May 11, 2018

The Designers Who Made Disco

The nightclub has always been a fiercely creative and radical architectural typology, a new exhibition at the Vitra Design Museum argues.

What can’t be done on the dance floor? Not much, said the 1960s Radical Design collective Gruppo 9999, which argued that discos should be “a home for everything, from rock music, to theater, to visual arts.” Other artists and designers— including New York bad-boy painter Jean- Michel Basquiat, architect Peter Cook of Archigram, and Manchester’s “cathedral of rave” creator Ben Kelly—saw the dance floor as a more subversive setting: one where boundaries could be blurred and thresholds crossed, where partying and politics could be woven together in the dark to channel a cultural revolution. Night Fever at the Vitra Design Museum stitches together this conception of the nightclub as a social Gesamtkunstwerk.

Though organized as four exhibition halls corresponding to a loose chronological narrative over five decades, Night Fever eschews strict timelines to focus on broader thematic angles that allow the various phases and trends of club culture to crossfade in the dark. Fashion, pop and subcultures, social progress, and rampant commercialization bob in and out throughout the show. Night Fever first teleports visitors into the ecstatic and hypnotic world of 1960s Italian Radical Design through a futuristic glowing corridor. A fluorescent red arrow electrifies a smooth aluminum enclave that expands into a cavernous dark room in which neon signs, pulsing music, designer furniture, and club paraphernalia converge under- neath the gleam of glass vitrines.

The premise of this first room, named “Beginning to See the Light” in a nod to rock ’n’ roll deities the Velvet Underground, is simple: Pop and rock music revved up an emerging youth culture across Europe and the U.S., which claimed the nightclub as a social factory. “The ’60s was the first—and, really, the only—time that nightclubs served as a space for young people to meet and share ideas,” cocurator Jochen Eisenbrand suggests while standing in front of a modular scaffolding unit that emerges from a corner of the gallery. (Eisenbrand organized the show with Catharine Rossi and Nina Serulus.) The gleaming metallic growth—known as a space frame system, it was invented by German engineering company MERO in the 1940s— creates an optical illusion against a floor-to-ceiling backdrop of a night spent at iconic Italian club L’Altro Mondo.

While it kicks off in Italy, Night Fever quickly extends its gaze across cities and continents to examine how architects and designers from New York to Paris answered the call of the night. Reading the nightclub as a new building typology, the first room surveys the rise of modular interiors and custom-designed furniture that responded to the hallucinatory environments conjured by high-tech lighting machinery. Beneath the geodesic- like space frame installation sits a candy- colored example of Cesare Casati and Emanuele Ponzio’s translucent and illuminated furniture, designed in Bolzano, Italy, in 1968. It cozies up to the all bark, no bite of Roger Tallon’s Swivel Chair Module 400 No° 3 (1965), whose ominous spikes are in fact made from plush anechoic-chamber foam.

With such a supersensory subject in hand, Night Fever doesn’t skimp on entertainment. For audiophiles (or those big on flashing lights), the clear highlight of the exhibition is Konstantin Grcic and Matthias Singer’s interactive installation that consumes Hall 2. Like entering a giant disco ball, ducking under the dropdown walls and moving up onto the dance floor bring visitors into their own private nightclub. Headphones dangling from the light-up mirror-plated ceiling tell a sonorous story of four eras of music— pre-disco, disco, house, and techno— expertly compiled by the musician and exhibition consultant Steffen Irlinger. The goal here is to bring visitors into intimate contact with the contagious energy of the music while also unraveling its stylistic evolution through the decades. It’s obviously a huge hit: I watched multiple visitors let loose on the light-up dance floor, including a rather demure septuagenarian with an apparent penchant for deep house music. (Fear not, wall flowers: Dancing is optional.)

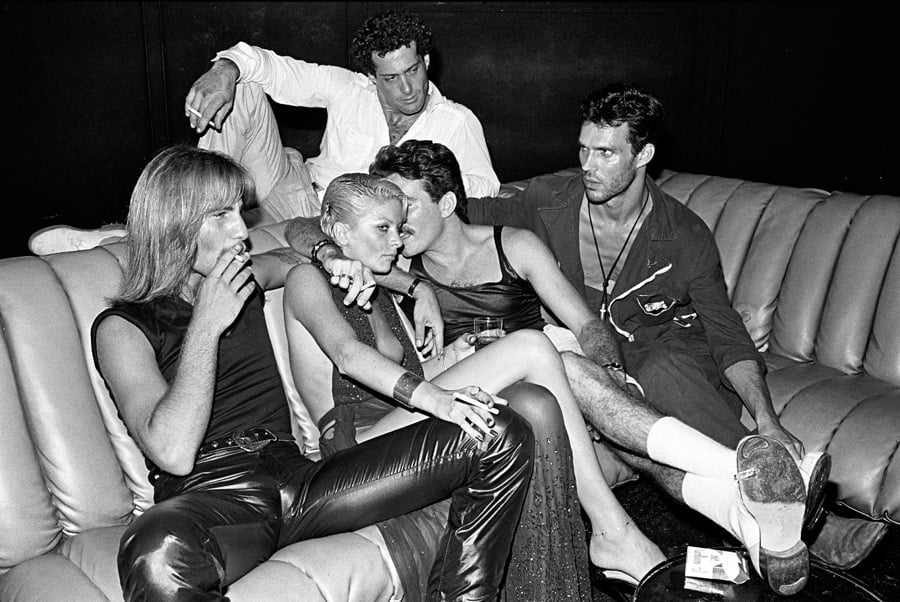

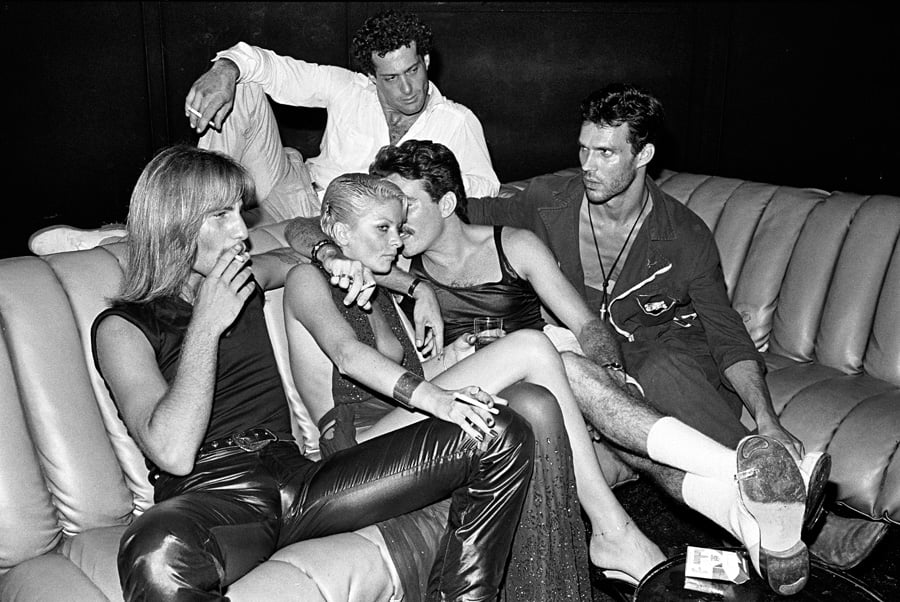

The party sobers up somewhat in the third room, themed “Slave to the Rhythm,” homing in on disco’s hypercommercialization. A cringe-worthy clip from the 1977 film Saturday Night Fever illustrates how disco went straight from queer subcultural sanctuary to sleek Hollywood backdrop. In a cruel death for the radical ’60s daydream, the ecstatic underground discotheque grew streamlined in a push for capitalist gain. But Night Fever doesn’t get bogged down in the obituary, instead forging onward with the swift uptick of house music, which vibrant club scenes all cropped up in moments of political upheaval, from postwall Berlin to Detroit’s economic distress, and the gentrification of New York in the ’80s and ’90s,” explains Eisenbrand. In a sense, club culture in the ’90s became a way of reckoning with the fractured memory politics of shrinking cities; moreover, it was a chance for those inhabiting such transitional spaces to redefine their—and the city’s—culture. Of course, the anonymous architecture of these nightclubs made them a brand in and of themselves—with Berlin’s Tresor (est. 1991) and Berghain (est. 2004) doing their bit in promoting techno as part of a viable tourist economy.

The link between hypercommercialization, brand allegiance, image consciousness, and nightclub culture carries Night Fever into the postglobalized present, where the fourth and nal hall (“Around the World”) addresses clubbing in the 21st century as a worldwide phenomenon. The DJ has been canonized as a cult figure— often wielding his or her own fashion line, or sponsored by trend-savvy brands—just as the nightclub functions as an economic node in competitive global cities, including Amsterdam, London, and New York, that have appointed their own “night mayors” to promote urban nightlife.

More fascinating still, Night Fever points out the paradox of digital media’s influence on the vitality of club culture. From Boiler Room YouTube DJ sets to online music festivals, social networks offer an alternative space to congregate that is quick and easy to access, and free of charge. Meanwhile, IRL venues already up against ever-climbing rents are being forced to innovate—a new pressure that, Night Fever astutely observes, has revived interest in the precise visions of futuristic architecture and design of ’60s club culture, including the mixed- use daydream of theater producer Joan Littlewood and architect Cedric Price’s Fun Palace (1964). Pop-up and hybrid venues have combined with a renewed focus on migrant music and arts festivals emphasizing the creation of place amid non-place, such as the desert parties of Burning Man and Coachella. Work by contemporary archistars like OMA and the Turner Prize–winning artists and architects’ collective Assemble features alongside the equally brand-label-focused cultural capital of Miu Miu, Prada, and Gucci, whose recent collections have adopted the aesthetics of club culture.

From politics to design, a countercultural fervor mirroring the social revolution of the ’60s and ’70s is sweeping across the contemporary scene. In architecture and design, the pop-loving and transparent movements of Pomo and high tech are resurrected and deified; from the schizophrenic pattern clashing of Gucci to the ubiquity of rose gold iPhones, material culture’s glitz and gaudy extravagance are back in business. Club culture has always inhabited this sticky in-between space: As likely to crop up on the catwalk or in furniture trade fairs as the grungy underbelly of Berlin’s techno scene, equally at home in celebrity-DJ YouTube channels and in government-sponsored regenerative architecture contests, the nightclub has always influenced haute couture and pop culture in equal measure. Perpetually teetering on the edge of extinction, it is a fiercely resilient and radical typology. Night Fever begs us to stay out a little later, to soak up these excesses and nonsense of the night a little longer—because who knows what the world will look like the morning after.

Night Fever is on view at the Vitra Design Museum through September 9, 2018.

You might also like, “For the Design of the Met’s Costume Institute Show, Diller Scofidio + Renfro Channel the Sublime—and Mies.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025