February 22, 2021

Comment: Architects Didn’t Invent Redlining, But We Helped Reinforce It—On Two Continents

Activist and architectural designer Wandile Mthiyane examines the twin legacies of American redlining and Apartheid.

As the great architect I.M. Pei put it, “Life is architecture and architecture is the mirror of life.” So, it’s little wonder that I spent my years as an architecture student at a university in Michigan feeling like architecture wasn’t intended for people who look like me. To one professor’s credit we were briefly taught about ancient Egyptian architecture, stretching from the first known architect who designed the pyramid of Saqqara to how great Egyptian ingenuity laid the foundation for the classical architectural language of the ancient Greeks and Romans. But after only 14 pages on Egyptian architecture, we went on to study 576 pages of western typologies with slivers of Islamic architecture worked in. I was learning about and designing buildings that people from my community in Durban, South Africa, might never have the privilege to see, let alone inhabit.

Now, as founder of my own firm, and in light of the recent global protests against police brutality and the continuing work of the Black Lives Matter movement, I feel it’s important for architects to take responsibility for the fact that design has historically been one of the most powerful tools, which perpetuate systemic racism.

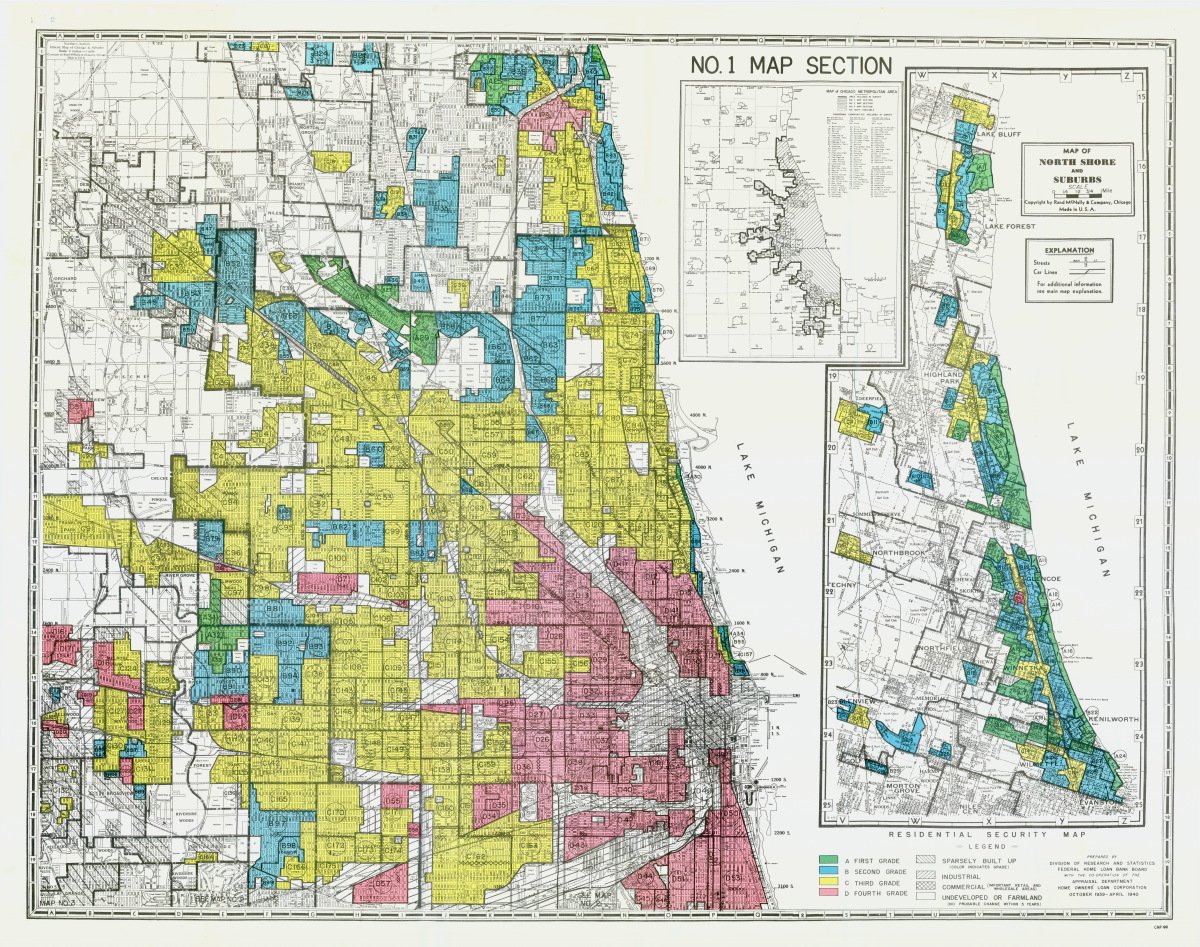

Architecture and planning are at the root of racial bias against people of color in America and around the world. One example: Although discrimination and segregation has always existed in the United States, in 1934, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) put it in writing by instituting the National Housing Act, which created the discriminatory practice called redlining.

Redlining is an unethical mapping practice that literally zones services (financial and otherwise) out of reach for residents of certain areas based on race or ethnicity. It can be seen in the systematic denial of mortgages, insurance, improvement loans, and other financial services based on location, and in that area’s loan-default history. It is a denial of home ownership based on an individual’s ethnicity instead of their actual qualifications and creditworthiness. This resulted in the dividing of neighborhoods along racial lines, leading banks to concentrate lending in certain neighborhoods and not others, based on race. The zoning laws and lending legislation at the time institutionally crippled predominantly African-American neighborhoods, all the while supporting investments in white neighborhoods, and therefore enabling their wealth accumulation.

The effects of redlining persist in neighborhoods such as one where former First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama, grew up on the South Side of Chicago. FHA lending rules (added to the impact of unequal treatment in employment and other aspects of life) helped drive down Black families’ property values. Not every student in the First Lady’s old neighborhood could manage, as she did, to take two buses 12 blocks away to attend Whitney M. Young Magnet school located on Chicago’s west side. Most of the other schools closer to home were under-resourced, which led to high dropout rates. These conditions, which the U.S. government’s policies helped to create were then used by the government to justify their continued use—and, on a local level, to justify a larger police presence in these neighborhoods. Unfortunately, in America this directly relates to the higher numbers of deaths of innocent young Black men and women by the hands of the police.

Thirty-eight years after Michelle Obama’s high school days, not a lot has changed. According to data from the Chicago Police Department, police are 14 times more likely to use force against young Black men than their white counterparts.

In a similar pattern, halfway across the world, apartheid-era architecture in South Africa also segregated communities along racial lines. Apartheid was a system of institutionalized racial segregation that existed in South Africa between 1948 and 1994. It was a system the minority white folks used to effectively oppress, control, and rule over the majority native Black South Africans.

Like American redlining and other government-sanctioned efforts to disenfranchise Black communities, the apartheid-era regime designed working camps known as “townships.” They used a system called the 40-40-40 rule where they built 40-square-meter homes, located 40 kilometers away from economic centers. This forced Black people living in these communities to spend 40 percent of their income commuting to work. The financial drain rendered them incapable of funding development of their own homes. The townships were designed to be devoid of social and economic opportunities, which crippled the Black community’s economy.

Although Apartheid legislations ended over two decades ago, township residents still commute 40 kilometers to work in town centers, limiting them to the same impoverished conditions into which they were forced during Apartheid. The laws may have changed, but the systems remain. Until we change the way we design and build, we’ll not be able to extinguish the evils of systemic racism.

Architecture is never neutral; it either heals or hurts. According to a study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, three out of four U.S. neighborhoods that were redlined on government maps 80 years ago continue to struggle economically. We as architects are not just the designers of glass skyscrapers and infinity pools, but are direct contributors to these injustices. As Winston Churchill best put it, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.”

To make a difference personally, I’ve created a practice where the goal is to liberate and enable people, as much as it is to build. Ubuntu Architecture Summer Abroad Program has created an interesting cross cultural program that focuses on immersing students into a historical, socio-economic, and community-driven design experience. Participants of this program get to work with and under the tutelage of the Umbumbulu community to tackle spatial justice. This program gives students from around the world the opportunity to partner with a local community to co-design culturally-influenced homes for marginalized families in Durban, South Africa. At the end of the program, a local contractor is hired to work with the community to build the homes that students helped co-design.

This initiative begins to peck at the problem by rethinking architectural education and exposing students and young professionals to designing solutions to problems stemming from systemic racism in a place beyond their own contexts. As apartheid architecture was used to segregate and oppress, community-centered design brings people together and enables equitable opportunities for all. We need more efforts that will challenge conventional architectural education and expose students to architecture that represents the world, not just Europe. Architecture that seeks to com up with solutions that will create spatial justice.

As architects, it is important to (and in fact we are trained) take consider the entire environment into which we are designing. Examining existing architecture in the area, accessibility, the path of the sun, the approach to the space, and of course, climate and area become second nature to us very quickly. What we need to also make second nature in our designing and planning is examining the history of a place, the people of a place, and the culture of a place—for everyone.

You may also enjoy “From Housing to Activism, the Next Chicago Architecture Biennial Will Bring Global Issues to Chicago”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025