December 7, 2020

How Recycling Existing Buildings Could Solve the Urban Housing Crisis

Does the cure for housing insecurity lie in more aggressive reuse of overlooked structures? A growing number of architects and urban activists say yes.

Newly built houses, with their sizable carbon footprints, don’t just contribute to climate change. For many Americans they’re also too expensive—a bitter irony in cities rife with vacant buildings and record evictions.

Given the urgency of both issues, projects that retrofit livable housing into existing low-carbon shells (the initial embodied carbon was spent long ago) might be worth a closer look. We searched for them and came across a handful that promise a cure for housing insecurity and excessive greenhouse gas emissions.

Activist builder Shelley Halstead and architects Peter Birkholz and Katie Swenson stand out as champions of adaptive reuse and renovations as tools for providing more and better housing. Their plans range from makeovers of aging public housing to the careful recycling of one boarded-up single-family property at a time in historically undervalued and devastated neighborhoods.

“Homeownership is how you enter the middle class,” says Halstead. “It’s how you gain wealth and pass on wealth.” That potential for socioeconomic justice is why her efforts are gaining national attention. Her nonprofit Black Women Build-Baltimore (BWBB) trains Black women in carpentry, wiring, and plumbing by directly involving them in the restoration of derelict row houses. It has also occasionally helped prospective homeowners apply for financing.

Halstead brings unique insight and skills to this effort because she has a law degree from the University of Washington in Seattle and she is a member of Carpenters, Local 131. When she relocated to Baltimore in 2015 and saw its vast stretches of blighted housing, she secured a meeting with now-former housing commissioner Michael Braverman and persuaded him not to demolish one condemned block in West Baltimore’s Upton/Druid Heights area, where the vacancy rate is double the city’s average. She then purchased a section of abandoned row houses. It turned out the cost of stabilizing them for rehab was about the same as the city’s price tag for their demolition—roughly $30,000.

Since then, she has handled virtually everything from pulling permits to physical construction, and her clients work side by side with her. Together they lay bathroom floor tile, install radiant heating, and add energy-efficient features such as skylights in halls and between closets to bring daylighting deep into a space and reduce reliance on artificial illumination.

This highly personal design-build model creates a sustainable relationship to homeownership, a strategy that reimagines the outcomes of urban gentrification and the roles of designers and developers in it.

Statistics suggest that the skills BWBB provides can reduce expenses for a group of homeowners who need it the most: According to a 2019 report on racial and gender wealth gaps by researcher Mariko Chang Pyle, single Black women have a median net worth of $100. For single Hispanic women that number is $200. And single Black mothers tend to have $0 in median wealth; single Hispanic mothers have $50. When it comes to financing, women are also more likely to carry higher debt because, as stated in the report, they have lower incomes coupled with the financial burden of parenthood. “Now they’ll have a much better idea of what it takes to fix things and they are less likely to be taken advantage of,” says Halstead.

Many of these abandoned properties are historic, and Halstead takes care in preserving the exteriors while renovating the interiors. Not only does this maintain the architectural fabric of West Baltimore, but it also provides the new homeowners with federal historic preservation tax credits in an area where property taxes are usually high. The Baltimore row houses were initially valued at $6,000 to $11,000, but were recently appraised at $80,000 after renovations were completed.

An hour northwest of Baltimore, financial adviser Reggie Turner has embarked on a similar project using slightly different tools. Appointed by Governor Larry Hogan to the Maryland Commission on African American History and Culture, Turner is leading the rehabilitation of a single property with a provenance: a 180-year-old log cabin, which was until last year run-down and hidden in plain sight in the historically Black Jonathan Street community in Hagerstown. Up until the Fair Housing Act, Jonathan Street was the only place African Americans could live in this city. With help from Habitat for Humanity, Turner hopes to earmark the tiny structure not as a museum but as a permanent home for a Black veteran. Two hundred square feet are being added to increase its living space. “Preserving our story helps preserve us,” says Turner. “This is our way of taking the oldest property in the community and staking a claim.”

Meanwhile, on the West Coast, Birkholz, a principal for Page & Turnbull in San Francisco, is converting the Capitol Park Hotel in Sacramento, California. The massive renovation will transform it from a makeshift temporary shelter into high-quality permanent, supportive studios—Birkholz’s first such project in a career that spans 30 years.

While some developers convert single-room-occupancy hotels into chic micro-units, Mercy Housing, which purchased Capitol Park, is leasing it to the Sacramento Housing and Redevelopment Agency and preserving existing units for the city’s disadvantaged. The project is budgeted at $32 million with $2 million going toward its design.

Birkholz felt this was an ideal time to use his expertise in historic preservation to enhance the lives of people who already live nearby. “Next to the freeway there are homeless people sleeping in tents, and Caltrans is coming and sweeping them up on a weekly basis,” he says. “There’s just such a need for this kind of housing.” City officials want the 107-year-old hotel converted into a full-service shelter with intervention services on the ground floor.

“Given the condition of the building, everything will need to be replaced,” Birkholz explains, adding that his team will use the opportunity to install state-of-the-art updates and materials that meet California LEED and Title 24 environmental standards. Common areas and single-room units will be redesigned, including adding fully functioning individual kitchens. Fire safety and indoor air quality are also being addressed: “Given the recent wildfires, we’re putting in a complete heating and cooling system, which will provide filtered air.”

Because several of the tenants are disabled veterans, Birkholz plans to design some units as adaptable or fully accessible units. “I find it gratifying that we’re able to mix what we do best, which is working on existing and historic buildings, and try and meet this need,” he says. “It’s one small step toward helping solve a larger problem.”

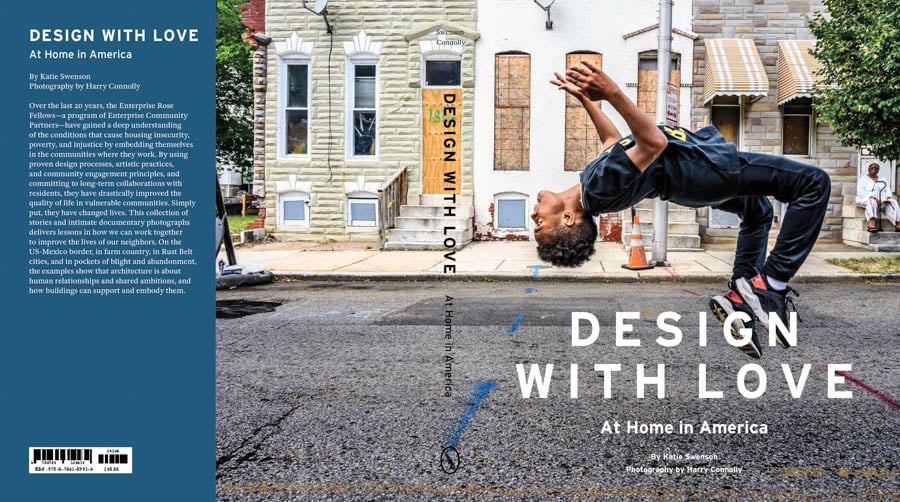

For Katie Swenson, a senior principal for MASS Design Group and author of Design with Love: At Home in America (Schiffer, 2020), working in this space where green reuse dovetails with social justice is familiar territory. Swenson is a national leader in sustainable design for low-income communities, a longtime advocate of high-quality housing for all.

As the former director of the Enterprise Community Partners Rose Architectural Fellowship, Swenson has taught architects the methodology behind community-first design, and reusing existing properties is an important part of the toolkit. “The most sustainable building is going to be one that already exists,” Swenson says, referring to the carbon debt associated with demolishing a building to erect a new one.

One special design question she routinely asks is “How do we choreograph the way a building works from public to semipublic to private spaces?” In the throes of the coronavirus pandemic this is a very timely question with regard to housing vulnerable populations. Because MASS got its start designing hospitals to prevent the spread of infection, Swenson says, the firm has also been applying this methodology to housing design.

For example, the JJ Carroll Apartments, a 64-unit federal public housing development, are being reimagined using some of the principles of infection control. For their construction, on the site of an existing housing project, Swenson researched senior housing and the ways the elderly are more vulnerable to isolation, depression, and COVID-19.

The design of the multifamily project will increase density on the site to maximize units’ affordability but cluster neighbors into small groups of five to eight units. “We designed micro-neighborhoods that allow tenants to be neighborly but also socially distant,” says Swenson. The architects also plan to get rid of long corridors, which can be vectors for disease spread. Neighbors can gather instead in a planned Zen garden and an intergenerational playground that will feature the usual swing sets and slides as well as areas where older adults can sit and relax.

There is a key to mastering this kind of mindful design, Swenson says: Architects need to be supportive. Their approach to projects shouldn’t be to “design for” the community, but to listen and amplify the voices of those who are already there.

You may also enjoy “Joseph Kunkel is Fast-Tracking Quality Housing for Indigenous People“

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Register here for Metropolis’s Think Tank Thursdays and hear what leading firms across North America are thinking and working on today

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025