August 31, 2021

A New Tower, Underway in Boston’s Seaport District Aims to Right Aesthetic and Environmental Wrongs

How do you protect the district while not cutting people off from the water’s edge?

Zachary Chrisco, Sasaki principal and civil engineer

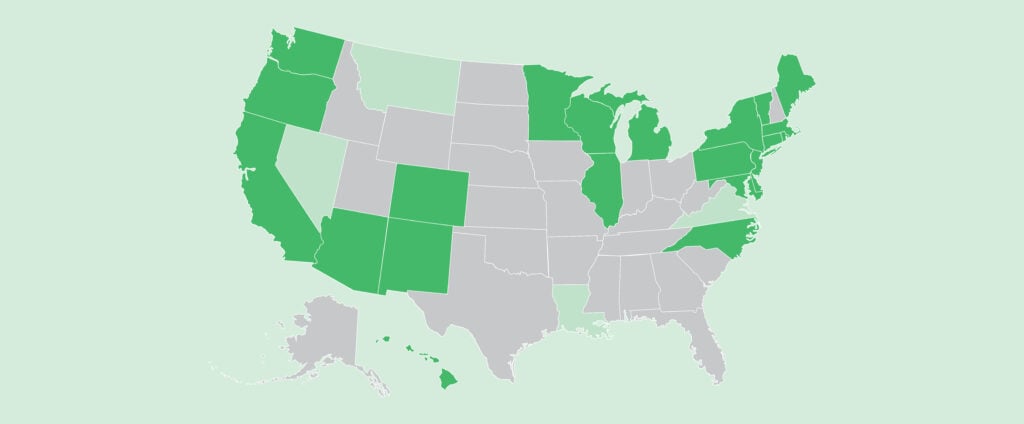

Enter Sasaki, the multidisciplinary architecture, engineering, and landscape firm based in Watertown, Massachusetts (but moving to new digs in downtown Boston soon). The firm has designed Ten World Trade Center, with swooping geometric forms that eschew the orthogonal orthodoxy of its neighbors. Furthermore, the firm has been a key consultant on studies focusing on climate change resiliency in the Seaport District and throughout the city, chiefly as part of a team behind Climate Ready Boston, published in 2016 by former Mayor Martin J. Walsh’s administration.

Ten World Trade Center was designed both for architectural novelty and resilience. “Massport, which controls the site, and Boston Global Investors, the developers, wanted something different,” said Victor Vizgaitis, Sasaki principal and the firm’s chair of architecture and interior design. “Design was part of the early discussions.” As a means of climate resiliency, “Both the lobby and infrastructure that you usually see at ground level are raised,” Vizgaitis continued. “But the lower portion of the building, defined by structural arches, is a civic space open to all 24/7.”

The architect described the building, which will be a multi-tenant office, as being “like the section of a cone, with curtain walls that curve and flair outward. It’s a structural engineer’s dream because it’s so different.” Boston-based Thornton Tomasetti were the structural engineers. Construction of the building is expected to start in the fall.

“How do you protect the district while not cutting people off from the water’s edge?” asked Zachary Chrisco, another Sasaki principal and civil engineer who was involved in preparing Climate Ready Boston. “It’s complicated. So many entities, public and private. But there’s the common goal of trying to protect the neighborhood.”

Richard McGuinness, deputy director for climate change and environmental planning at the Boston Planning and Development Agency, put rising waters in a historical perspective. “People need to realize that Boston has more than 5,000 acres of created land,” he explained that the city grew by filling in parts of Boston harbor with earth, rubble, and occasionally, trash, creating more real estate on which to build. All that land, he said, is especially vulnerable.

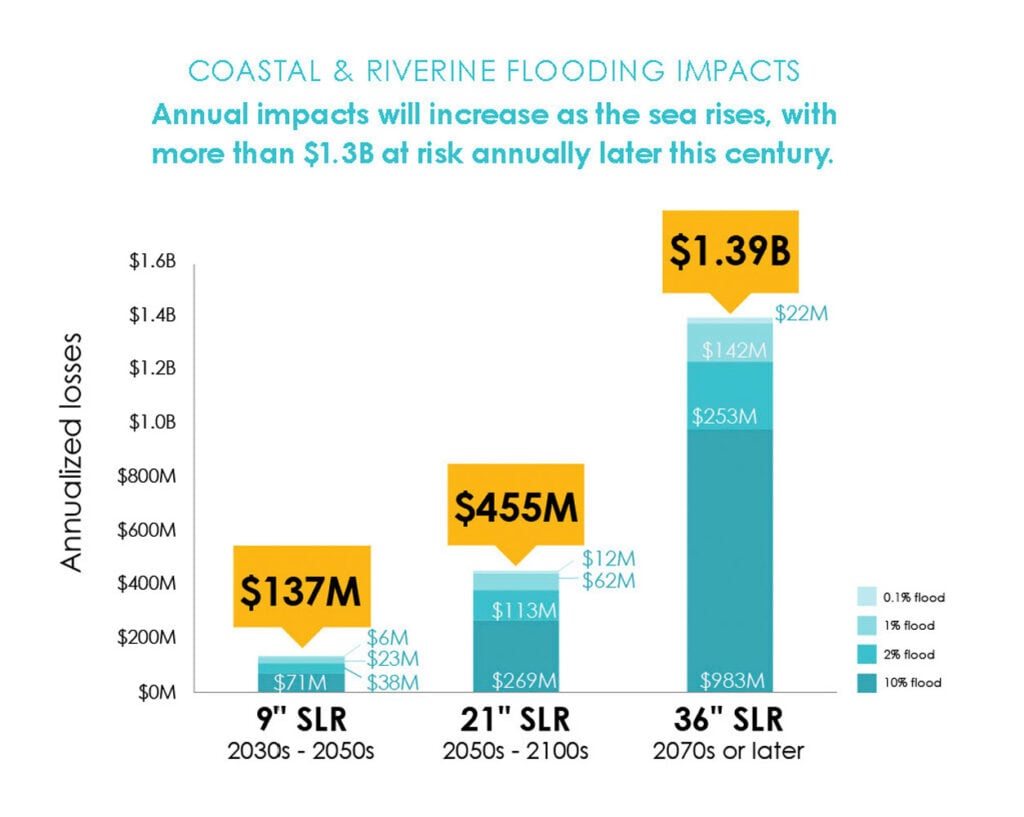

“When developers apply for approval, we make sure their project is ready for sea level rise,” McGuinness continued. “For 2070, it’s actually predicted to be 36 inches of sea rise and 4 inches of land sinking. That’s the way it is with created land.”

One architectural element that is going to be used extensively in the Seaport District is the berm, which McGuinness described as a cross between a seawall and a levee. Architects will be able to use their creativity to design these however they want, he explained. The key is that they be high enough and strong enough to withstand not just sea rise but also Nor’easters, which are the region’s most frequent storms. “A strong Nor’easter slams water into Boston Harbor,” he said, “and we’ve got to protect these buildings.”

For his part, Sasaki’s Vizgaitis is focused not just on resiliency and sea rise but how Ten World Trade Center works architecturally and in relation to the urban fabric around it: “The idea of the public realm was paramount. This building must act as a gateway to the Seaport District.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Projects

Taisugar Circular Village is a Model Case Study for Circular Economies

The Taiwanese project by Bio-architecture Formosana claims to be the first residential village in the country to be integrated within a circular economy.

Viewpoints

3 Sustainability News Updates for Q1 2025

Local laws, easy-to-access tools, and global initiatives keep the momentum on green building going.

Viewpoints

Women Architects Struggled to Find a Home Within Modernism

American women offered a counterpoint to the boys club of the International Style, a new book says.