February 14, 2018

Three New Books Reveal Why Postmodernism is Back

Don’t call it a comeback. Postmodernism in architecture was always already a revisitation.

Millennial pink, that fashionable and unavoidable hue of a faded rose, was not invented by millennials. It was used back in 1979 by the Miami architecture firm Arquitectonica, adapted from the signature color of Mexican Modernist Luis Barragán, for the glass brick and stucco walls of the Pink House—an Art Deco–meets–Neoclassical villa in which stout palm trees do the work of a Doric colonnade.

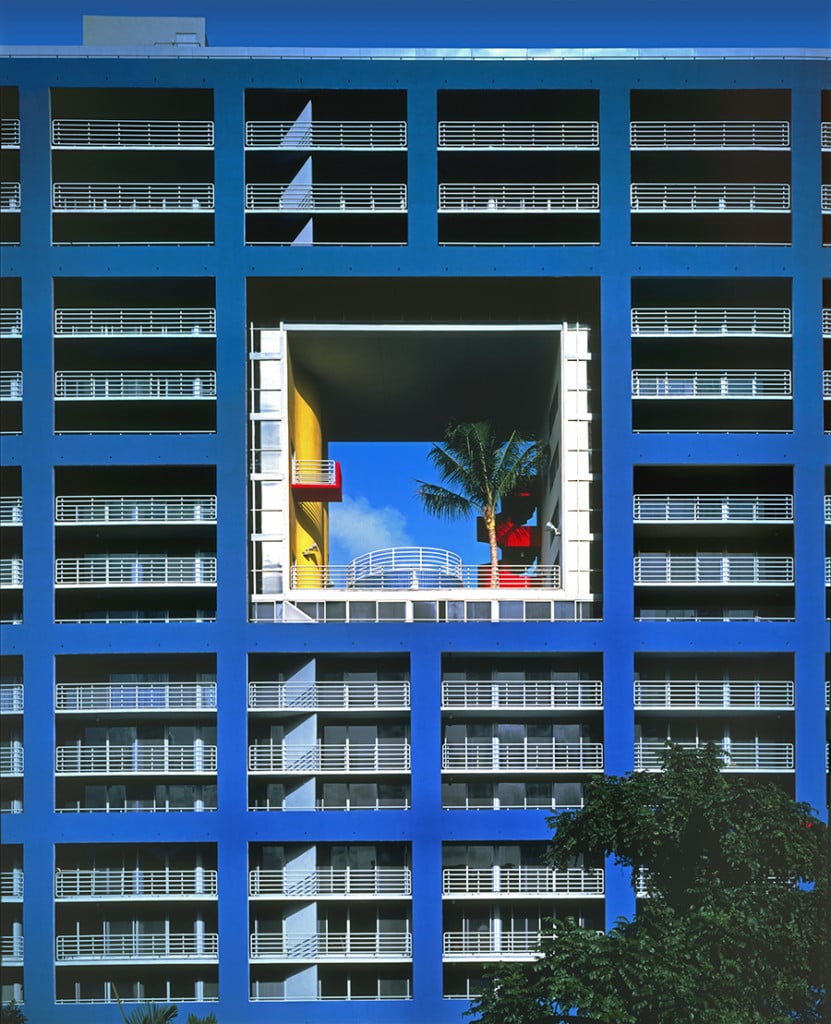

Similarly, today’s trendiest designers and coolest architecture students draw exactly in the style perfected by Arquitectonica in representations of its celebrated 1982 Atlantis condominium complex—the one you see on Miami Vice—in which 45-degree isometrics cleverly resolve grids and semicircles and pyramids, plus squiggly addenda like outboard spiral staircases, into an animated yet orderly composition of pastel purples, pinks, and reds. The Pink House and Atlantis appear on page 154 of the recent book Revisiting Postmodernism (RIBA Publishing) by British architect Terry Farrell with Adam Nathaniel Furman, in which Furman notes of Arquitectonica’s stylish touches, “It was the inexplicable purposelessness and yet wholly intriguing qualities of these elements that caught the popular imagination.”

“After Po-Mo,” Farrell quotes a 2011 observation recorded by architectural historian Joseph Rykwert, “comes Po-Po-Mo. And after Po-Po-Mo—comes No-Mo! So that’s where we now are.” But seven years later—even as some of the movement’s original monuments, like Philip Johnson’s Chippendale-pediment-topped AT&T Building, begin to face their own preservation controversies—the No More of No-Mo seems to have been succeeded by More Postmodernism. Call it Mo-Po.

But don’t call it a comeback. Postmodernism in architecture was always already a revisitation. Advanced in 1960s American practice by Robert Venturi alongside his partner, the theorist Denise Scott Brown, and in 1970s British practice by James Stirling alongside the critic Charles Jencks, it was an artfully high-low synthesis of a scholastic neoclassicism and the appropriated vernacular symbols of midcentury Pop Art. The style seemed to offer liberation from the purposeful forms—still functional as ever, but increasingly and even oppressively conventionalized—of what the Postmodernists liked to call High Modernism, into a forcefully intriguing picturesque. Developers liked it because it added status to buildings that, because their primary effects were visual, not spatial or structural, were cheap. People liked it because it deployed forms—arches, pitched roofs, columns—that offered what historicist architectural styles have, since the original revivals of the 19th century, always provided: the efficient poignancy of nostalgia, the comforts of the familiar, the feeling of restoring a glorious past.

Mo-Po’s revivals of Po-Mo’s revivals are especially lively in the United Kingdom, where such young practices as Assemble, Public Works, and vPPR are unafraid of a pitched roof. The jolie laide work of Fashion Architecture Taste (FAT), such as the now-disbanded group’s gingerbread-like House for Essex of 2015, polemically explored the outer limits of good taste. Perhaps this was to counterbalance the ponderous quasi-classicism of architects Quinlan Terry and Léon Krier, whose stylized mannerisms, like those of the New Urbanists in the United States, coincided with—but were not essential to—a worthy interest in pedestrian-scaled streetscapes, wayfinding, and communal life with which, much to their reputational benefit, they became associated. On Terry and Krier their contemporary and less doctrinaire British Postmodernist John Outram remarked, “I used to like modernism but wanted to make it usable, unlike the double-breasted Doric Brigade.”

That observation appears in a new survey by Geraint Franklin and Elain Harwood, Post-Modern Buildings in Britain (Batsford), a useful guide not only to a formerly uncelebrated built legacy of the 1970s and ’80s but to the insular and internecine maneuvers behind that sceptered isle’s battle of styles—including the expert shade thrown in Revisiting Postmodernism. Farrell co-opts Postmodernism’s seeming opposite, the High Tech innovations of Richard Rogers: “After the somewhat bombastic…Pompidou Centre (1977), which so overstated functionalism that it became a very knowing decorative form, he has succeeded in producing much more plastic, humane and delightful projects.” Farrell offers faint praise for Stirling’s canonical No. 1 Poultry building in the City of London as “perhaps not his best, but…a complete and consistent piece of work that very much carries on the language he had developed and relaxed into.” Franklin and Harwood recount how from 1965 to 1980 Farrell was a design partner of Nicholas Grimshaw, who along with Rogers, Michael and Patty Hopkins, and Norman Foster would establish the High Tech movement, which is Britain’s most substantial contribution to global architecture culture since postwar Brutalism; and how, prior to Stirling’s commission for No. 1 Poultry, Farrell had developed his own unbuilt proposal that creditably preserved the actual historic buildings on the site.

The course of architectural history, being shallow and narrow, is more swayed than History itself by the big personalities that the design world tends to attract. But historians of architecture, especially those of the Postmodern moment, seem to prefer to evoke impersonal epochs, forces, and cycles. In his introduction to Postmodern Design Complete (Thames & Hudson), a new and essential encyclopedic compilation of architecture, graphic design, and the decorative arts by Judith Gura, Charles Jencks asserts, “The proclaimed demise of the movement was simply a misunderstanding. Postmodernism hasn’t been revived; it never left.” Gura’s selections—everything from 1980s Aldo Rossi to 1990s Frank Gehry, from Venice, Italy, to Venice, California—reflect the radical pluralism that was part of Postmodernism’s appeal, but run the risk of proving Jencks’s assertion only with the tautology that if Postmodernism can be almost anything, then it can’t ever go away.

But what is the special appeal to millennial architects of the colors and features first perfected in the years of their birth? A basic answer may lie in the recursive fashion cycles to which architecture, for all its pieties and duties, is subject. But part of the answer may be new. In the age of Instagram and Pinterest (a platform famously devised by an architecture grad), the visual stimulus of Postmodern conventions, designed primarily around appearances, lends itself to pictorial reproduction and its theme-and-variation iterations to cascading successively through feeds.

Gen Xer that I am, I asked a smart millennial—Ricardo A. Leon, a designer and visual artist whose fine-art prints deploy and subvert Mo-Po tropes—about it. He said, “There is something parallel between the way meme culture has spread online and these Postmodern drawings. Memes are powerfully simple and they are best described as an inside joke. The success of a good meme is in something you immediately understand, but the joke has an alternate relevant meaning that no one explains. Also, it’s beautiful.” The accessible not-quite-mystery and the meta cross-references of Postmodernism’s image cache may explain something of Mo-Po’s seemingly exponential rate of production and distribution. Conversely, the solemnity and materiality evoked by a quasi-classical arch or a stone texture in those images offer a seeming tonic to the ubiquitous capacitance of the phone screen. But also, with its visual volubility and the symbolic storytelling of which its advocates believe it capable, “Postmodernism, it seems,” in the words of a much-circulated essay by contrarian FAT cofounder Sean Griffiths in which he disavows his former style, “won’t shut the fuck up.”

The risk is that while our times may call for a sense of humor, they may not be best served, in the built environment, by mere wit. Postmodern work, at its most trivial, relentlessly signified a sense of place while consistently failing to provide it. Postmodernism’s founders were aware of this. “In about 2000,” Denise Scott Brown says in her afterword to Postmodern Design Complete, “a new generation of architects began to reconsider Postmodernism as we defined it…. [T]he story of Postmodernism is not complete. [But]…it reflects the [Modern] movement’s brave objectivity, its good causes, and its intention to draw art from hard reality. And although postmodern rule-breaking is sassier, it’s pushed by the same high aims.” At its best, the legibility and narrative quality of Postmodernism may present a way of seeing the world more clearly, and not only through rose-colored glasses.

You may also enjoy “

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025