July 20, 2017

From Overt to Covert: How Segregation Persists in America

Housing discrimination has not been eradicated. Its methods are simply more subtle, and sophisticated, than ever before.

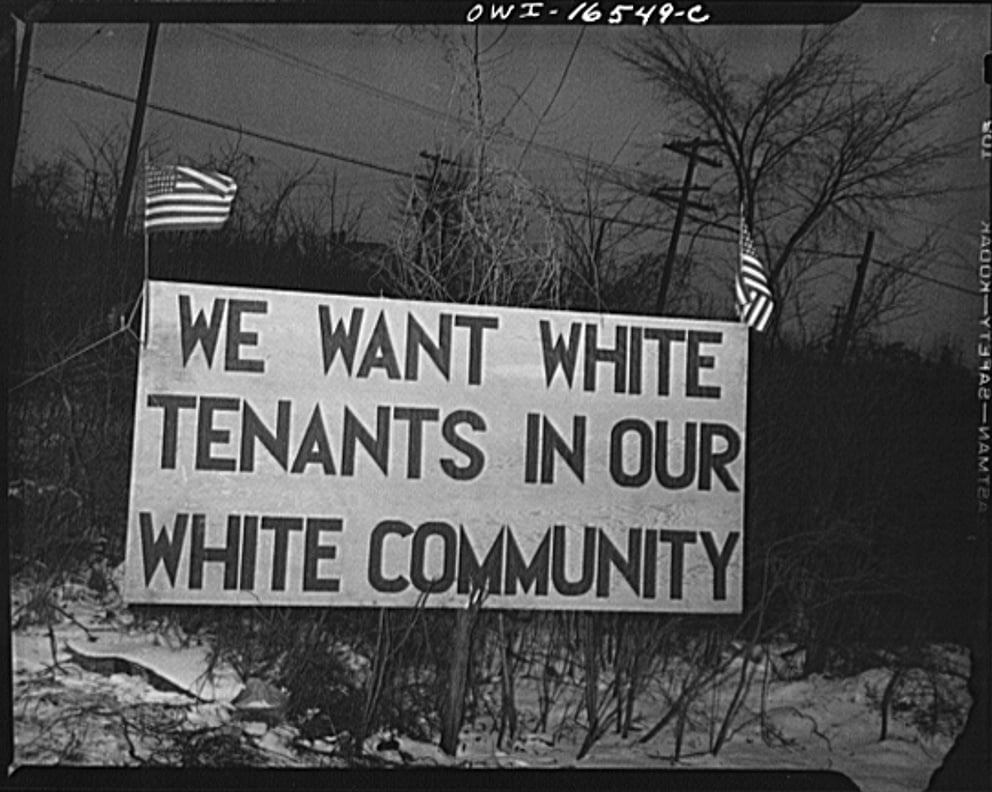

In an NPR interview about his new book The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America, Richard Rothstein discusses the federal government’s intentional structuring of segregated housing after the Great Depression. Lending agencies, developers, the federal government, sales and rental agents, public zoning agencies, law enforcement, school districts, and municipalities collaborated in the 1930’s to deny homeownership to black families while facilitating and subsidizing all-white suburbs through low-interest loans. This deliberate segregation cannot be disputed. We have written, historical proof. We can hold the racially restrictive covenants in our hands and delineate their race-based terms. The interview and the book are on point: while we may wish to ignore or forget it, our history is one of purposeful discrimination, from the top down.

But what is also so often “forgotten” is the reality that the widespread structuring of housing segregation continues to take place today. The federal government, in conjunction with financial institutions, municipalities, developers and a whole host of other private actors, are just as responsible for housing segregation now as they were in the 1930’s.

So what’s the difference between housing segregation then and housing segregation now, particularly as it relates to race?

Its methods—once explicit and unapologetic—are now quiet, latent, and, at times, impossible to see. In short: this brand of discrimination is far more dangerous. And today, as then, it all starts with the federal government.

Between 1934 and 1962, the federal government backed over $120 billion in home loans. By design, 98% of those loans went to white homebuyers. This did more than contribute to segregated housing: it fundamentally shaped its contours.

But today? It’s not as much about what the federal government isdoing with regard to housing as much as it is about what it’s notdoing. Since the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the federal government—under both Republican and Democratic administrations—has given billions of federal dollars to cities and suburbs on the condition that these jurisdictions proactively combat housing discrimination and meaningfully address disparities in housing opportunities. Yet for nearly fifty years, all violations of these conditions have been effectively ignored and communities have received funding streams regardless of their actions. Until the infamous Westchester case in 2013, the only attempt at withholding dollars from a community who was failing to adhere to its civil rights obligations was led by former HUD Secretary George Romney (Mitt Romney’s father) in 1970. Through an initiative called Open Communities, Romney ordered HUD Officials to reject public works applications to cities and states that were utilizing discriminatory policies.Romney’s rationale? Public dollars can’t be used to foster segregation. His effort was swiftly shut-down by then President Nixon—and we’ve hardly heard a peep since.

The failure of the government to enforce this centerpiece of the Fair Housing Act has provided the backdrop for nearly five decades of federally sanctioned segregated housing.

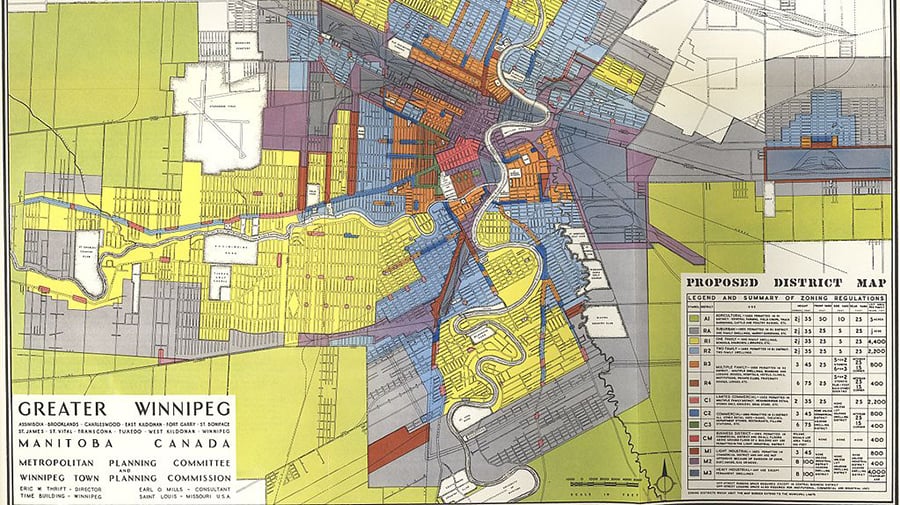

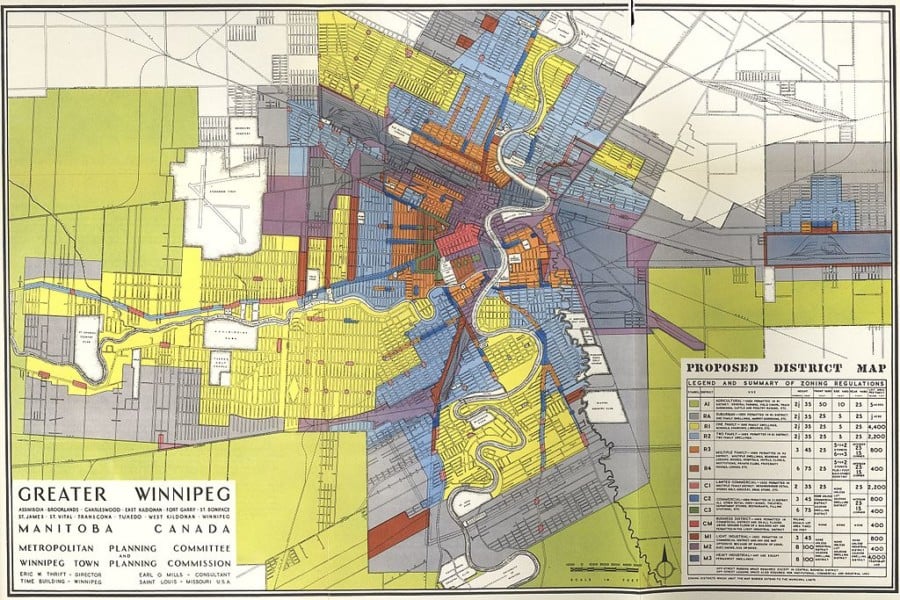

But it doesn’t stop with the feds. Local efforts by city governments play their role in housing segregation as well. Though municipally mandated racial zoning was deemed unconstitutional in 1917, zoning is still being used as a tool to segregate communities across the country. How is a practice outlawed for exactly one hundred years still successfully employed? Two words: neutral language.

For example, single-family ordinances, which zone an area as single-family housing, have been passed in countless neighborhoods across the country—ostensibly so they can avoid the construction of low-cost housing (i.e. apartments). On paper, the purpose of these ordinances is “to preserve the character of the neighborhood.” But as Lisa Prevost so poignantly observes in her book Snob Zones, community forums, local blogs, and internal correspondence often reveal that many of these ordinances are directly aimed at the prohibition of housing that might attract the “wrong” sort of people. In the same vein, density and lot sizes are also used as a means of exclusionary zoning.

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Seemingly neutral language in zoning extends to seemingly neutral policies in the rental arena as well. Tenant selection policies that exclude individuals on the basis of race have been outlawed since the passage of the Fair Housing Act. But policies that exclude individuals (and their families) on the basis of having a criminal record are widely used by the vast majority of public and private housing providers. These policies have perpetuated segregation in quiet yet unparalleled ways.

Since the onset of mass incarceration and the purported War on Drugs in the 1980’s, those with records have been widely excluded from renting apartments of any kind, including publicly owned subsidized units. Given the disproportionate impact the criminal justice system has on nonwhite communities, this exclusion has unduly impacted nonwhite individuals—particularly black men—while contributing to patterns of racial and economic segregation for nearly forty years. In turn, the denial of individuals with records from housing has also been a leading contributor to our country’s soaring recidivism rates and community unrest.

Until the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Inclusive Communities and the recent—albeit long overdue—guidance from HUD, this practice has gone widely unnoticed and largely unchallenged.

To make matters worse, there is another far more sophisticated and insidious mode of housing segregation currently manifesting itself in the lending arena: Algorithms.

In times past, discriminatory lending was carried out primarily through redlining. Established by the federal government and eventually adopted by mortgage lenders, it was common practice to (literally) outline poor and minority neighborhoods with red lines, indicating zones where mortgages would not be made.

But today? The overt practice of redlining has largely been replaced with the nuanced complexity of big data. Algorithms—and the data used to inform them—can be exceptionally helpful, and healthy, when used to facilitate ethical lending practices. Their ability to increase processing speeds, minimize labor costs and reduce mistakes based on human error is invaluable. But as Cathy O’Neil recently queried, what happens when algorithms discriminate?

Similar to the process of underwriting, lending algorithms require human input. And that input, as we are starting to see, is often intentionally (and unintentionally) discriminatory. The effect as it relates to mortgages and homeownership? The continuation of segregated housing patterns.

Though we are not seeing race explicitly built into algorithms, what is being used is mortgage applicants’ source of income. For instance, algorithms have recently been designed to exclude individuals whose income includes any form of public assistance (notably, Section 8 housing assistance). Demographics such as education and zip code are also being used as disqualifying factors, as are an applicant’s use of punctuation, capitalization, and spelling—an obvious proxy for education, but not creditworthiness.

So, yes, algorithms remove human error from the lending process. But they don’t remove human bias. Their aim is to maximize profit and streamline efficiency by any means necessary. But as aptly summarized by Marc Stein, CEO of Underwrite.io, discrimination doesn’t become legal just because it’s done by a machine.

So where do we go from here?

On a federal level, it will take political will from the Trump administration—and all other administrations that follow. Change can undoubtedly stem from local efforts and the commitment of communities as well.

But most importantly, we must recognize the sophistication of contemporary housing discrimination if we have any shot at alleviating it. Segregation is all too often treated as a relic of the past, which obfuscates the ways in which the same forces that designed segregation then have been redesigned to both create and reinforce it now. Addressing segregation as a contemporary problem will allow all us to look more critically at the “plain” language of zoning ordinances, tenant selection policies, and mortgage underwriting. We must identify segregation in its new form while finding ways to remedy it—a healthy and equitable social ecosystem, the future of our country, depends on it.

Emily Hunt Turner is the Founder of All Square, a social enterprise that aims to combat recidivism through a grilled cheese restaurant and institute. She is a housing and civil rights attorney with a background in public policy and architecture. Prior to All Square, Turner worked as an attorney for the United States Department of Housing & Urban Development (HUD).

If you enjoyed this article, check out “This Must Be a Turning Point: Anna Minton on Housing Post-Grenfell.”

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025