April 29, 2021

From Victorian Gardens to Corporate Biophilia, Nature Inside Unearths a History of Interior Plantings

Despite differences in motivation, context, and aims, Penny Sparke shows that bringing flora inside stands as a token of unspoiled nature, a reminder of what’s gone.

Even the most casual observer knows that a central selling point of architecture has been making nature dramatically more visible. The trouble is that in looking out through the (ever-larger amounts) of glass at the forest, even erudite observers have tended to miss the plants already in the room. Miss Marple cracks the case in Murder at the Vicarage by noticing a potted plant that others had ignored. Penny Sparke, a professor of design history at Kingston University of London and author of several books, has accomplished similar sleuthing by examining objects in architecture and interiors’ plain sight. The tree has previously received its due only if carved and embalmed in varnish, Sparke argues, and plants have often been omitted entirely in the study of interiors, dismissed as evanescent afterthoughts.

The average person knows that we have brought plants inside for centuries but likely hasn’t given the matter much thought. Happily, Penny Sparke has, in her new book Nature Inside: Plants and Flowers in the Modern Interior (Yale University Press). The examples are as wide-ranging as a manor house orangery in 1750 and the Amazon Spheres in Seattle, but Sparke finds evidence of “continuity rather than disruption.” Plants inside—whether a handful on your mantle or forty thousand in the Amazon building—represent an abiding nostalgia for Eden, for the nature that we’ve bulldozed to put up whatever we are currently standing in. Whatever difference in scale, Sparke writes, “its roles as an aide-memoire of the pre-industrial past, as a form of therapy for human beings, and as an active agent in the creation of a non-toxic environment have arguably remained intact.” The rubrics under which plants are present in a space have been subtly different—at times spiritually inflected, at times justified as a health measure, other times aesthetically conceived—but they reliably stand as a token of unspoiled nature, a reminder of what’s gone.

A crucial point is the token. In no home or office is “nature” simply allowed to take its course; the word for that scheme is “abandoned.” Rather, there’s a great deal of work and aesthetic calculation in bringing nature inside: The plant becomes an object, valued as a symbol of nature but placed because it’s known to behave politely. The process of determining which plants wouldn’t overrun the whole solarium, flower obnoxiously, or die malodorously requires trial and error, and Sparke narrates many such experiments.

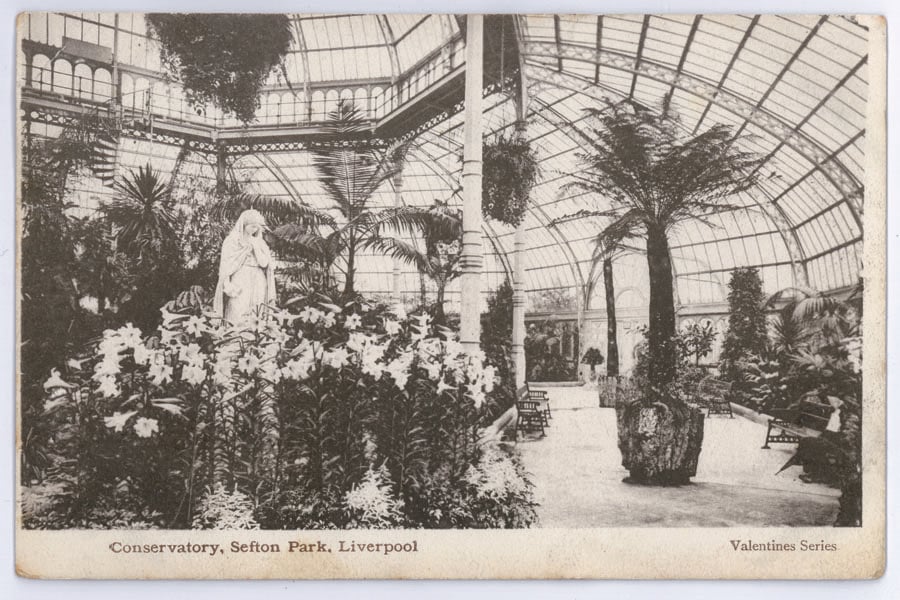

Early greenhouses, for example, weren’t indulgences but necessities, serving an essential new goal of sheltering plants from inhospitable climates. The impetus wasn’t decorative: The plants were useful for some other reason—medical or culinary or otherwise—but gradually, interior adornment grew more popular. This was a luxe sideline, confined to grand estates at first. With time they expanded to public conservatories and facilities such as the Crystal Palace before making their way to sunrooms in middle-class homes.

No plant’s natural habitat is a sitting room, and earlier interiors involved greater threats, requiring plants that could withstand gas light, coal dust, and worse. The durability of some species became gradually discovered, familiar because we’ve been growing them inside ever since. Aspidistra, dracaenas, rubber plants, palms, ferns, and cacti remain mainstays of interior planting.

One excellent chapter digs into the forgotten Victorian world of popular planting manuals, showcasing such enticing titles as Instructions in Gardening for Ladies, Webb’s Bulb Catalogue, Rustic Adornments for Homes of Taste, and Every Lady Her Own Flower Gardener. It’s a look into the genuine democratization of interior planting as an aesthetic realm, freighted varyingly with educational, spiritual, and health benefits. The idea that plants improved the quality of interior air preceded any evidence for the proposition, though it’s a hunch that hit the target. A consequence was that interior planting acquired strong gendered associations: When a sphere of female aesthetic agency emerged, it, of course, earned male dismissal as frivolous and emotional.

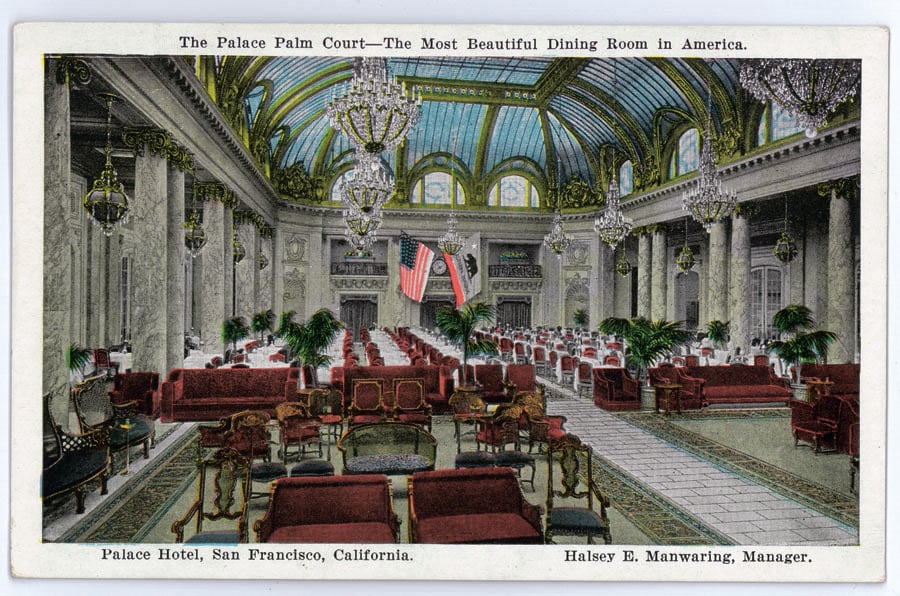

The middle and upper classes, increasingly likely to have plants at home, became accustomed to them when out: palm courts at many hotels, a winter garden in the SS Normandie, and even roses on the Graf Zeppelin. The botanical garden wasn’t always so dignified. Interior gardens played a bawdier role as vaudevillian understudy at English seaside resorts, bundled in with roller skating rinks and dance halls. These became eventually déclassé, just as Victorian historicism and eclecticism did, leading to a reactive, masculine, mechanistic Modernism—but interior plants are never gone for too long.

By the advent of early Modernism, there was a real tendency to spurn nature, to be sure, but Sparke’s study again shines in excavating a Modernist return of interior planting, a strain that has been “studiously ignored.” A particularly intriguing chapter is on the Villa Tugendhat, whose potted maple atop the steps receives a close read, “strategically placed on the floor at the point where all those elements met, softening the hard geometry and surrounding materials but also, arguably, providing visual resolution to, or perhaps a distraction from, the multiple materials and the spatial complexity of the verticals, horizontals, curves, straight lines, masses, and voids that came together at that point.”

The winter garden along the eastern side of Tugendhat’s lower level also receives overdue analysis. Sparke explains that it “functioned like an enormous painting or cinema screen, bringing tamed nature into the interior, but, at the same time, restraining it and not letting it invade.” These plants are present in vintage photos of the house, and plants are in the same location now, though they hardly ever receive a word in accounts about the house. Sparke rightly asserts their consequentiality as design elements, playing obviously intentional roles in softening an austere materiality.

Sparke notes that this oversight can be partially explained by the issue of agency: We sometimes don’t know quite who placed or selected plants, which has led to their being ignored if it wasn’t clearly the architect-auteur and to the assumption that plant placement was the work of some frivolous housewife. Rather, she argues, these are clearly aesthetic interventions that deserve attention no matter who was responsible.

Sometimes, as with her chapter on California Modernism, there’s no question that plants were envisioned from the drafting table, as with the soil beds inside Lautner’s Sheats-Goldstein House or Soriano’s Case Study House in Beverly Hills. E. Stewart Williams’ Edris House features gravel beds and similar plants on both sides of glass, providing an illusion of seamlessness. Potted plants skillfully ease the transition between interior and exterior at Pierre Koenig’s Bailey House. There are other ambiguities worth pondering though; We know that Julius Shulman would move plants around to achieve a desired photo frame, but the plants were around in the first place, present as decor in some form or another and deserve attention.

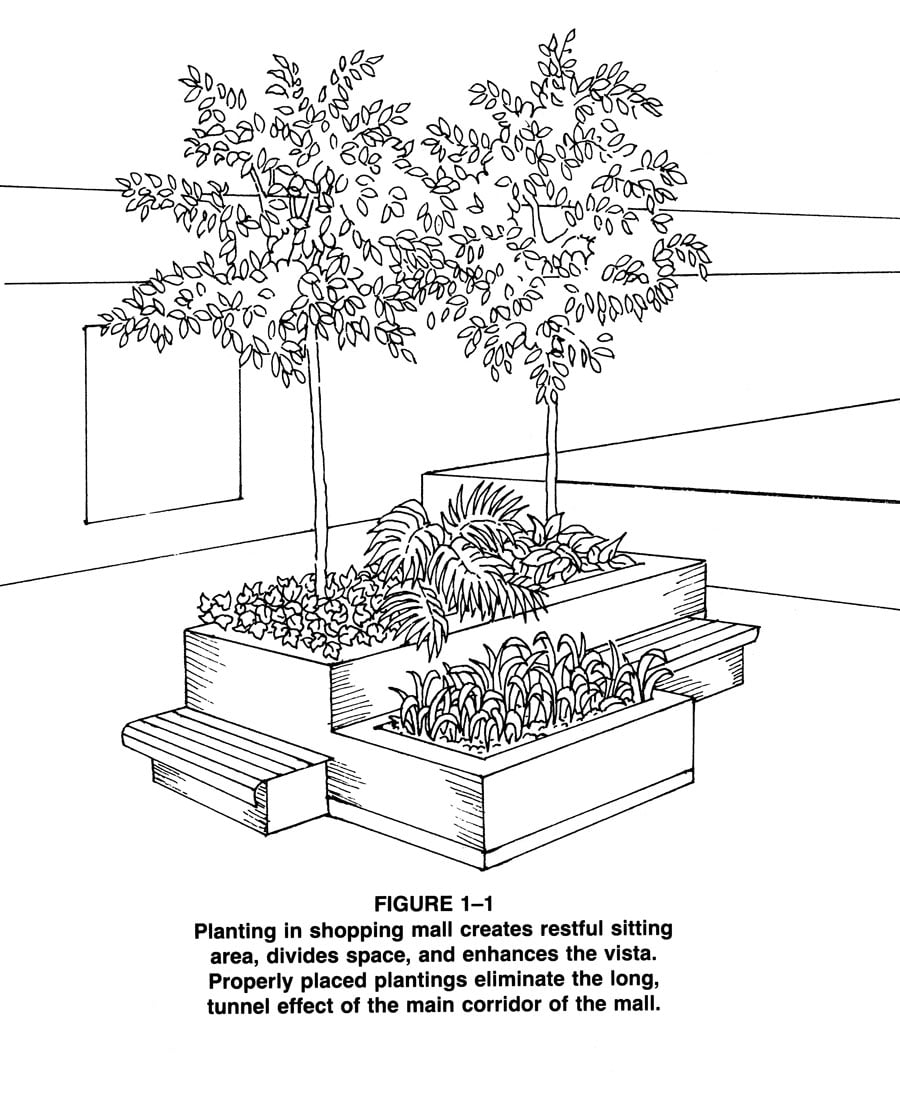

Sparke’s account of the postwar rise of interior landscaping as a business features all sorts of fascinating content, such as details on figures like Everett Conklin, whose landscaping company worked on the Four Seasons and the Ford Foundation. This was a big business: 22,000 vines and other plants were planted in the Ford Foundation, 2,400 vines in Portman’s Hyatt Regency in Atlanta. It’s not easy being green—the bill for the Hyatt initial planting was $100,000 in 1967 (something like $780,00 today).

This only escalated, with the rise of large-scale efforts to empirically evaluate the health of interior environment, some of which have delivered clear conclusions, some of which haven’t. There are new concepts such as sick building syndrome, overload and arousal theory, and a whole range of neologisms, like plantscaping, biophilia, and greenwashing. “Nature” has become integrated into much corporate practice, evinced in examinations of the role of plants in Quickborner office planning and Herman Miller’s Action Office plan.

Not everyone is a sincere naturalist, Sparke cautions: “Agendas underpinning the decisions to introduce nature into those large public interior spaces ranged from a genuine attempt to improve people’s lives to unapologetic commercial exploitation.” Whatever the subsurface motivation, it’s difficult to argue that results aren’t almost universally pleasant. It is a minor bright spot amidst much that isn’t, Sparke writes. “Nature inside’s life-affirming qualities undoubtedly act as a form of compensation for some of the less life-affirming aspects of contemporary life.”

You may also enjoy “Strelka Institute’s Three-Year Research Agenda Culminates with The New Normal”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025