August 28, 2014

Snøhetta Rethinks the Future of Times Square

The Norwegian architects on how they’re transforming public spaces into “platforms for living”

Renderings courtesy Snøhetta & MIR

Designing public space is a tricky thing. It is often a contradiction in terms, since the best ones tend to feel organic and, in some mysterious way, undesigned, even inevitable. When public space is reimagined, the danger is often the overweening tendency of architects and planners to want to control it—to create Master Plans rather than Passion Plans. But as we like to say at Snøhetta: The best-made plans never get laid. People will appropriate space in unforeseen and wholly unpredictable ways. We shouldn’t fight this human tendency; we should embrace it.

Good planning has to think as much about the spaces in between objects as the objects themselves, as much about the unknown as the known. The idea is to design an appealing platform, a series of nonprescriptive cues that encourage people to occupy space and then invent their own uses for it. If you provide them a degree of choice, they will take ownership of that place. If you bend them to a particular set of rules they will either subvert those rules, or vote with their feet and hang out elsewhere.

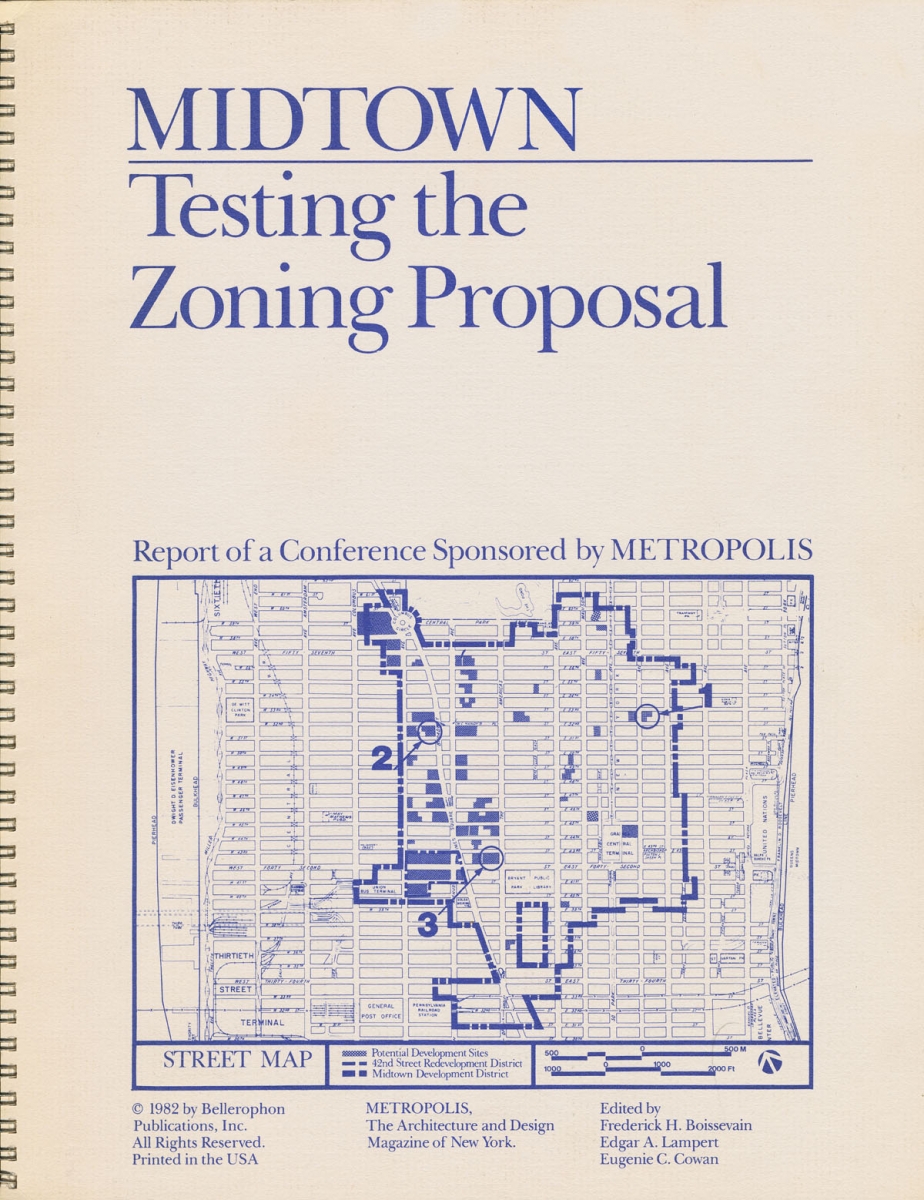

Courtesy Metropolis Archive

1981

Public and private sector experts at this first interactive Metropolis conference analyzed proposed zoning changes for Midtown Manhattan. Many theater district solutions became realities. Participants still recall this landmark event.

2015

Snøhetta’s redesign of the public spaces in Times Square includes granite benches; precast concrete pavers (below), inlaid with stainless-steel pucks that reflect the flashing LEDs of the square; and an open, deliberately nonprescriptive ground plane.

Our work for the city in Times Square, to redesign the “bow tie”—the plazas extending from 42nd and 47th Streets between Broadway and Seventh Avenue—uses many of these same principles, but at the same time realizes that the “Crossroads of the World” is a special case. Times Square is both loved and reviled by New Yorkers. It epitomizes the old Yogi Berra-ism: “Nobody goes there anymore, it’s too crowded.” It’s also unsafe. So, how do you manage the hordes of tourists who flock to Times Square while still creating an appealing streetscape that might attract New Yorkers? By removing the existing curbs and the redundant streetscape infrastructure, a clear, simple ground plane is created.

This new surface, made of precast concrete pavers in dark street-like colors, and inlaid with stainless-steel pucks that reflect the LED signs above, forms an anchor for the space that allows the excitement of Times Square to shine more brightly above. People receive subtle design cues from the patterning and grading of the surface informing how they might move, where they might stop, where events might take place. Using robust granite benches to break down the scale into a human dimension will encourage people to congregate in different ways, and help orient and direct visitors along Broadway. In an effort to relieve overcrowding, we’ll try to lure tourists into gathering spaces, thereby freeing up sidewalk space for the 300,000 New Yorkers who work in the neighborhood. But what underscores this effort is the overriding goal to create a generous and comfortable platform for pedestrian activities.

Courtesy Snøhetta

These types of spaces are likely to become increasingly important as the world continues to urbanize. We worked in the capital city of Conakry, in Guinea. Officially, it has about two million residents and no central electrical grid. So, at night, when the sun goes down, there are no lights in the houses. People drag their dining tables out in the street, share common candles, and the city becomes a giant living room. This is “public space” at a scale most of us are completely unaccustomed to. It’s of course totally ad hoc and improvised, and holds all sorts of lessons for us in the West about community. We all want our city to belong to us in some intimate way. We all want to cross the same thresholds that the people of Guinea cross when the sun goes down in the evening. How do you live with your neighbors? How do you create a shared platform for living?