October 18, 2016

New Talent: Seven Innovative Design Studios to Watch

As always, our annual New Talent list focuses on crossover innovators at all scales of architecture and design.

For this year’s New Talents, we have selected a group of emerging practitioners who transcend disciplinary boundaries—from product designers who blend technology and furniture to architects challenging the limits of physical space with virtual installations.

Norman Kelley

Chicago, New York

Courtesy Norman Kelley

It’s good to let the work of Norman Kelley settle. The firm’s style comes on slyly and with a deadpan wink, like the architectural equivalent of a Steven Wright joke.

For their 2013 exhibit Wrong Chairs, Norman Kelley took the iconic Windsor chair, recognizable to anyone who’s ever stepped inside an American dining room, and exaggerated its elements. Chair legs seemed uneven and loose. Seats appeared fused together, elongated, and malformed. The chairs looked, well, wrong, but were fully functional and structurally sound.

The visual sleight of hand employed in Wrong Chairs—less a gag than a form of rigorous play—is a constant for Norman Kelley. “Upending expectations is funny, but we don’t want someone to be put off-guard,” says principal Thomas Kelley, who’s also an assistant professor at the University of Illinois-Chicago (UIC) School of Architecture. “We’re more interested in impact and the idea of gratification. Buildings sometimes overwhelm. We want to scale up our work patiently to develop attention spans that appreciate impact.”

First mounted in 2013 at Chicago’s Volume Gallery, Wrong Chairs manipulated the features of a Windsor chair to create a series of “errors” that nonetheless leaves its functionality intact.

Courtesy Norman Kelley

Kelley is a principal partner with Carrie Norman. The two attended the University of Virginia together and continued their studies at Princeton. While Norman headed to New York, where she serves as an adjunct professor at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation and was previously a senior design associate at SHoP, Kelley settled in Chicago, putting in time at SOM and teaching at UIC. The two launched their namesake firm in 2012.

Despite being based in cities hundreds of miles apart, Norman and Kelley easily bridge the geographic divide. As Kelley says, “We’re in constant conversation,” adding that they collaborate at every step of a project, be it academic essays for journals such as The Avery Review, theoretical tracts (see EYECON, a book released as part of architect Jimenez Lai’s Treatise series), or a residential rehab.

“There’s no distinction for us between academic and professional practice,” Norman says. “When it’s client-driven, we have to relinquish some control. The work is then helping to edit the idea, maintain a kernel of what we’re after within a body of work. For us, clients are our collaborators.”

Earlier this year, the designers completed their first retail project for the skin-care brand Aesop.

The small shop, in Chicago’s Bucktown neighborhood, employs intricately patterned brick in an interior; the brick casts an almost pinkish hue and forms a pleasing yet earthy backdrop for products.

Courtesy Aesop

When Aesop, the Australian skin-care company, commissioned Norman Kelley for the build-out of its first Chicago store, it was intrigued in part by the duo’s conceptual and collaborative approach. “Carrie and Thomas seemed genuinely inspired by our design constraints, and the challenge of expressing their voice within them,” Aesop creative director Marsha Meredith says. The small shop in the Bucktown neighborhood uses reclaimed Chicago common brick to create an engaging, attractive space for merchandise. Of course, the use of the ubiquitous material riffs on the materiality and composition of Chicago itself. The end result is particular to its place, while also reinforcing Aesop’s commitment to local design. “We design our stores to add something of value to a neighborhood, rather than be a discordant presence,” Meredith says.

The Bucktown store led to a second Aesop commission, in New York’s Tribeca district. “[The design] harks back to when Tribeca was an artists’ neighborhood,” Norman says, and the material used to define the space reflects that. It’s simply paint, used in an ombré fashion where black blends into white to “bring back the grit and character of the neighborhood,” adds Kelley.

The twosome are now close to finishing their first residential project, the Lewis Vinz Residence, in Chicago’s Humboldt Park. In explaining why he chose Norman Kelley to redesign and expand the footprint of his 1,500-square-foot brick cottage, homeowner Sam Vinz (whose design gallery, Volume Gallery, initially showed the Wrong Chairs exhibit) encapsulates the larger appeal of the rm. “They have this ability to turn things on their head, take existing concepts and make them new, and it’s all very accessible.” —Ben Schulman

“We enjoy working with established architects as well as rising talents. We were drawn to Carrie and Thomas’s conceptual approach: their ability to reflect on the culture and history of a place, and to draw inspiration from the arts. We knew Aesop Bucktown would be their rst retail project and were intrigued to see the mark they would leave on an Aesop store.” —Marsha Meredith, creative director for Aesop

Thomas Kelley and Carrie Norman formed their bi-city practice in 2012, several years after first meeting at the University of Virginia.

Courtesy Volume Gallery

Branch Creative

San Francisco

Technology start-up Plume calls its self-optimizing Wi-Fi provider a “router killer.” Branch collaborated with the company’s internal team to design the hexagonal jewellike pods that plug into any outlet to provide wireless internet connectivity at speeds modulated to the needs of individual devices.

Courtesy Branch Creative

Designers Nick Cronan and Josh Morenstein, who head up the San Francisco–based firm Branch, are honing a superpower: how to make technology invisible, or at least make it fade discreetly into the background. One of their latest sleights of hand is a product called Plume, which replaces the clunky, blinking Wi-Fi router in your living room with a set of night-light-size hexagons that plug into the power outlets throughout the house and create a faster, more reliable network of signals. They’re plastic, but disguised to look like hardware, with a metallic finish and colors. “Technology doesn’t always have to look like technology,” says Cronan.

While their firm is not yet four years old, he and Morenstein have the benefit of their extensive collective experience at the forefront of the city’s industrial design scene. The 47-year-old Morenstein was a partner with Yves Béhar in the firm fuseproject and its creative director for seven years, overseeing products for Nivea, Samsung, GE, and Prada. Cronan, 11 years younger, launched The North Face’s footwear line before joining fuseproject in 2005. After working there for seven years, during which he connected with Morenstein, Cronan went to another firm, Ammunition, to lead the team that produced the second generation of Beats by Dr. Dre headphones. In 2013, they joined forces to form their own company.

The biggest client that the 15-person firm landed was Google, and the project was no less than the internet giant’s first phone (a plan that the company has recently announced it will no longer pursue). The Google Ara was modularized to allow the phone to bristle, Transformers-like, with new functions. It had six slots for swapping in new modules, such as an upgraded camera or more powerful speakers. “There was a lot of complexity, since each module was a separate product,” Cronan says.

“It’s not just a phone that we had to perfect, it was 60 different products.” The kinds of futuristic devices that Branch is developing are ones that explore new forms of human-technology interfaces. “When we started the business, there was a big push for wearable tech: ‘Technology! The body! How do they relate?’” Cronan says. “What you’ve been seeing recently is a lot of people working toward making it seamless, intuitive, and functional—not focusing on what you’re wearing.” Branch has ushered a couple of next-wave products to market, including Athos, a line of exercise clothing that provides real-time feedback about muscle activity.

At the first meeting, the Athos folks showed a prototype suit that included a communications module that literally plugged into the suit. “You’ve got wires and electronics next to your skin, and then you plugged [the module] in—it felt too mechanical,” Cronan says. The Branch team helped refine the garments, embedded with thin stretchy wires, then transformed the rectangular module into a smooth pebble that slips gracefully into a little pocket. “The big ‘aha’ moment for us was getting rid of the USB port,” says Morenstein. Instead, the pebble has a grid of 42 raised dots, 38 of them made of conductive rubber, which are responsible for the information transfer. “Something that we like to do on all our projects is question both the functional and aesthetic paradigms,” he says.

Branch’s Drift Collection for Council debuted at ICFF in New York during NYCxDESIGN this past May. For the debut, Branch also created a limited-edition version with a brass plate made in the Cirecast foundry.

Courtesy Branch Creative

For designers who spend so much time working on the next big gadget, it’s surprising to learn how passionate the two are about furniture design. For them, such side projects are important exercises in creating products with longevity. “A cell phone might last two years or six months, and we try and stretch that time out,” Cronan says. “But on the other end we do furniture that we design to last a hundred years or more, which is a totally different perspective and approach—and there’s unique crossover and inspiration that comes from one extreme to the other.”

Their furniture, perhaps even more than their technology practice, exemplifies their take on product design: deliberately understated, with subtle twists. At this year’s ICFF, San Francisco furniture manufacturer Council debuted its latest collection, called Drift. Rendered in solid ash, the bar stool, side table, and coffee table have classically simple forms. But the tabletops look as if they’re balancing on top of the legs, held together just by friction, and the footrest of the bar stool similarly appears to just graze the legs. Of course, carefully concealed bolts are responsible for the illusion. “Something that we’ve really learned from the furniture world is the notion of sophistication,” Cronan says. “It’s not so much about features, but about details that you fall in love with.” The bar stool’s triangular seat invites leaning, so you can pause and then “drift” on by in a casual workplace or domestic setting. “Every project has a different balance that you need to strike,” Morenstein says, “between being new and being familiar.” —Lydia Lee

“Josh and Nick are longtime members of the Bay Area design community, and I’ve known them personally for many years. My first direct experience with their work came not through furniture, but because they designed the phone that I carry and use (Nextbit Robin). I suppose one thing that distinguishes California design in general, and Branch’s work in particular, is the ability to take a human sensibility to devices. That’s what we want—we certainly don’t want to bring a technical sensibility to our furniture. Branch has this human sensibility, and whether it’s the Drift collection they’ve designed for us, or the phone in my pocket, you get the same thing.” —Derek Chen, founder, Council Design

The founders of Branch, Josh Morenstein (pictured left) and Nick Cronan, both come from family backgrounds steeped in design. Cronan’s parents cofounded a namesake graphic design studio, creating identities and design strategy. Morenstein grew up working summer jobs at his father’s metal foundry, Cirecast, and Branch operates an internal fabrication shop there to this day.

Courtesy Molly Matalon

Sibling

Melbourne

SIBLING’s installation—a gesture to physically connect people in a space using architecture to create a filter between the individual and the world—was part of the ON/OFF exhibition at the University of Melbourne.

Courtesy Tobias Titz

For young Melbourne-based firm SIBLING, being an emerging practice provides opportunities for serious experimentation. In the four years since formally establishing SIBLING, its five directors—Amelia Borg, Nicholas Braun, Jane Caught, Qianyi Lim, and Timothy Moore—have worked on a wide range of exhibitions, solid commercial and retail fit-outs, and residential projects.

“We’re lucky because we’ve had a lot of small projects in which we’ve been able to experiment with our conceptual ideas,” explains Lim, sitting within their very white, very welcoming fourth-floor inner-city studio. “These projects move quite quickly, and you see the outcomes of your design in a shorter period of time.”

Each one is informed by those that came before, forming part of an ongoing research and participatory approach that sets SIBLING apart. Rather than waiting for work to come to them, the young practitioners also research and develop projects of their own. “It’s about the architect or the designer moving beyond just receiving a brief and implementing it, but perhaps searching out issues within a community or space and proposing a project where there’s no client, per se, involved,” says Lim.

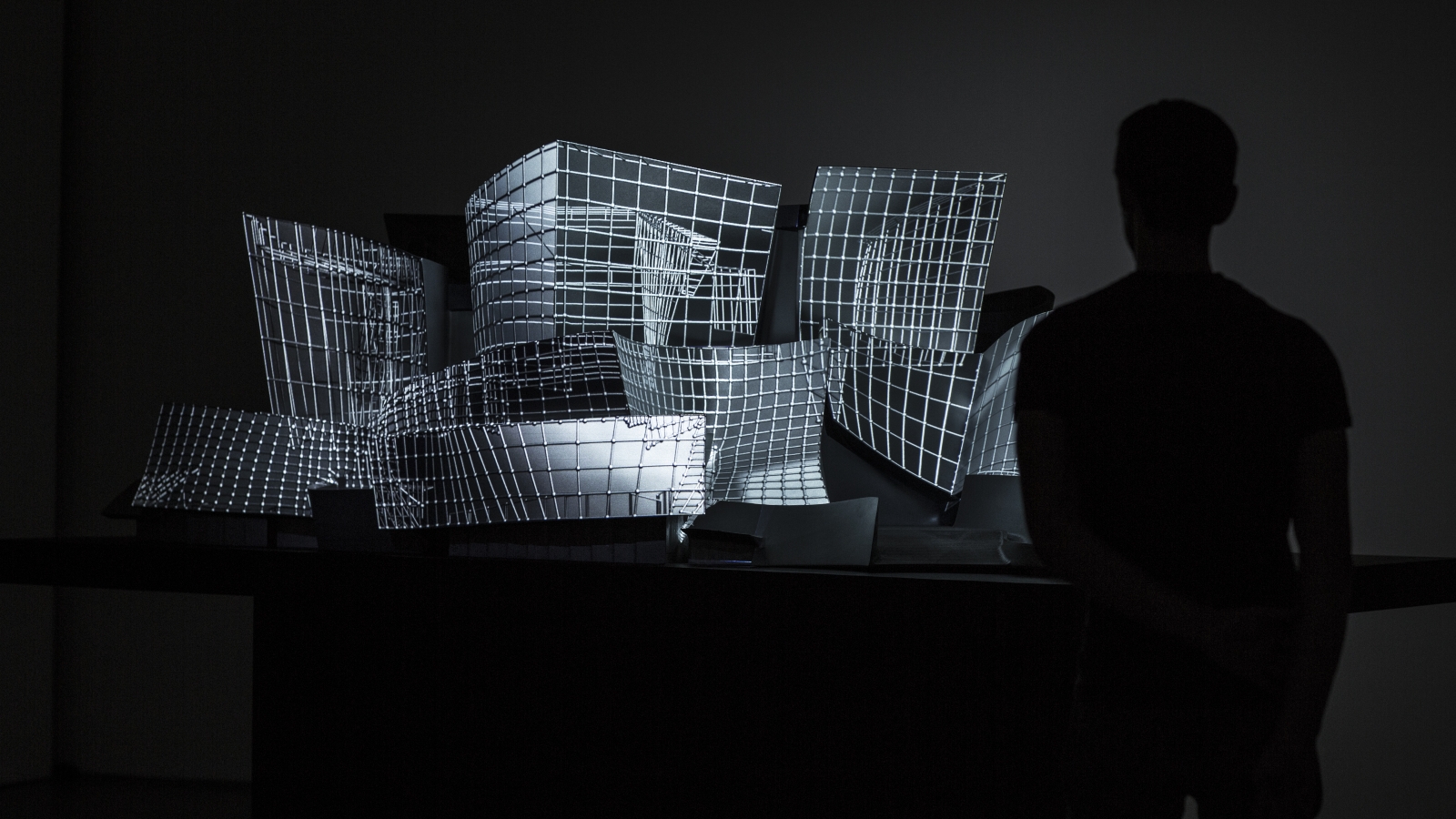

The Australian headquarters of visualization and animation studio Squint/Opera. SIBLING’s design uses the wireframe space of modeling software as real-time infrastructure through the installation of custom-steel grid-mesh.

Courtesy Christine Francis

One example is the ON/OFF exhibition at the University of Melbourne, which explored the intersection of the digital and physical worlds. ON/OFF played with the idea of a modern-day “Faraday cage” by creating “a starkly warm space” where smartphone reception was blocked. These conceptual investigations have implications for SIBLING’s more commercial work. “The question was ‘What happens when the digital and the physical fold into each other?’” says Lim. “The answers to this then found their way into our retail fit-outs, one of which, DUST, looked at bringing a digital commercial platform into a physical retail space.”

As SIBLING takes the leap into larger-scale work, those early experimental projects continue to inform its approach. Unencumbered by the weight of an established practice, SIBLING has the freedom to design a business unique to its founders’ process, their clients, and their community. The result is a practice far greater than the sum of its parts. —Ben Morgan

The five directors of SIBLING are Timothy Moore, Amelia Borg, Qianyi Lim, Jane Caught, and Nicholas Braun.

Courtesy Tin & Ed

“The way that SIBLING works as a collective is very telling of the future of design practice—the group is conceptual, responsive, dexterous, and highly engaged. I think the near future will prove their ability as adaptive creative practitioners. This will manifest in the quality of their diverse and rigorous design work but, also as importantly, in their ability to connect with and inspire communities with progressive design ideas.” —Fleur Watson, curator at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology’s Design Hub

Refik Anadol

Los Angeles

When media artist Refik Anadol arrived at Los Angeles International Airport in 2012, the first thing he did was rent a car and drive to Walt Disney Concert Hall. Jet-lagged after his long flight from Istanbul, where he was born and was immersed from an early age in computing, cinema, and photography, he stood outside in awe. “I was dreaming of what would happen if this building was embedded with memories, intelligence, and culture,” says Anadol.

Like Hollywood’s TCL (formerly Grauman’s) Chinese Theatre, which once drew would-be starlets who imagined their handprints in the concrete, Frank Gehry’s icon enticed him with the hope of realizing a dream. Fame wasn’t part of the equation, exactly, just a desire to create a large-scale video artwork across the swooping facade.

After studying in Istanbul and creating digital and interactive artworks throughout Europe, Anadol moved to Los Angeles to pursue an MFA at UCLA’s Design Media Arts program. The Disney Hall project was part of his studies and led ultimately to a presentation at Microsoft Research’s 2013 Design Expo. As he spoke about the idea of architecture as a canvas and light as material in his eight-minute elevator pitch, Anadol caught the attention of Dennis Sheldon, chief technology officer of Gehry Technologies. Before Anadol knew it, Gehry Technologies offered the use of the original 3D model so he could create a full-fledged case study called “Ethereal.”

Images Courtesy Refik Anadol

“They said, ‘Frank loved your idea, we’re giving you all the files,’” he recalls with the enthusiasm of someone who still can’t believe his good luck. The Los Angeles Philharmonic (LA Phil) later commissioned Anadol to create an immersive experience inside the concert hall that would be responsive to the architecture, music, and movement. With data from the Gehry model and a team of UCLA researchers, he created the 2014 Visions of America: Amériques. Inspired by Poème électronique, a 1958 collaboration between Le Corbusier, architect/composer Iannis Xenakis, and composer Edgard Varèse, he used real-time custom software to project images across the architecture, which changed and morphed according to the music and conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen’s movements (tracked by a Microsoft Kinect motion-sensing camera).

The collaboration with LA Phil continues in 2017 with Phenomena, a research project and performance by Anadol, the orchestra, and academics and scientists at UCLA and UCSF, underwritten in part by Microsoft Research. The concept will use Enobio neuroelectric sensors to collect brain-wave information from participants as they listen to music. Emotions like joy or wonder will change the visual environment of the concert hall—and the experience of the audience.

“We have complete control of poetry— the image, the sound,” explains Anadol. “You’re inside a complete idea that is way beyond the screen.”

Architecture, of course, lives in the brick-and-mortar or steel-and-glass world of gravity and materiality, and is resistant to transcending itself. One has only to look to Times Square or Shenzhen’s skyline to find the limitations of LED screens and digital facades. Yet Anadol is confident that the post-digital is possible. In 2015, he installed his first public-art commission for 350 Mission in San Francisco. In collaboration with high-rise architects SOM and Kilroy Realty Corporation, he placed the artwork Virtual Depictions: San Francisco in the building lobby. A 20- by 40-foot LED display wraps around two walls. On-screen, a 90-minute generative animation, including a 3D model of San Francisco, responds algorithmically to location data collected from Twitter. “The city itself is so intelligent already,” he muses. “What would happen when public art meets public data?”

Virtual Depictions: San Francisco / Public Art Project from Refik Anadol on Vimeo.

He’ll find out when another permanent public-art piece opens next year. It will give him another chance to experiment with how to loosen architecture’s grip on reality. Developed in collaboration with Susan Narduli Studio for the mega-development Metropolis in downtown Los Angeles, the untitled artwork will be his largest to date.

Custom software will animate a 100-foot-long low-resolution screen that will be visible from the 110 Freeway. Anadol considers it site-specific sculpture, a foray into what he calls a “post-digital architectural future.” “Post-digital is what comes after the full digital immersion in everyday life caused by our devices, social media, and sensors,” he says. “Media architecture is bigger than cinematography or VR—people are so interested in virtual reality or augmented reality, but we haven’t fully explored the nature of reality.” —Mimi Zeiger

“Refik has an incredible lens through which he views and interprets data in the world. He has an uncanny ability to sift through complex data, create the digital tools and software to process it, and the creative vision to transform it into a beautifully immersive experience. His process allows for a high level of collaboration and communication with others that utilize digital tool sets. As a digitally driven manufacturer, we love this type of exchange as it strengthens the project throughout the entire process, yielding amazing results.” —Sebastian Munoz, director of project design and development, Arktura

Tropical Space

Ho Chi Minh City

Completed in 2016, Tropical Space’s Terra Cotta Studio provides the workspace for artist Le Duc Ha. Bamboo-frame scaffolding acts as a drying rack for the terra-cotta works, while the exterior is made from solid clay brick, resembling a furnace.

Courtesy Oki Hiroyuki

Tropical Space might not yet be a household name, but that looks set to change with the Ho Chi Minh City–based studio’s considered, ecofriendly approach to architecture that brings an elevated, avant-garde quality to the simplest of building materials.

The founders, Nguyen Hai Long and Tran Thi Ngu Ngon (a couple in business as well as life), met while studying at Ho Chi Minh City University of Architecture and say their “break” came when they decided to focus on solving the challenge of living in a tropical climate. “Housing design in modern Vietnam is quite closed with rooms having thick walls and doors for air-conditioning. We create more porous designs to allow the house itself to breathe.”

The lower floor has a turning table on which the artist can create works.

Courtesy Oki Hiroyuki

The studio has a growing portfolio of local projects including an artist’s studio and a spa. Their two-story Termitary House in Da Nang offers the perfect example of the duo’s functional conceptual style: An innovative facade composed of traditional red baked bricks arranged in an intriguing double lattice-like skin gives the residence a strong graphic quality while delivering fresh breezes and an ever-shifting pattern of sunlight.

Inside, the layout is kept simple yet spatially efficient with a large open-plan living area decorated with custom-designed furniture made from timber recycled from the roof of the old house. “We look to give people more chances to see and talk to each other in our designs,” Nguyen explains. “With furniture, we design it to be consistent with the architecture, but more importantly, we provide a very simple design to save costs.” —Catherine Shaw

“Tropical Space are clearly pioneers in that they’re not just filling a need, but are actually creating new opportunities for contemporary architecture in a place where those opportunities have been scarce. And they’re doing so by pragmatically using rudimentary materials and construction techniques to produce extraordinary results. They’re not only opening our eyes to what’s possible in Vietnam, but perhaps more importantly, they’re showing the Vietnamese what’s possible at home.” —Aric Chen, M+ lead curator of design and architecture

The founders of Tropical Space, Tran Thi Ngu Ngon and Nguyen Hai Long. The firm combines its inherent understanding of Vietnamese climate and culture with its passion for sustainable materials and building practices.

Courtesy Tropical Space

APRDELESP

Mexico City

The young design outfit APRDELESP does a little of everything, operating a print shop, art gallery, design office, and even a furniture showroom (above).

All images courtesy APRDELESP

Of the 30 or so employees of ELHC, the research arm of the Mexico City architecture office APRDELESP, not a single one is a designer. Instead, they are managers, dishwashers, cooks, and servers, supporting a panoply of commercial ventures, or “subspaces”: a restaurant (Café Wi-Fi Café Zena); a café that doubles as a showroom for a made-to-order metal furniture line (Muebles Sullivan); a window display–size art gallery (Galería La Esperanza); a print shop (Macolen); and, until earlier this year, a pair of convenience stores (Comidas, Bebidas, Revistas). For APRDELESP’s Rodrigo Escandón and Guillermo González, architects preoccupied with how space gets used and wary of design that smothers the everyday, the disciplinary imbalance is practically an accomplishment. As Manuel Bueno, a frequent collaborator and ELHC partner who runs his own graphic design studio, jokes, “Instead of buying nice Herman Miller chairs, we just open a space.”

Skeptical of the tired orthodoxies of professional design practice from the start, APRDELESP has been working to circumvent them ever since its first project, a restaurant, in 2011. “It went really bad,” recalls Escandón of the vexed commission. “We were working in a traditional way, trying to defend our ideas and also trying to sell our ideas.” A few months later, already plotting ways to escape this transactional dynamic, the designers were offered the lease on a ground-floor space in the San Miguel Chapultepec neighborhood.

Looking to provide a revenue stream and ensure the 430 square feet remained in a constant social flux, they settled on the idea for Café Wi-Fi Café Zena. They designed the tables and chairs and walls and graphics. And they conceived the collective ownership structure—a joint-venture model with low buy-ins and transferable shares that has been replicated in other subspaces since. Plenty of architects have acted as their own clients to pad out their portfolios, but Escandón and González were interested in what the space could do, and in producing better conditions for their work. “More than a project to show off,” Escandón explains, “we wanted an experimental project, to think.”

In fact, the architects achieved both. As new ELHC subspaces opened, commissions followed (primarily apartment and office renovations), and the entrepreneurialism and experimentation became harder to disentangle from their design work. APRDELESP’s highest-profile (if small-scale) projects involve exploiting ELHC’s resources. When Museo Jumex commissioned fixtures for its new David Chipperfield–designed building in 2014, APRDELESP produced wastebaskets and pamphlet stands from Muebles Sullivan’s furniture system. And last year, when asked by Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura to participate in an exhibition, APRDELESP had a tiny coffee kiosk built along the perimeter of the institution’s walled garden. On one side, the kiosk, which was operated by ELHC, served gallery visitors; on the other side, through a place mat–size opening in the wall, it served pedestrians traversing a barren stretch of sidewalk that abuts a bleak thoroughfare—an infrastructural space that architecture could never compete with but a functioning concession stand proved able to enchant.

Asked to participate in an exhibition at Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura, Mexico City’s premier design gallery, APRDELESP responded with an intriguing proposal. The complex’s lush garden is bounded by a large wall, which screens off a major causeway and a depressing pedestrian path.

The designers carved out a hole in the wall to create a café window for passersby.

Most afternoons, Escandón, González, and Ricardo Matias (a collaborator since 2013) can be found working in one of the subspaces. These are where they met all four of their current clients. “Maybe if you’re private you have to sell yourself,” says González, his hesitation proof of the statement’s veracity. This approach to public relations not only bypasses publicists but, Escandón adds, “puts the emphasis on the dynamic rather than a formal style.”

In resisting a formal signature, APRDELESP has honed a representational style that embodies its design methodology. A project, or case study, as it is referred to, does not culminate with a thoroughly curated set of photographs but lives on as an overabundance of casual snapshots documenting initial surveys to construction to full-fledged inhabitation. (APRDELESP, an abbreviation of apropiación del espacio, is a mantra as much as a name.) Similarly, drawings, color-coded in red, blue, and black, delineate preexisting spaces and recommended changes, as well as catalogue the sorts of belongings most architects would rather pretend do not exist, like kitchen appliances and kitschy knickknacks.

This interest in everyday life and its unprejudiced documentation calls to mind Wajiro Kon, the Japanese architect/ ethnographer who around the middle of the past century critiqued the high Modernist prohibition on “traditional” habits by exhaustively sketching people’s personal possessions in their domestic settings. But are the customs and artifacts of APRDELESP’s clientele—the capital city’s cultural elite—really so ordinary? In this sense, these designers represent business as usual in their field. Which is why their interrogation of business and of the practice of design is so vital. —David Huber

APRDELESP founders and collaborators include Rodrigo Escandón, Guillermo González, Ricardo Matias, and Manuel Bueno.

“APRDELESP are the enfants terribles of Mexico City’s architecture scene, which desperately needs a good shake down, stuffy and set in its ways as it is. They are terribly serious about not taking themselves too seriously. For me they’re one of not even a handful of local offices that are truly experimenting with architecture, pushing the practice beyond (or sometimes below) its expected scope and scale.” —Mario Ballesteros, director of Archivo Diseño y Arquitectura

LCLA

Medellín, Oslo

Luis Callejas is a 35-year-old Colombian architect and founder of LCLA. Callejas and frequent collaborator Charlotte Hansson, a Swedish architect and fashion designer, recently proposed an extension for Oslo’s Viking Museum, whose folksy 1928 building can no longer accommodate the institution’s collection.

Courtesy Luis Callejas & Charlotte Hansson/Mantheykula and Groma

Today, terms such as ecology and interdisciplinary have become self-serving signifiers for the many architectural firms that use them. But LCLA, a small design studio run by the Colombian architect Luis Callejas with bases in Oslo and Medellín, is built on the conviction that architecture can encompass landscape, cartography, and even botany.

Educated at the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Callejas belongs to a generation of young Colombian architects who came up with the design-conscious public amenity programs of Bogotá and Medellín of the past decade. (The Parque Biblioteca España, Medellín’s iconic public library perched on a hilltop, is just one of the fruits born from these initiatives.) During this time, Callejas’s designs rose to prominence through his participation in a series of open public competitions, when he was a founding member of the now-disbanded office Paisajes Emergentes.

One such competition resulted in his first and most prominent built work, the Aquatic Center in Medellín for the 2010 South American Games. The split-level complex embedded swimming pools in a vast concrete “field” that concealed the architecture proper underneath. Exposed to the air, the pools themselves were delineated with wetland plantings to create the impression of a series of islands, transforming the typically restricted sports-arena typology into an open public park and a citywide amenity.

Callejas’s breakout project, the Aquatic Center in Medellín for the 2010 South American Games, featured a cluster of swimming pools open to the elements (Medellín enjoys springlike weather for most of the year) as well as to the public. It quickly became a torchbearer for public-space advocacy in the city.

Courtesy Iwan Baan/Luis Callejas

The “island,” both metaphorically and morphologically, has become a central conceptual motif for Callejas. (He produced a book on the topic for the Pamphlet Architecture series in 2013.) “Naturalists have always been interested in islands because that is where evolution happens faster or slower,” he muses. “With containment, strange things can happen.” This microcosmic notion also speaks to his own position as an architect operating within landscape.

In 2011, Callejas, then just 29, accepted a lecturer position at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (GSD), where he subsequently established LCLA. The milieu of the GSD, then alive to competing theories of landscape and ecological urbanism, provided him with both a platform and a foil for his ideas and work. While acknowledging the relevance of ecology, Callejas eschews the performance-driven parametricism of contemporary landscape discourse. As he explains, “I’m interested in basic, simple geometry and engaging with ecosystems simply by contrast.”

Callejas shuns rigid architectural promenades or prescriptive landscape sequences and instead aspires to cultivate atmospheres. To that end, he admits, “representation has been an extremely important part of my practice. It started as a way to bridge the limitations of architecture to engage with landscape as a medium.” An unexpected collision of photography, painting, and drawing is manifest in his beautiful collages, which are the most identifiable (and emulated) aspect of his work.

Through these evocative drawings, LCLA’s projects employ a language of repetition and blunt form to effect change on territorial scales. In “The River That Is Not,” a study for the contaminated and canalized Medellín River, LCLA mounted a decentralized strategy that purported to marry hydrologic remediation with public engagement. Rather than renaturalize the river, as boosters advised the city to do, Callejas proposed treating local streams while reclaiming the concrete canal as an urban amenity, with simple pavilions for a public library, kindergartens, and recreation areas. In addition to creating adjacencies between public infrastructure and public space, his work has implicit political resonance. His contribution to this year’s Oslo Architecture Triennale explores spatial politics through questions of territorial waters and maritime law.

Callejas’s recent appointment as associate professor at the Oslo School of Architecture and Design will see him navigating new waters. With his frequent collaborator Charlotte Hansson, he is beginning to analyze topographical sites in the Andes and the Norwegian mountains in a project that plays off the unlikely binary of Nordic versus tropic. And in an inversion of the typical career trajectory, he is also working on smaller residential jobs in Colombia years after he got his start designing ambitious public buildings and later sketching out plans for whole swaths of regions. “It is very interesting how working with large projects can influence how you work with small scales,” he says excitedly. “That’s an experiment.” —Khyati Saraf

For the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial, Callejas worked with Hansson to produce 21-foot-tall silk curtains, which were hung in the Cultural Center. They featured illustrations and hand-drawn sketches depicting LCLA’s designs, irrespective of sketch or program.

Courtesy Luis Callejas & Charlotte Hansson

“I was happy to be able to recruit Luis from his native Colombia in 2010, shortly after I arrived as chair at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). I believe he is among the most talented young urbanists practicing today, and his work has been central to the discourse around landscape urbanism and ecological urbanism.” —Charles Waldheim, John E. Irving Professor of Landscape Architecture, GSD

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025