January 16, 2015

Q&A: Landscape Architect Anne Whiston Spirn on Nature and Cities

An interview with the designer and author on the release of her new book, The Eye Is the Door.

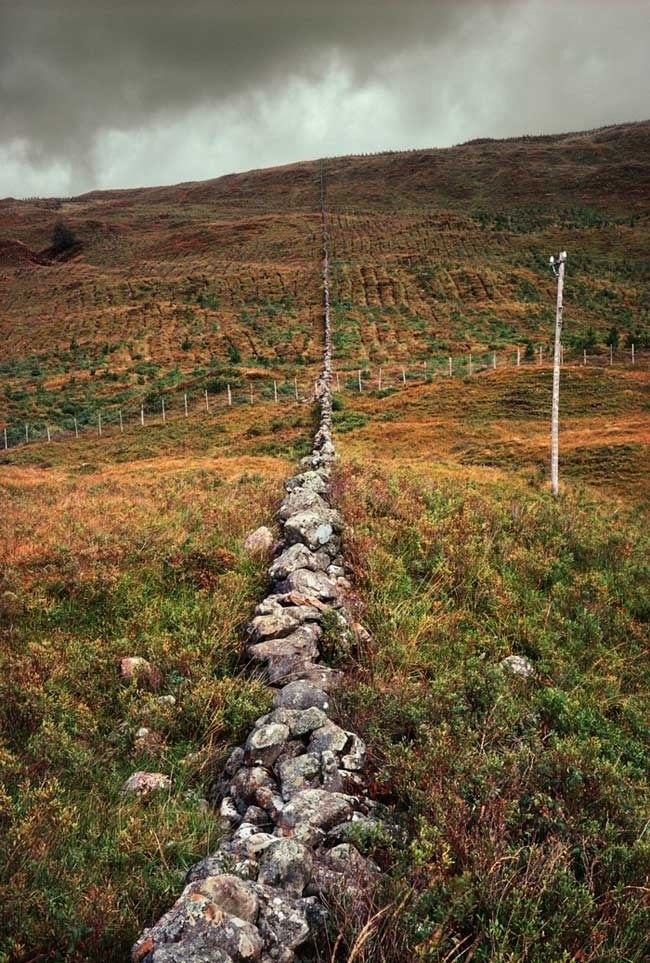

Glen Loy, Scotland

All photos courtesy Anne Whiston Spirn

Anne Whiston Spirn, FASLA, is a professor of landscape architecture and urban planning at MIT. Her most recent book is The Eye is a Door: Landscape, Photography, and the Art of Discovery (2014). She is also the author of The Granite Garden (1984 ASLA President’s Award of Excellence), The Language of Landscape (1988), and Daring to Look: Dorothea Lange’s Photographs and Reports from the Field (2011 ASLA Honor Award). This interview was conducted at the ASLA 2014 Annual Meeting in Denver.

Jared Green: This year is the 30th anniversary of your book, The Granite Garden, which argued that cities are part of nature and should be designed with nature. Since 1984, how much progress have we made? Where are we still going wrong?

Anne Whiston Spirn: We’ve made enormous progress, particularly with water. Ironically, we’ve done less well on climate and air quality. I say ironically because there’s so much awareness of climate change these days. There’s been a lot of attention paid to design proposals aimed at adapting to rising sea levels, but less to the enormous potential that the design of cities holds for reducing the factors that contribute to climate change in the first place. We need to truly reimagine the way we design cities.

Scientists and engineers are focused on technical solutions, social scientists on policy. And that’s where the public debate is focused. We designers and planners are not getting our message across as well as we should.

On the other hand, it’s a tremendous challenge for us to keep up with the latest and best scientific knowledge that would directly affect the way we design. We’re awash in information. You can’t expect a practitioner to stay abreast of all this literature, which is why we at MIT are proposing to do a monograph series on knowledge related to the urban natural environment — air, earth, water, ecosystems — and make that bridge to design. These monographs would be authored by teams of designers and scientists.

We hope to make these available at no cost, to anyone in the world. We hope that they’ll be valuable to scientists too, because most scientists don’t really know how their discoveries apply to design and planning. We are seeking funds to start with urban climate and air quality and then do our next monograph on water.

My hope is that this will prompt new experimentation and research that will give landscape architects the information we need. Right now, scientists develop their research agendas for their own purposes, mainly to document, record, and predict, but not to alter the world or make it more beautiful.

Thirty years ago, there was a sharp divide between proponents of ecological design and landscape as an art form. Examples of urban design that were both ecologically functional and artful were few and far between. I wrote “The Poetics of City and Nature: Toward a New Aesthetic for Urban Design” in 1988 and my book, The Language of Landscape, to argue for design that fuses ecology and art. Others made that argument, too. Now we have many great models of artful ecological design. So that’s another area where we have made real progress.

JG: What do you think of the theoretical discussions born out of your book: ecological urbanism and landscape urbanism?

AWS: They’re very important in several ways. Both movements have appealed to architects, and that’s really important. Green infrastructure is something that landscape architects have been talking about for many decades, but architects weren’t thinking in those terms. Landscape urbanism and ecological urbanism were deliberately aimed to capture that audience. And that’s good. On the other hand, some proponents have claimed their approach is radically new, which it is not, and have ignored the contributions of many others to both theory and practice. Certain built projects have captured the public imagination, but for the most part, the landscape urbanism and ecological urbanism literature has been aimed at the design disciplines, not the larger public. There is a need for publications that are valuable to designers and planners and are also challenging, interesting, and enlightening to a broader audience.

I first set out to accomplish that with The Granite Garden. It probably took me an extra 3-4 years to write the book because I had to learn how to write to this larger audience, use no jargon, and explain the concepts in a way that wouldn’t be boring to my professional colleagues but at the same time would be engaging to the public. I learned the power of that approach when The Granite Garden was reviewed in The New York Times Book Review, The Washington Post, The Los Angeles Times, Christian Science Monitor, and then abroad. It was picked up so widely because it was published as a book for a general audience, not solely as a professional text.

Landscape architects are not doing a good enough job at reaching that broader audience.

JG: You say some things have improved; some haven’t. How would you change the way we’re communicating today? What’s the best way to reach the public?

AWS: The Web and electronic publishing have opened up powerful new opportunities. Twenty years ago, in 1995, the West Philadelphia Landscape Project Web site was in the works. Within two years, we’d had millions of visitors to the Web site, from 90 countries. This is the extraordinary power of the Web. I maintain several web sites, all geared to both a professional and a general audience, related to my research, writing, and teaching.

At AnneWhistonSpirn.com, I make available all of my writings except my books. I retain copyright and distribution rights to my articles, and so I can make them free for download on my web site. All of my courses have been online since 1996. They’re all available at no cost.

I’ve been part of the open-access movement before there was an open-access movement. I’ve always wanted to reach the broadest possible audience. There’s no single way to reach the public, but we shouldn’t dumb things down. We can engage both professionals and the public, if we go beyond the PR stuff and really try to reach the public in a serious way. As my editor would say, “Anne, your readers are not like your students. They don’t have to read. They can go get a beer and put down your book and never pick it up again, so you have to keep them engaged. You have a duty to your reader.”

E-publishing affords new ways to expand readership. With its many color photographs, a print edition of my new book, The Eye Is a Door: Landscape, Photography, and the Art of Discovery, would have been priced beyond the reach of many readers. To make it affordable, I composed and published it as an e-book.

New e-book editions of The Granite Garden and The Language of Landscape will be published later this year. You will be able to read them in two ways: through verbal text (with links to images and captions) or as an essay of images and captions (with links to the book’s text). I envision this as a new kind of reading experience.

Buried Floodplain in Mill Creek, West Philadelphia / Anne Whiston Spirn

JG: Looking at the innovations today, what do you see 30 years ahead?

AWS: In the epilogue to The Granite Garden, I imagined two visions of the future: the infernal city and the celestial city. A lot of what I envisioned then is now commonplace. On the other hand, much has happened that I did not imagine. A lot can change in 30 years. Just think: the original Macintosh, the first personal computer with a mouse and graphic interface, was released in January 1984, the same month as The Granite Garden.

Today, we have the Internet and social media. Our phones can collect and upload all kinds of data. We’ve got crowd sourcing of data. 30 years down the pike, clothing, and vehicles that gather data will be commonplace. We’re going to be overwhelmed with data, so we need to be even smarter about figuring out what this data means and how to use it.

Climate change and the gross disparities in economic means and access to education and employment across the world are threatening the human species. They’re equally threatening, and social upheavals can only get worse as disparities in income and opportunities continue to get wider. Many people won’t have anything to lose. They won’t have a stake in society.

For the past 30 years, since I wrote The Granite Garden, I’ve focused on restoring the natural environment of cities at the same time as rebuilding inner-city communities and educating and empowering young people who don’t have access to a high-quality education that will set them up for having a stake in society. Those are areas where I’ll continue to devote my efforts.

JG: What has the last 30 years of your work with the West Philadelphia Landscape Project taught you about achieving social justice through environmental action in cities?

AWS: The West Philadelphia Landscape Project, which builds on work I did in Boston from 1984 to 86, has been an investigation into how to improve environmental equality and social equity at the same time. There are obstacles, but I’ve learned that it’s not difficult to conceptualize issues and mobilize people. Then it’s just a matter of lining up the resources and getting the administrative framework in place. It’s possible. There are many great examples. In Philadelphia alone, there are many, from the Urban Tree Connection at the grassroots to the city government’s Green City Clean Waters program.

Designers are optimistic. People don’t go into landscape architecture to create a worse world or even to maintain the status quo. We are in this business because we want to make the world a better place. I’m really worried, but I also believe we can do it. It’s possible.

JG: Much of your writing and photography has been focused on learning how to “read” a landscape. What do you mean by this phrase? How is that different from seeing a landscape?

It’s like the difference between merely looking at a picture and understanding how it was constructed and what it means. Landscapes are full of stories. There are natural histories: stories about how a place came to be in terms of its geology, climate, and plants. There are also political stories and folk stories and stories about memory and worship. People’s gardens hold their own stories. In shaping landscape, individuals and societies express their values, beliefs, and ideas. All these stories are embedded in landscape, and they can be read.

Landscape literacy – the ability to read and tell such stories – is fundamental to being a landscape architect. I wrote my book The Language of Landscape because I realized that lack of fluency in the language of landscape was a barrier to more fluent and functional design, more expressive design, more eloquent design.

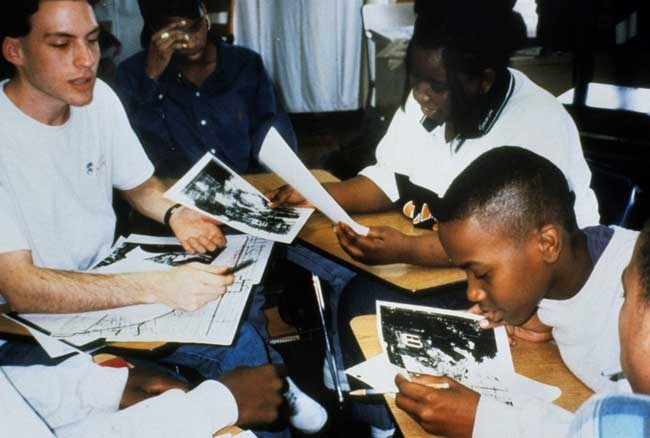

The West Philadelphia Landscape Project was a laboratory for working out ideas about the language of landscape and landscape literacy. It was extraordinary working with 12- and 13-year-olds in Mill Creek, a low-income African-American neighborhood in West Philly, as they learned how to read that landscape.

JG: So what was the best way to teach these kids landscape literacy?

AWS: Their neighborhood was called Mill Creek, but there wasn’t any creek you could see. My students showed them old maps, photographs, and other kinds of documents that described the neighborhood at different historical periods from pre-colonial times to the present. Each week was a different period. Gradually, they came to understand through looking and investigating these old maps, newspaper articles, and planning documents that there was once this creek, Mill Creek. They found out that it was buried in a sewer and that there were cave-ins over the sewer. That’s where a lot of the vacant lands were, including in blocks right around the school. The creek literally flowed right alongside where the school is located.

The children also learned about socioeconomic issues of the 1930s and political decisions that led banks to stop lending money for small businesses and home mortgages in their neighborhood. And they came to understand that their neighborhood today is the result of all these things that happened in the past.

Then they took the historical maps and went out to compare them with the present neighborhood and discovered: “Oh, my goodness, this huge vacant lot block was once six blocks, and there were houses here,” and, “Oh, my gosh, there’s a fire hydrant in the middle of these woods that grew up on these lots.” It really turned their whole attitude about their neighborhood around.

Learning Landscape Literacy at Sulzberger Middle School / Anne Whiston Spirn

Before learning to read its history, the children didn’t believe their neighborhood could ever change. When my students had asked them how they would like to see their neighborhood in the future, they had said, “Nothing’s going to change.” They were very cynical. After learning about its history, they began to say, “The neighborhood could change. It hasn’t always been the way it is. It could change in the future. Why couldn’t it? We know how it’s changed in the past.” Using that knowledge, what kinds of policies and actions could lead to change in the present?

About that time, I started reading Paulo Freire, who was a Brazilian community organizer. He developed literacy programs, for adults in poor, informal settlements in Brazilian cities. His findings about verbal literacy were exactly the same findings I was having in landscape literacy. He found that the most effective way to teach literacy was to collect oral histories of older people in the community, put them into text, and then teach people to read from those texts of the oral histories of their place.

So these kids were learning to read from the primary documents about their own neighborhood. The landscape itself became a primary document. They then became ambassadors. As a 12-13-year-old, to know more than the adults know is tremendously empowering. They went home and told their parents, “Guess what? This happened here and that happened there. See where that vacant land is? There was a creek there.” This is landscape literacy.

If I were working with those kids today, I’d also have them out taking photographs. My new book, The Eye Is a Door: Landscape, Photography, and the Art of Discovery, is a guide for using the camera as a tool to discover the stories that landscapes hold. Through photography, I want to inspire people to look deeply at the surface of things and beyond to the stories landscapes tell, the processes that shape human lives and communities and the earth itself. To pick up a camera and use it to see, think, and discover.

Syndicated from The Dirt, the blog of the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). The Dirt covers news on the built and natural environment and features stories on landscape architecture.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025