February 2, 2016

Q&A: Writer Luc Sante on Paris, Nostalgia, and the Neoliberal City

The writer and critic reveals his nostalgia for an older Paris, mourns the city’s disappearing café culture, and touches on the urban defects of neoliberalism.

A flea market scene in Paris from around 1910

Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

The Other Paris (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015) is a tour-de-force history of the French capital’s nonconformist side, a trip through bohemian dwellings and dance halls along the city’s tangle of streets. But it is also a potent reminder of what cities have lost in their quest for development. Sante, the award-winning writer and cultural commentator who wrote the book, spoke to Metropolis’s Paul Makovsky about nostalgia, Paris’s vaunted liberalism, and the difference between a good life and a secure one.

Paul Makovsky: Few cities have been written about as much as Paris. How did you go about writing your book without repeating what has already been said?

Luc Sante: My immediate impression on first getting the assignment was “They want ‘low-life’ Paris.” Then I proceeded to forget about this for a couple of years, so my hair went gray trying to figure out how to write a book about Paris that wasn’t like the other thousands of books about Paris in English. Ultimately, I just realized that low-life Paris was both what didn’t already exist in books and what I was best equipped to write about. I’m drawn to the history of the working class for personal reasons, because that’s where I come from, but also because, in the case of Paris, that’s what’s been removed from the city.

PM: And that became the jumping-off point?

LS: Yeah, I decided that I wanted to write the history of the working and criminal classes after the revolution [in 1871]. The book is not chronological, but it does begin after the fall of Napoléon III, and it stretches its tentacles as far as the 1970s, the other terminal date being the destruction of Les Halles.

PM: Why do you see that as the cutoff point of the history you were telling?

LS: Les Halles was the center of the city for so many people in so many ways—it was the connection of the city to the natural world, it was a source of jobs, a source of food, and really the beating heart of the whole enterprise. When bureaucrats in the government decided to get rid of it, which happened in 1959, they were really declaring that the interconnectedness of all these things was no longer to be, the city would now exist as a dot on the map, and it would not be a complete ecological system any longer.

Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

PM: But the city is now trying to redevelop that area entirely.

LS: Yes, they’ve done that several times. Les Halles was a great market—the central market where farmers brought in their produce—but also it was this incredible architectural entity, with these cast-iron pavilions built by Victor Baltard in the mid-19th century. They can’t be reconstructed because they were melted down. One of them is now in France, the other is in Japan.

PM: You mention a number of historical personalities throughout the book, such as the entertainers Fréhel and Damia. Who was the most fascinating of these, in terms of your research?

LS: I did absolutely fall in love with the singers. Everyone’s heard of Edith Piaf and she’s wonderful, but she comes out of this big tradition that begins at the end of the 19th century and flourishes right up to World War II. These singers had larger-than-life personalities, and sang about the kinds of subjects that you really don’t see much in America—crime and drugs and imprisonment and prostitution, a lot of grim subjects, as well as happier songs, too. Authenticity was a major selling point of these songs. Fréhel, for example, was young and beautiful, had a music store and many lovers and all of that, and then she got herself addicted to various drugs and was kind of exiled from Paris during the war because she couldn’t travel. When she came back, five years after the war, she had grown obese, but she was comfortable with herself. She gained an additional aura of authenticity, she was really the people’s singer more than any other, and she was a vivid presence in the movies of the 1930s and ’40s. Oh gosh, I have so many characters like that in this book!

PM: Did you feel yourself becoming nostalgic while writing the book?

LS: Yes and no. It’s never entirely clear what people mean when they say something is nostalgic. There’s a lot of use of that term—when you’re interested in the past, you’re nostalgic, because our duty is to the future. You get this a lot from believers in technology, and nostalgia becomes this way of dismissing the fact that we have a past and that the past is interesting and that there are many things that were dumped alongside the road in the great race toward progress that really deserve to be picked up and examined. It’s true that this does involve some nostalgia for me. As I mentioned, I’ve spent a lot of time in Paris over the years. I remember Les Halles—I don’t remember it well, I was only a kid and a visitor—I definitely remember when you could just hang out in cafés all day long, including some cafés that have become rather famous and prohibitively expensive. I remember when, and this was true of all of the cities in the world, you could get a really good meal for three or four bucks.

I do have a section in the book about people lamenting the past and how everything was better before, and you can trace this back to the middle of the 19th century, before [Baron] Haussmann. But I do believe that a real nerve was touched, or rather a blood vessel burst, around the early 1980s, which is when neoliberal economic ideology became policy. It started in different times and in different places, with the elections of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher—it happened a tad later in France, but the ground had been prepared earlier. I think that was actually a betrayal. I know that there’s a lot of people that would not have liked a lot of the physical conditions of my life when I lived in New York City in the ’70s—the rats, the crime, the drugs, the junkies—but nevertheless, you can’t deny that there was this central feature of the city, which was that everyone could live there if they wanted. Now they can no longer do so, and that’s true with close to every major city in the Western world.

The Outskirts of Paris, a painting by Vincent van Gogh from 1886.

Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

PM: What myths and stereotypes about Paris did you find, in your research, to be false or inaccurate?

LS: One thing that leaps to mind is that Americans of all political persuasions have this view of Paris as the capital of liberalism, this hotbed of liberal notions. The fact is that a lot of left-wing notions have taken root in Paris, as did a lot of anarchists, but it’s really been contested terrain, and with just a casual glimpse into the history of Paris, you’ll find as many colorful right-wing cranks as left-wing ones. The pendulum has swung back and forth regularly, and there were a lot of right-wing bohemians, right-wing populist singers—politically, it’s a very unstable place.

PM: Do you look at Paris differently in the wake of the attacks last November?

LS: It’s a sad and terrible thing. I suspect that the war with certain radical factions of jihadist Islam may last some time yet, and all cities are vulnerable to terrorism and surveillance. But I do have a tendency to think, based on past models, that the current wave of terrorism will probably last less time and do less damage than the economic policies that are currently the norm. All you have to do is think about New York City. After 9/11 people were saying we look at New York City very differently, that the city will never be the same again, and for both good and bad reasons, people were saying money will be gone from New York City and we’ll live the way we used to. That lasted about five minutes. The fact of the matter is 9/11 happened, and it was awful, but really, aside from increased surveillance, TSA checks, and things like that, life thereafter resumed as it had been.

PM: Well, fear and insecurity are such overriding factors in determining the way we look at design in cities now, which maybe wasn’t the way it was before.

LS: In this modern world, people who want to live in non-oppressive circumstances also have to make peace with uncertainty and insecurity. It’s a trade-off. If you want to make sure that no terrorists are going to get into your city center, you may be giving up a lot of other stuff as well. Maybe having a good life and a secure life are not the same thing. A secure life might amount to vegetating, leading a routine existence that just stops when you’re dead, rather than having a rich and multifaceted experience.

PM: If an urban planner or designer or architect were to read your book, what’s the message you’d hope they’d get from it?

LS: There’s a lot of talk about the local and about community, and I’m always hoping for an increased focus on that. Of course, definitions differ, but I don’t think we’re going to foster a community where everything is geared toward profit. If all the shops are owned by large corporations, you might have sympathetic local managers but you won’t have sympathetic policy, because that’s dictated by people in a boardroom far away. There’s not much that planners can do about this right now, but I’m hoping that this will not always be the case. I really hope that this is something that can be reversed.

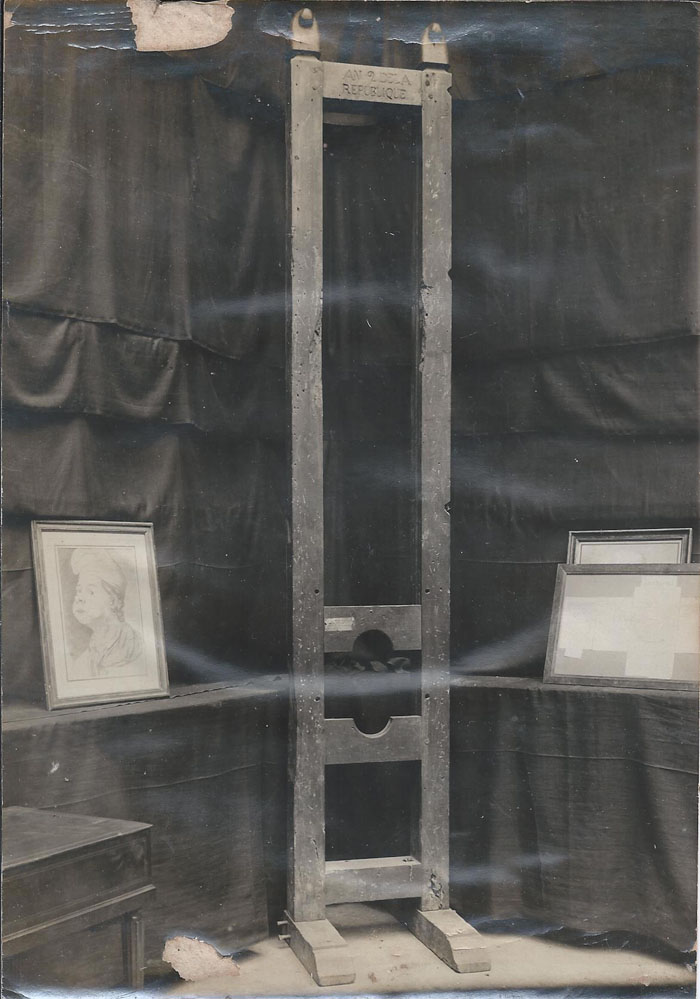

The first victim of the guillotine, in 1792, was Nicolas Jacques Pelletier, who assaulted and robbed people on the street. Shown here is an 18th-century example.

Courtesy Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025