possible into each individual unit.

Besides Sky Habitat, the exhibition’s final room includes Raffles City, a mega-development in Chongqing, China, and Jewel, a mixed-use project for Singapore’s Changi Airport. Slated for completion in 2018, the 1.4 million square-foot Jewel, with its massive, glass-encased hanging gardens, actually appears modest in scale when compared to Raffles City. With more than nine million square feet of offices, residential units, and hotels, the slender towers of Raffles City form an audaciously aerodynamic prow at the confluence of the Jialing and Yangtze Rivers. In classic Safdie fashion, the towers are knitted together by gardens at their base and, more boldly, by a 330-yard-long, glass-enclosed conservatory at the tower’s 45th floor.

Standing amid images of these glittery new works, Safdie related how his daughter, a committed leftist, ribs him about the kinds of luxury projects he is currently building. They are certainly a far cry from the publicly funded, morally ambitious Habitat 67, with its gritty, concrete finishes. And yet, nearly five decades after Montreal’s Expo 67, Safdie is still striving to merge two distinct typologies—the high-rise and the single-family house—in compelling ways.

Global Citizen: The Architecture of Moshe Safdie is on view at the National Academy through January 10, 2016.

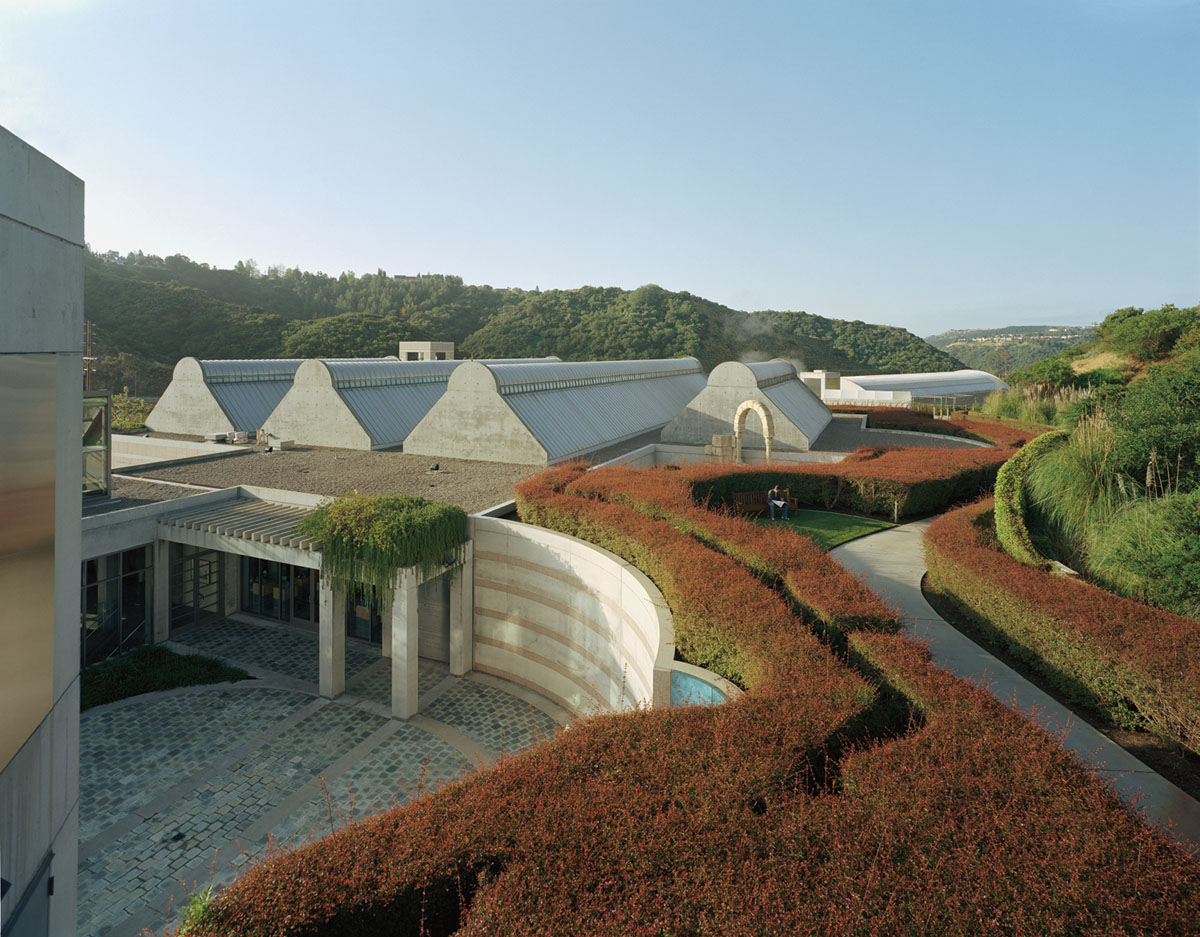

The Skirball Cultural Center (1996) in Los Angeles

Courtesy Timothy Hursley

Hebrew Union College (1988) in Jerusalem, Israel

Courtesy Michal Ronnen Safdie

Salt Lake City Public Library 2003

Courtesy Timothy Hursley

Yad Vashem Holocaust Museum (2005)

Courtesy Timothy Hursley

Marina Bay Sands resort (2010) in Singapore

Courtesy Timothy Hursley

Chongqing Chaotianmen mixed-use complex (2014) in Chongqing, China

Courtesy Safdie Architects

The Sky Habitat complex in Singapore will be completed next year.

Courtesy Neoscape/Safdie Architects

Jewel Changi Airport (2015)

Courtesy Safdie Architects

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025