April 20, 2015

Reconsidering the Legacy of Charles Rennie Mackintosh

A new exhibition devoted to Charles Rennie Mackintosh offers an objective appraisal of the architect’s work.

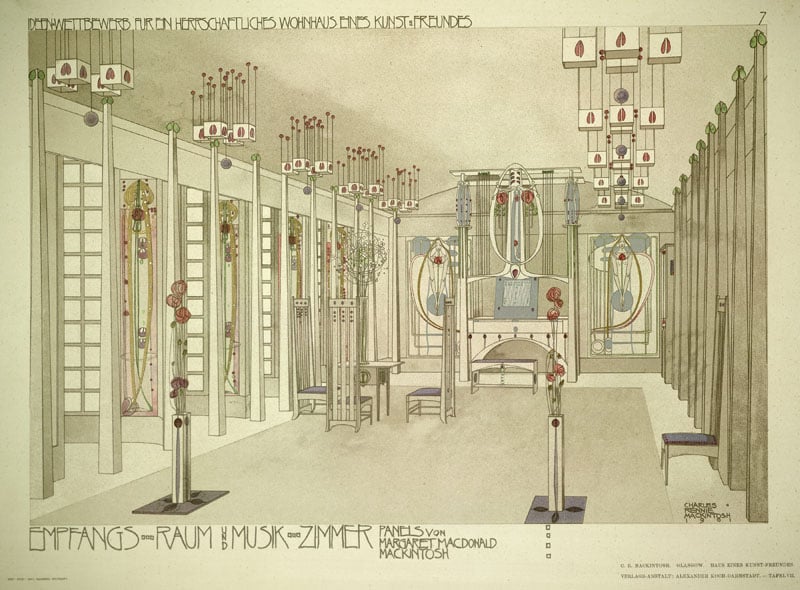

The work of Glasgow architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh is celebrated in an ongoing exhibition at London’s Royal Institute of British Architects. Above: Design for a house for an art lover, 1901

Courtesy RIBA Library

I was indoctrinated into the cult of Charles Rennie Mackintosh at an early age—day one, in fact, of my architectural life. As first-year students at the Mackintosh School of Architecture in Glasgow, Scotland, my as-yet untutored cohort and I were told to head over to the Art School and sketch. Look, the professors said. Draw. Fill page after page till you’ve absorbed the building. Marinate yourself in Mackintosh.

Amongst the paint-spattered stone, timber, and ironwork—all still part of a fully functioning art school rather than a preserved-in-aspic architecture museum—we inhaled the fabulous, mysterious, deep, and rich masterpiece of the building.

The Mac isn’t Mackintosh’s school as, say, Taliesin is Frank Lloyd Wright’s. But the myth of the man works everyone over. Some say you can spot Mac graduates by the first building they design, that there’s an overwrought quality, as if they are trying to pack too much in. If that’s true, then it must come from the intensity of the Art School itself. It’s a building whose eclectic references include Scottish Baronial castles, traditional Japanese architecture, Art Nouveau, and proto-Modernism. But out of this potlatch comes something far more than the sum of its parts, a robust fusion of these disputing elements into a singular entity. Perhaps, it’s that which we ex-Mac-ers are fated to try to reproduce.

The opening of the first substantial Mackintosh show at the Architecture Gallery at London’s Royal Institute of British Architects is long overdue, and not just for those of us within the cult. Mackintosh Architecture aims, it tells us, to contextualize the master’s work in a wider context of his own interests as well as those of the wider world, of turn-of-the-century Glasgow, and his collaborations with his wife, Margaret MacDonald.

Maybe some serious academic rigor can help us look at Mackintosh’s work as distinct from biography.

The show is the crowning of a research project by the Hunterian at the University of Glasgow, which has been fully cataloging Mackintosh’s work over the last four years. This objectivity colors the way the architect and his buildings are presented. It’s an academic show rather than one about undergraduate gut feelings, sensations, or mystery.

Reflecting this, the exhibition is arranged chronologically. First, we have a flavor of the big, successful Glaswegian practice of Honeyman & Keppie, which Mackintosh joined as an apprentice. We see his star rise as he becomes partner. We see his design sensibility grow with (unsuccessful) competitions. We finally see the recognizable Mackintosh emerge in a spectacular drawing of his design for Scotland Street School, where the architecture takes on that signature ancient-modern duality, and around it the sky is inked with the linear intensity of Van Gogh, and trees seem to breed with the organic-graphic turmoil of Egon Schiele. Captured here is not just an architectural drawing, but a statement of Mackintosh’s broad intent of a fusion of art forms—of architecture, art, and graphics all intertwined. It’s this we see culminating in the Glasgow School of Art, shown in the exhibition through an elevational drawing.

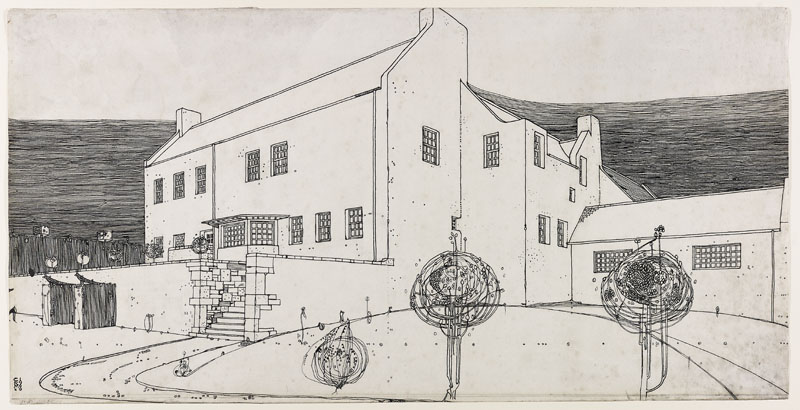

From this apex, the show details what is really a slow decline. The projects get smaller. We see a series of four houses, including the Hill House and Windyhill, shown through restrained models which, as the curators note, have a total contract sum of less than one of the grander villas that Keppie was working on at the time. We see the fragments of his work after his move to London, the partial-studios, the bits of bigger visions, and then his eventual departure for France before the work dried up completely.

Sixty Mackintosh drawings and watercolors, such as this ink rendering of the Windyhill house, are displayed in the show, which runs through May 23, 2015.

Courtesy Glasgow School of Art

Through all of this, the Mackintosh of myth never quite seems to surface. The Mackintosh of the so-called Spook School, the group that comprised Mackintosh, MacDonald, her sister Frances, and Herbert MacNair, whose strange combinations of Celticism, Arts and Crafts, and Japonism produced a hazy, haunted tragedian aesthetic, never quite arrives. Absent is the Mackintosh who fixed iron rings to the wall above a fireplace for the Spook Schoolers to hang onto while drunk. There’s hardly even a flash of his pastel interiors that saw Mackintosh mapping the washed out Spook School aesthetic into three-dimensional form in places like the Willow Tea Rooms. Captions hint at the worlds that were colliding in Mackintosh’s work, but there’s little help to the uninitiated in what these references might be.

But maybe this kind of objectivity is what Mackintosh needs right now. Maybe some serious academic rigor can help us look at his work as distinct from biography, to understand him as a significant and serious architect who helped frame the world from which Modernism would later spring.

When the Art School caught fire last year, there was an outpouring of despair. Though the damage was less than feared, there remained a sense of palpable loss. That’s in part because as a building it not only accommodates its function, but enables the distinct Glaswegian culture—the art, music, fashion, and literature that has flowed through its grand doorway. The building, biography, and Mackintosh myth are all part of its power. But it’s more than this: It’s architecture in its fullest, most inspiring form.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025