December 5, 2017

“Resiliency” Has Lost Its Meaning: Why We Need a More Radical Approach

Sometimes it’s better to adapt and retreat before the waters rise again.

Images of the havoc that natural disasters wreak upon the built environment are part of our cultural consciousness. They have been since the birth of photography. Yet the past decade or so has seen a worrisome convergence: the parallel increases in the ubiquity of media technology and the number and severity of devastating storms, which are arguably linked to climate change. Katrina: drowned New Orleans freeways and neighborhoods (the latter re-created in Beyoncé’s 2016 “Formation” music video). Sandy: a darkened Manhattan shot by Iwan Baan. Harvey: Houston’s graybrown floodwaters captured by drone photography. Irma: cell phone footage of a battered port town in the British Virgin Islands.

The degree to which the two are connected—and the importance of that link—was most acute when Hurricane Maria tore through Puerto Rico, cutting out power and destroying telecommunications infrastructure. The Washington Post even attributed the Trump administration’s delayed response in part to not seeing the wreckage.

It’s easy to picture the aftermath of a crisis. But how do we visualize the calm before the storm—resilience in the face of more frequent 100-year floods and storm surges, and rising sea levels? Policies, regulations, and infrastructures that govern a city’s ability to bounce back from disaster are largely invisible—until they fail.

after Hurricane Harvey.Courtesy SC National Guard/Wikipedia

Getting people to adjust to climate realities is challenging. We assume that planning regulations and zoning are in place to protect us. Yet the market often pushes development precariously into potentially hazardous areas, betting on a 100- or 500-year probability.

“No matter how many data points or models you show, no one likes being told not to build somewhere,” says Otis Rolley, a director at 100 Resilient Cities. “It can be difficult and emotional to think about building differently—it is not based on politics or inequity, but about their well-being and the overall wellbeing of the city.”

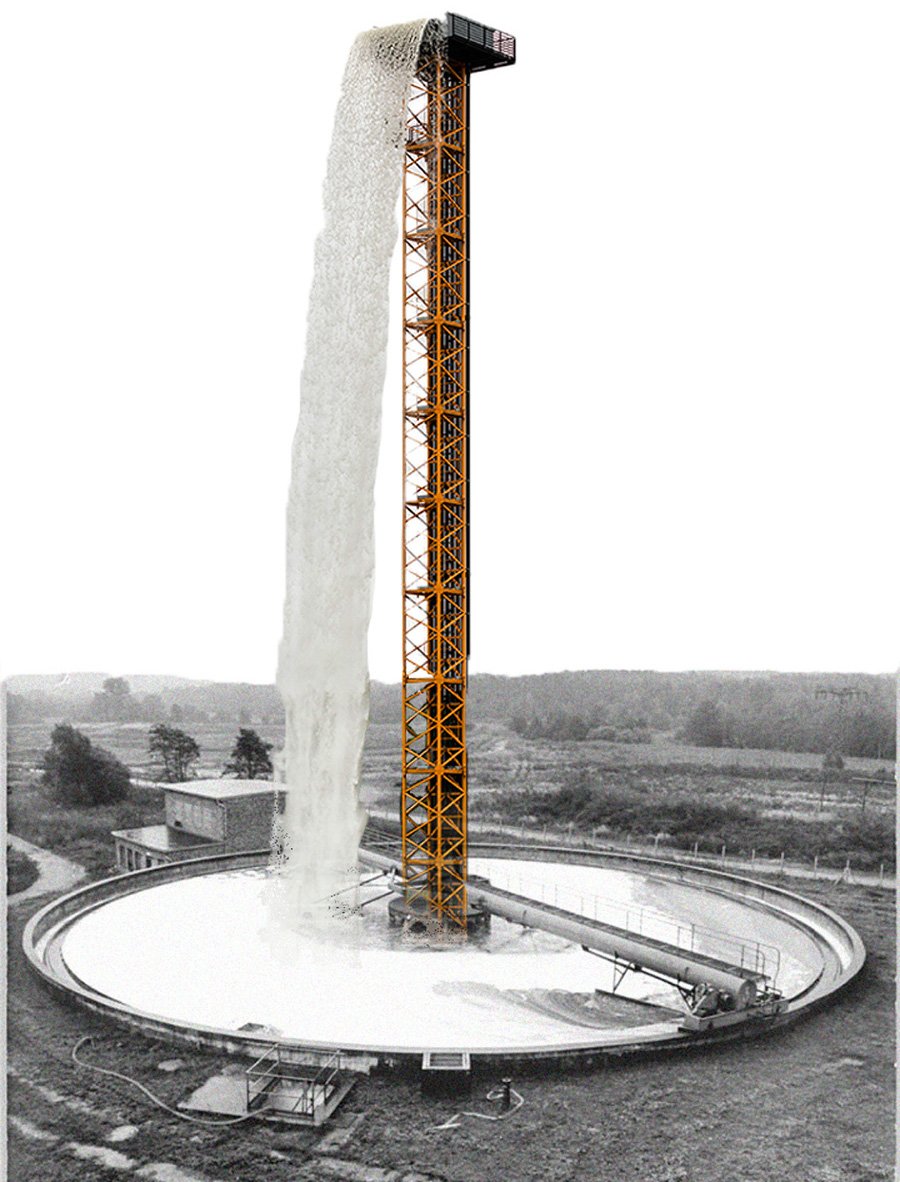

Landscape architect and educator Chris Reed of Stoss thinks that designing infrastructural spectacles could help the public understand what’s at stake. His fall 2016 studio at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) took on a pre-Harvey Houston as a site to investigate how to use landscape to address 21st-century realities of demographics, economics, and climate, among other things. For their studio project, graduate students Louise Roland and Jonah Susskind proposed retrofits of former water treatment pools to create a public pool and a multistory tower with a gushing fountain. If that whimsical fountain were built, it would serve as a daily reminder to the public that water is both a resource and a threat.

For Rolley, the recent storms did bring more public awareness, validating the importance of the work and a comprehensive idea of resilience that is social and economic as well as infrastructural. Yet it’s what he calls the “pre-covery” that remains unseen. “We do the pre-work in understanding the human and physical systems at play and how they can adapt to the shocks and stresses we will face,” he says. “Through data, analysis, and case studies, we advance stories and ideas within the cities we serve. Our goal is to change their approach to these risks before they occur.”

He points to an example in the San Juan, Puerto Rico, neighborhood of Playita, near the Los Corozos Lagoon, where Chief Resilience Officer Alejandra Castrodad-Rodriguez worked with the community, showing residents data models and maps of areas in jeopardy and having conversations about the danger. He estimates that 100 lives were saved, noting that because of those models people understood the risks and evacuated.

As this year’s hurricane season has shown, the optimistic (and perhaps even Modernist) goal of full recovery no matter where we build and what happens is no longer viable. And so there’s a growing tendency among designers and planners to scrap the word resiliency for adaptation, a term that is a bit of a fatalist’s reality check. “Resiliency has gone the way of sustainability—it has lost its meaning,” says Reed. “I subscribe to an ecologist’s definition of resiliency: the ability to adapt to new conditions. A wetland, for instance, changes and evolves over time.”

In Blue Dunes: Climate Change by Design (Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2017), which tracks the development of WXY Architecture and West 8’s post–Hurricane Sandy barrier island proposal for Rebuild by Design, editor Jesse M. Keenan stresses the performative urgency of adaptation, writing “People need to change the way that they produce and consume in response or in preparation to climate change.” Perhaps then, in lieu of arguing for more robust buildings, architects have a responsibility to use their design and representation skills to help a larger public understand what a coastline looks like without buildings, and how a restored ecosystem would better protect inland development.

Architect Jeffrey Huber was a Florida adolescent when he saw his house destroyed by Hurricane Andrew. Now a principal at Brooks + Scarpa, he manages the firm’s South Florida office, where he is a director of planning and urban design. Huber rode out Irma in Fort Lauderdale, which weathered the storm but lost power for a week. Heat-related deaths followed across the state. The situation illustrates the difference between resilience and adaptation: Buildings were resilient and survived, but were ill-suited to what came next. “We are only chasing a symptom,” Huber says angrily. “We aren’t dealing with the inability of our contemporary architecture to allow us to live within the climate.”

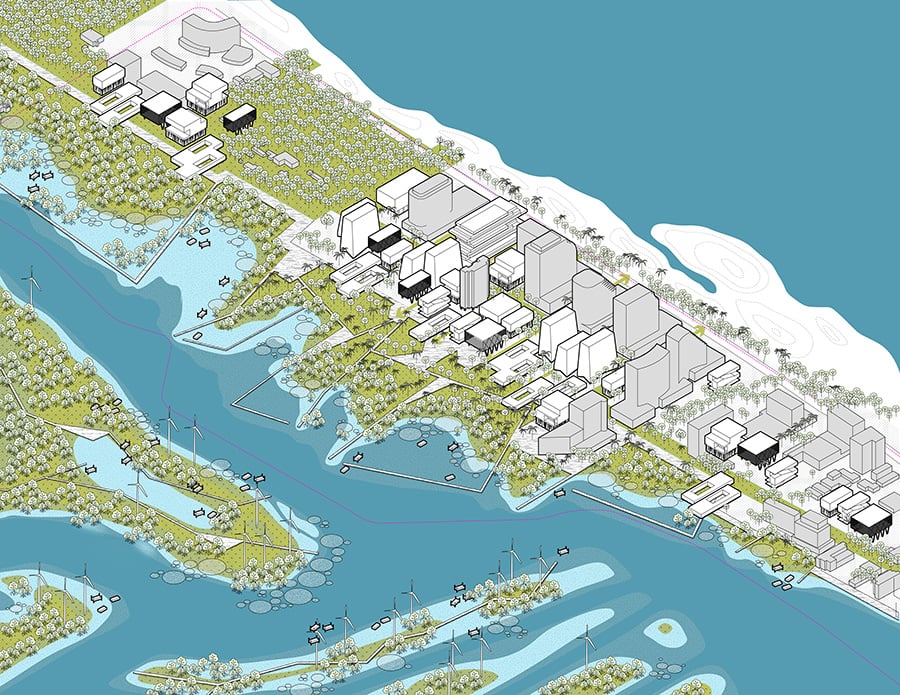

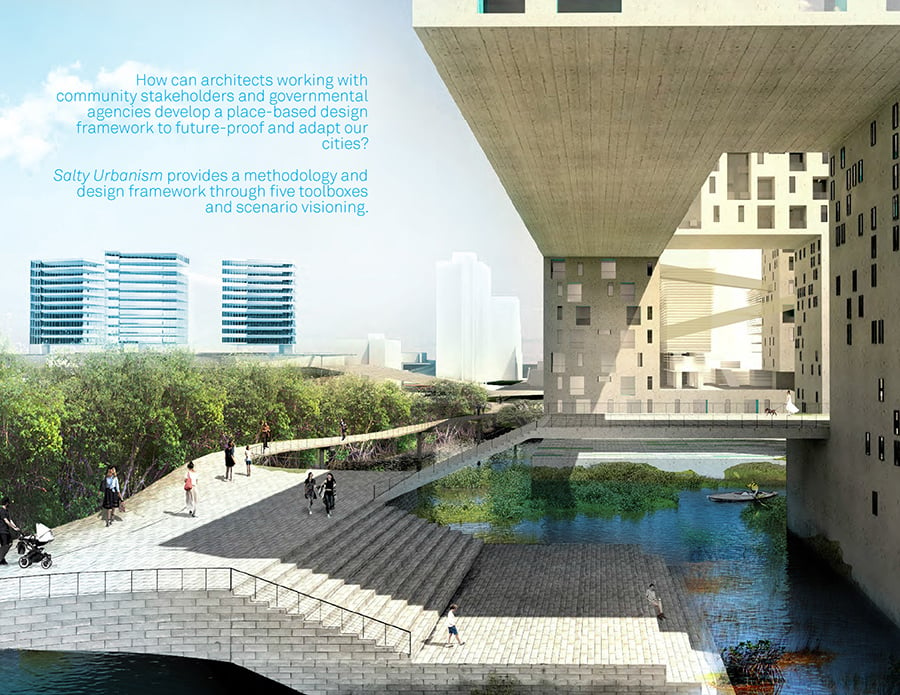

The firm developed a framework for adapting to sea level rise in Fort Lauderdale. Unlike in places like Houston or New Orleans, where low-lying areas affected by flooding are often improvised, underserved communities with few resources for recovery when disaster hits, Florida’s wealthy live precariously on its coast. For the privilege of a sea view, residents will risk the storms and file repeated insurance claims. So Brooks + Scarpa’s proposal for the city includes both urban and architectural adaptation, such as adding salt water–tolerant plants and allowing land to become watery mangrove ecosystems. Home adaptations include building stilts, berms, mounds, or floating structures, and moving structures to higher ground. One of the firm’s scenarios calls for retreating entirely from the coastal edge and letting lowlands rewild into a green infrastructure that can absorb sea level rise over the next century.

Recently in the opinion pages of the Houston Chronicle, Albert Pope, the Gus Sessions Wortham Professor of Architecture at Rice University, similarly called for a tactical retreat from the city’s 100-year floodplain. His op-ed proposed a phased buyout of some 140,000 residential properties that are in harm’s way and reimagining the city’s 150-milelong Bayou Greenways as an expanded floodplain. Just under the surface of his argument lurks the infuriating knowledge that property damage and deaths could have been avoided with better planning.

“Resiliency means you’ve given up on solving the problem,” says Pope, with a scholar’s perspective on the ebbs and flows of growth and shrinkage throughout urban history. “‘Retreat’ is polemical; in the context of economics, technology, or the military, we never retreat. But we have to get real about the forces that we are contending with, and this will require substantially changing our thinking about advancing.” He also warns that the recurring 500-year floods over the past three years will have a long-term impact on the energy sector in Galveston Bay—its ports and refineries, the economic drivers for the city, are just several feet above sea level. If that industry decides to relocate, the city will shrink by default.

Polemical or not, Pope’s proposal is radical in that it offers up one possible solution to visualizing potential climate threats: absence. Reclaimed landscapes across Houston’s sprawl could act as a public reminder that floods are always a danger. Sometimes it’s better not solely to fight for resiliency, but before the waters rise again, to adapt and retreat.

Architecture firm Perkins+Will’s global resilience director Janice Barnes has penned a response to this article, calling it “a polemic and counter to collective experience in practice.” You can read it here.

You may also enjoy “The Bold Plan to Help Save the Mid-Atlantic Coast from Storm Surges.”