May 24, 2016

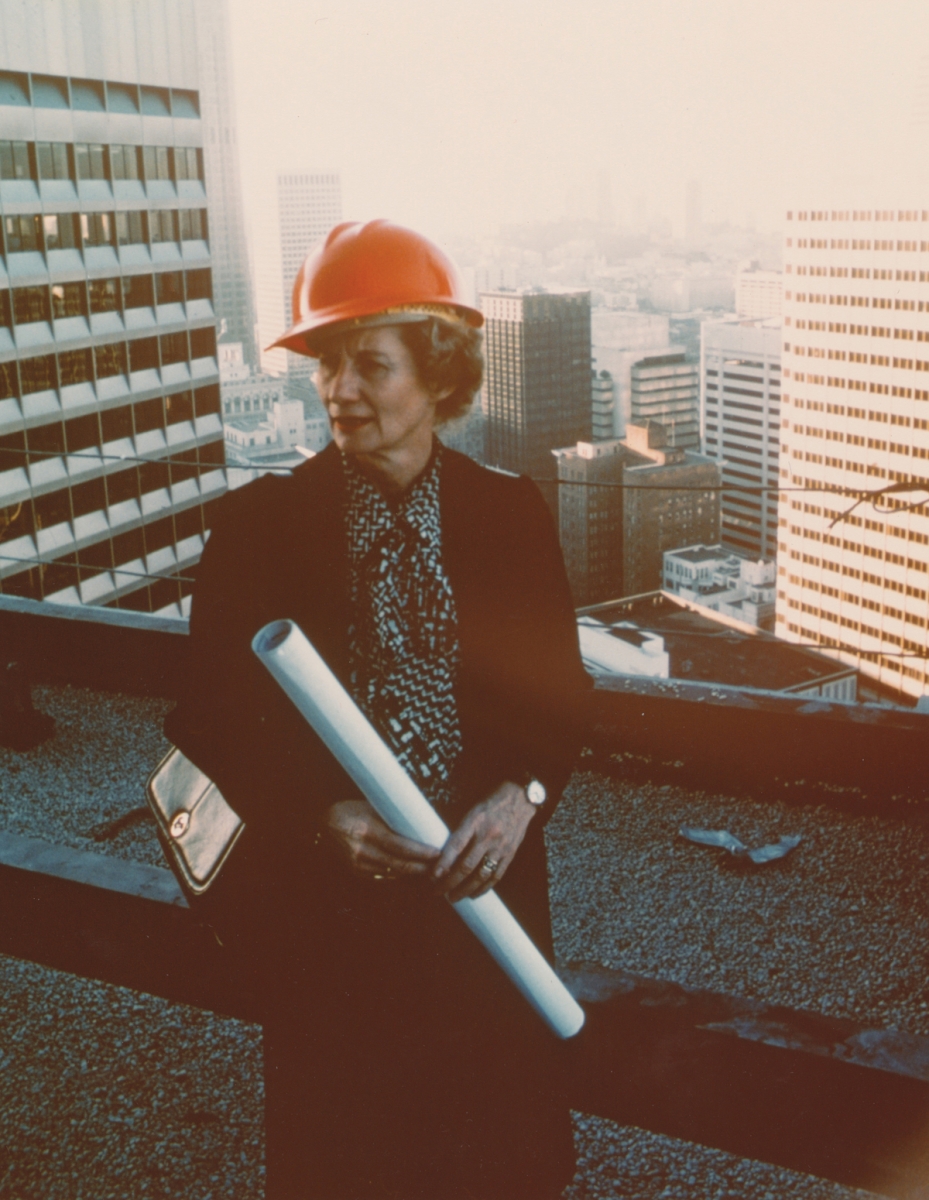

Q&A: Beverly Willis on Finding Design in Everything

The architect-designer discusses her long career and mulls over her influence in fields from art to software design.

The following is an excerpt from Twenty Over Eighty: Conversations on a Lifetime in Architecture and Design by Aileen Kwun and Bryn Smith, published by Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

You’re a self-made woman who has pioneered many initiatives: first an art atelier, then an industrial design firm, an architecture firm, a think tank, and a foundation. What drives your passions?

I was not a person who knew what they wanted to do at a very early age. My ambition in life was to be independent. I read this wonderful book as a child, the title of which escapes me, but the author’s background felt similar to mine. She didn’t like the situation she was in (nor did I), so she found something that she could do: in her case, catching butterflies, which she sold to people in her neighborhood to earn money to become able to do what she wanted. I figured, I’ve got to find something like that; maybe I could make things with my hands. Once I discovered art—painting, drawing—it was everything. I became completely absorbed in it.

You first began working in art, then later transitioned to design. Do you distinguish between the two?

I don’t. I think there’s design in everything—even a good program, like a roundtable, takes a lot of what I consider design. All aspects of design are important and useful. The most successful people are good designers, even though they may not be in art or architecture.

When did you first become interested in design?

I was born in Oklahoma, and the only environment I knew before the age of six consisted of oil fields, which were grim places. There was no landscaping—just barren and totally flat. Very few sidewalks, no parking regulations, no organized streetscape.

This was also the era of the rise of the industrial designer, when everything was perceived as needing design work, whether it was a teakettle, or salt and pepper shakers, or a chair. I was really bothered by the lack of design in Oklahoma. Why? I don’t know. I hadn’t experienced designed things, hadn’t been to Europe. But for some reason, I perceived Oklahoma that way and hated it. It was only much later that I thought I could do something about it.

You had an adventurous youth, becoming a licensed solo pilot by the age of 18. How did growing up during wartime influence you?

The era in which I was born gave me a fearlessness, and to some degree an aggressiveness, that came from being instilled with the idea that you might have to fight for your life. I was in high school during World War II, and the government wanted everybody to learn survival skills because there was a great sense—at this point I was in Portland, Oregon, a big ship-building city—that we were going to be invaded. They wanted us as individuals to be equipped: not necessarily to fight the enemy, but to survive. I built a radio. I learned wiring and welding. These were things I practiced as part of the war effort. So I had a very early and robust introduction to a lot of tools that actually had to do more with architecture than painting or art.

It seems to have greatly shaped your work ethic.

Also as a result of growing up during this time, I became adept at rallying and creating organizations. I am a cofounder of the Women’s Leadership Council of the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture, for example. All I had to do was make two telephone calls to create that.

Creating the National Building Museum, on the other hand, took five years. There were many people involved in that project. What motivated me was a feeling that carried over from the war: I looked around the world and saw that four or five other nations had such a museum. Why shouldn’t we also have a facility dedicated to celebrating the work of artists and designers, architects, engineers, and urban and transportation system planners, not to mention builders and laborers? They’re the ones who are actually out there with the tools, building the buildings. To create a place where they would be honored or represented struck me as a huge national need.

How would you describe your approach to work?

I’m a believer in research. And I have an ability to connect the dots, which some people do and some people don’t. These two aptitudes continue to inform my approach to anything. Also remaining fairly current on what’s going on. I may not know how to use a particular software program, but I’ll know about it—what it does and how it fits in.

You were one of the first architects to experiment with computer-aided programming. CARLA (Computerized Approach to Residential Land Analysis) was custom-developed by your firm. Were there other similar software programs in use at the time?

Not in architecture or planning. CARLA had its genesis in World War II. The government developed a little piece of 3D software for the bombers on planes that actually drew the bombing site, to improve accuracy. We picked up that software and adapted it for the placement of housing concepts on land.

How did the development of the software come about?

We were motivated by need: How do you plan a building site that’s a hundred or even a thousand acres? When I entered into the architecture and design world, all the firms were essentially one person with a couple of drafting assistants. Even a firm the size of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill only had, maybe, 20 people. It was because the projects were relatively small. A skyscraper in those days was 12 stories high; that was a huge building that cost a million dollars. A site was never larger than, say, a block. So you could walk around it, and indeed, that’s what you were taught in school: to walk around a site to get a sense of it. That was considered good design.

But you can’t walk and memorize a hundred-acre site. The postwar suburbs were on the rise. Developers were acquiring 500 acres of farmland at a time and building whole clusters of housing units. We felt we needed a tool to help us analyze the land.

At the same time, we were reading stories in the newspaper about people’s lives and houses being lost because of mudslides and flash floods that were in part a result of builders moving land around. That’s not done anymore; we’ve become smarter and wiser. But back then, that was one of the big issues. I had the idea that if I could put together an automated system that enabled us to analyze the topography, we could then easily decide where to put things. The whole point was to minimize the cutting and filling. The less you move, the safer it is, and the more money you save.

I knew Harvard and MIT were playing around with computer concepts, so I approached one of the people at Harvard, hired a consultant, and found the graphic software program at Kansas State Geological School. We put it all together. Suddenly we could do six months of work in 15 days, with greater accuracy than anybody else. So when the military wanted to build a new town of 11,500 people in Hawaii, we beat out all the big firms in the United States because we were the only ones who could get the approvals to do the job on five hundred acres of unstable soil.

This text was excerpted from Twenty Over Eighty: Conversations on a Lifetime in Architecture and Design (Princeton Architectural Press, 2016) by Aileen Kwun and Bryn Smith.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025