September 18, 2017

Paola Antonelli on Her Upcoming MoMA Exhibition “Items: Is Fashion Modern?”

The exhibition, which uses a design lens to explore fashion’s many functional, aesthetic, and social dimensions, will run from October 01, 2017 to January 28, 2018.

On the eve of the Museum of Modern Art’s landmark exhibition on the past, present, and future of fashion, Metropolis‘s Paul Makovsky spoke to MoMA’s senior curator Paola Antonelli about why she chose to put on a show about garments, why Bernard Rudofsky (who curated MoMA’s first show on fashion back in 1944) remains as relevant as ever, and the challenges of selecting fashion objects that have had a strong impact on the world.

Paul Makovsky: Why and how did you come up with the idea for Items: Is Fashion Modern?

Paola Antonelli: I’ve been at MoMA for 23 years now, and I came on board having studied architecture, and having worked in fashion—I was an intern working for Armani’s PR office in Milan. So I was always thinking about fashion. At MoMA, I started to sort of assess the landscape—I saw the Geoffrey Beene exhibition at FIT that blew me away—and I asked Philip Johnson, who had interviewed me for my job, “What about fashion?” And he gave me the official explanation: Fashion is so ephemeral, it’s so dictated by seasons, it really goes against the idea of timelessness that is at the core of the idea of Modern. I just didn’t buy it because he had done the Deconstructivist Architecture show, and there was nothing more ephemeral, more trend-based than that show. I kept mulling it over, then slowly I would inject little pieces of fashion in the collection, but always based on other excuses, like with the Humble Masterpieces exhibition—we added the white T-shirt—or another time we added the Final Home parka.

PM: How did you organize your research for the exhibition?

PA: I kept this list called “garments that changed the world.” I was convinced that you cannot tell a real, MoMA-style history of Modern design and architecture without garments. So fashion is the system and clothes are the pieces inside. I kept this list, and at some point, I was talking about it with the chief curators and MoMA’s director, Glenn Lowry, and he said, “Have you thought of doing the fashion show?” And I said, “Let me try.”

PM: How many items did you finally end up with?

PA: It went up from the initial 250 to 300, and then we scaled it down. Early on we wanted to get to 99, but we ended up with 111. I’m a good generalist and I really know design, so if I can bring things into the realm of design, then I can handle them, but I still have to have somebody else’s help—those fingertips Is Fashion Modern of knowledge of fashion, and the whole life cycle of fashion and the system and the history—to help fill in the gaps. We did a lot of travel, to Australia, Korea, Japan, India, Bangladesh, Nigeria, and South Africa; then we had people in Latin America who were scouting for us, because also we were looking for designers of the prototypes because we also commissioned about 20 prototypes and then eight more we found already made. When I was in India and Bangladesh, for instance, it was really a crash course in textiles and also in labor practices and supply chain management.

PM: Are those issues part of the exhibition?

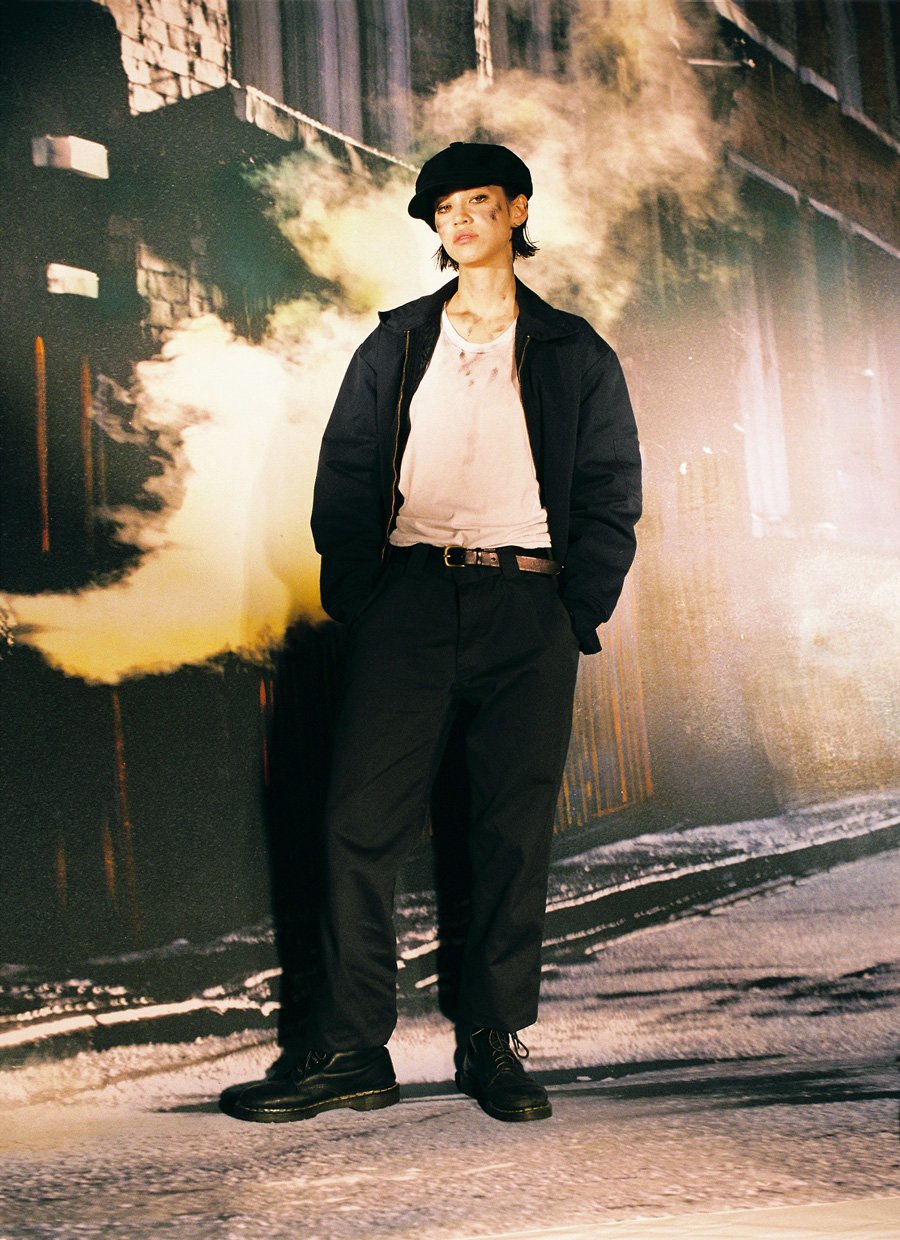

PA: Yes, every single one of these items is a way to enter the system of fashion. There are objects that are more rarefied, like Yves Saint Laurent’s Le Smoking jacket, which enables you to enter the idea of gender and tailoring and also to notice what happened between the late 1960s and today when you talk about gender fluidity. Or if you enter through the 501 jeans, you can learn a lot about the history of America, but also about how the denim industry has a water problem they’re trying to solve. If you enter through the dashiki, you can talk about the PanAfrican movement and how the dashiki was brought to Harlem, and connect it to the Black Panthers, which then connects to the beret. So there are many different ways to look at the exhibition.

PM: Did you look at Bernard Rudofsky’s book and exhibition Are Clothes Modern?, which was done for MoMA during the 1940s, as a curatorial jumping-off point?

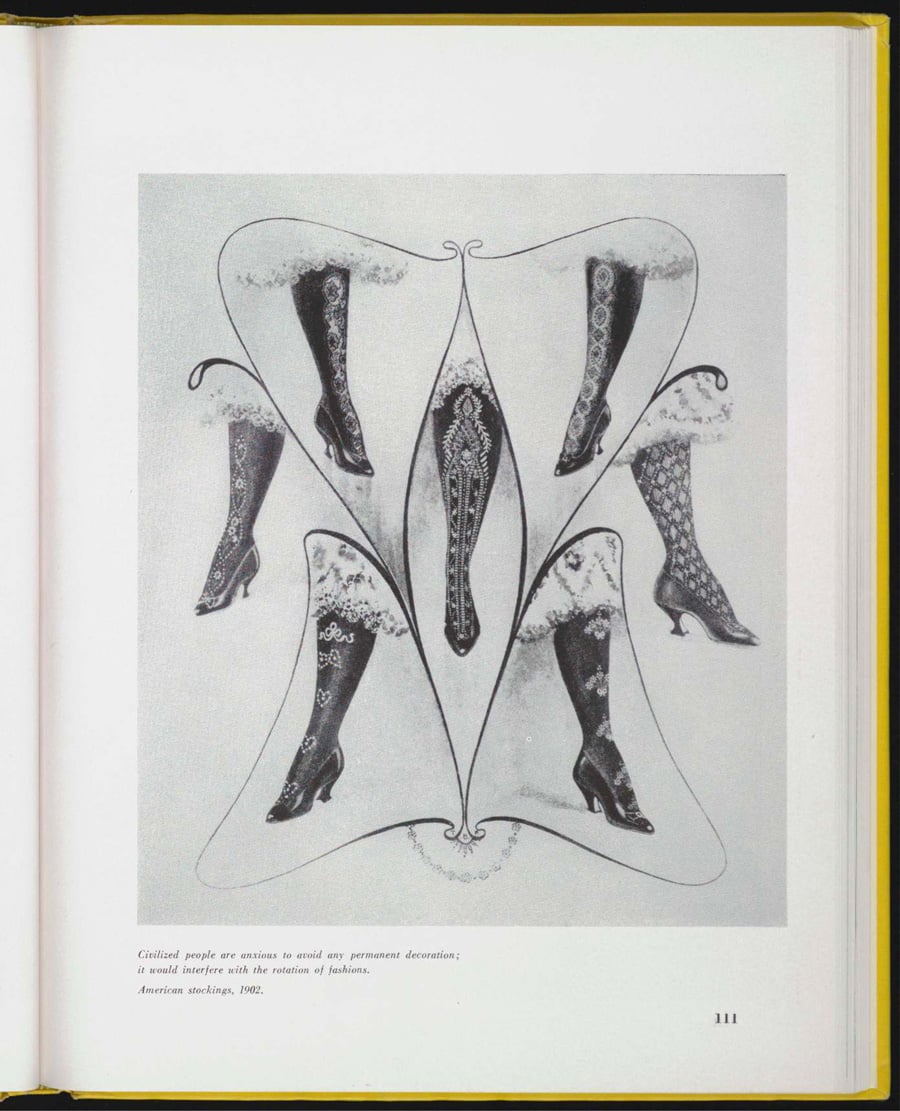

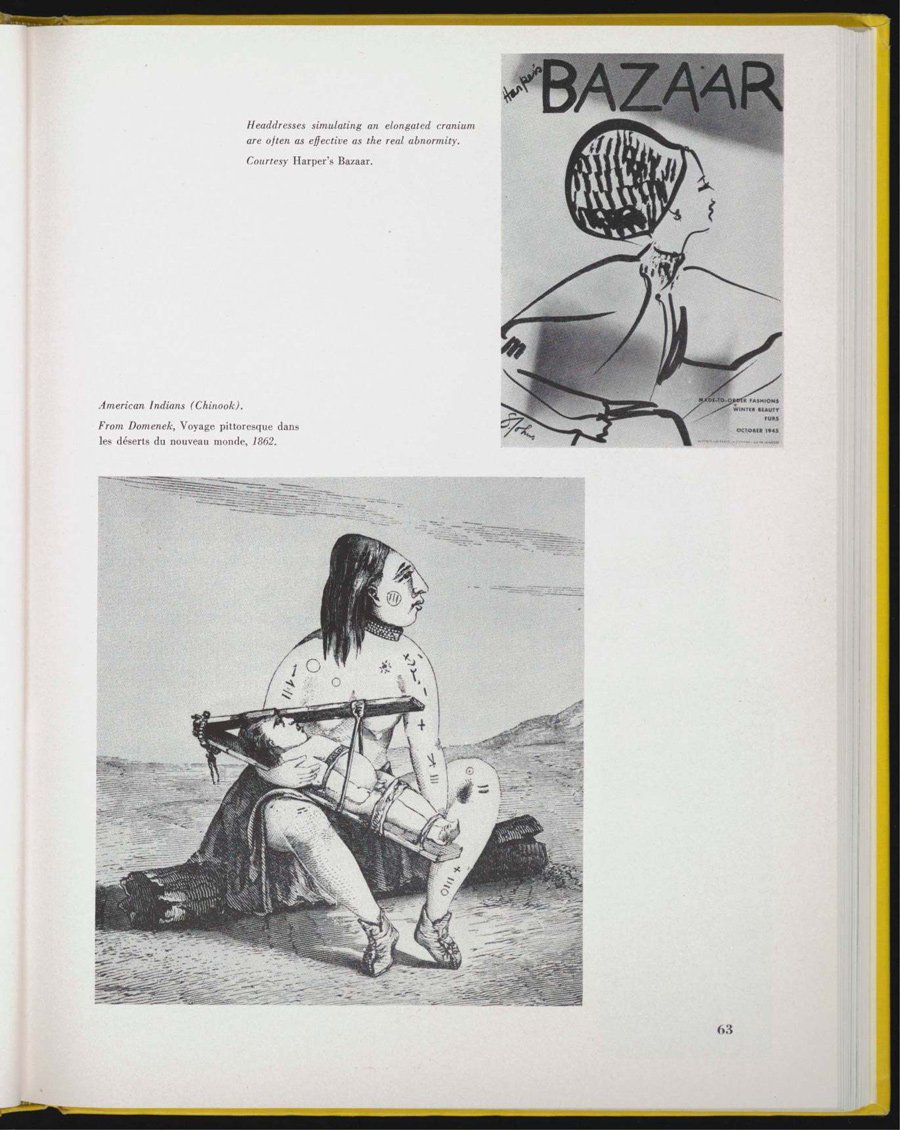

PA: It was a very successful exhibition in 1944, and the book is revered today. But Rudofsky’s book is not about fashion; it was truly about garments and had very few pictures of contemporary fashion, and had instead a lot of ethnographic research. It was a critical work of design in itself.

PM: Rudofsky is interesting, too, because he was not only a writer, a curator, and an architect but also a fashion designer in his own right, designing the Bernardo sandals.

PA: Yes. I knew Rudofsky’s wife, and actually the first thing I ever did when I started as an editor at Domus magazine was write his obituary. I had no idea at the time who he was.

PM: So did you read the book a couple times over?

PA: Yeah, the first time I read it was many years ago, and then I reread it before starting the project. And it struck me as incredibly interesting, but also very arrogant.

PM: Would you say your role is to look at clothing through the lens of design?

PA: I love fashion, but that’s not my job. What I’m good at is to use the lens of design, to talk about textiles, about how and where things are made, and how they enter your life and how they exit your life. Elements like functionality, aesthetic, expression, sustainability, reusability—all the different aspects that are about design.

PM: And neither the exhibition nor the catalog is a linear history of fashion?

PA: The catalog is in alphabetical order. And the exhibition, I consider it to be in an atmospheric climate order, like architect Philippe Rahm, who does those climatic zones. There are no sections with big titles, so you can basically float through it. There are some adjacencies that are done on purpose. For instance, we have a point where we have Comme des Garçons’ Body Meets Dress—Dress Meets Body collection next to maternity clothes. So the idea that your body can be deformed in an interesting way is connected to the idea of maternity clothing, because until the 1950s it was about hiding pregnancy. And there are some really interesting discoveries. For instance, there’s this whole area that is about introversion, rebellion, modesty, and emancipation. The hoodie, for example, is a very charged garment, so it’s by itself. It started off with Champion in the 1930s, and was totally about sports, then it was used by workers on construction sites and cold storage. Then it was collegiate, and then it became on the one hand the mark of hip-hop and skateboarders, and on the other hand Mark Zuckerberg. And then there was the symbology of Black Lives Matter and Trayvon Martin. So the hoodie is about function, introversion, and a sort of rebellion. And near it we have the other really poignant object, which is the black turtleneck. So here, you have the rebellion and also the introversion and also the emancipation and the modesty.

We have a beautiful video from Hana Tajima, the consultant for modest fashion for Uniqlo. She had the tapered turtleneck and she morphed in the video from turtleneck to hijab. She was showing the rebelliousness, the 1960s, the beat generation, and moving into the hijab’s history. It’s subtle and you can just walk through and you see these beautiful dresses, or you can really read and make your own connections. Another example is the burkini and bikini. Now, at different moments in history, there were two different ways to control women’s bodies. And you can find 1950s pictures of the same beaches in the South of France with the police harassing women wearing the bikini, and then last year, the police harassing the women with the burkini. The last section of the exhibition is about power and the suit, from the hard power of Savile Row to the soft power of Donna Karan.

PM: And you end the exhibition with the plain white Hanes T-shirt?

PA: Right. Because today, if you’re wearing a three-piece Savile Row suit, you might be the bodyguard, and the person with the real money and power is the one wearing the white T-shirt. If you consider that every single one of these objects is a way to look at the system of fashion and to have considerations that are more systemic, the white T-shirt has so much.

You may also enjoy “V&A Show Deconstructs Balenciaga’s Masterful Forms.”