October 11, 2021

An Exhibition Allows Visitors to Experience Long-Demolished Works by Wright and Sullivan

The Garrick occupies most of the exhibit space, which is spread across two floors. On one, the building is alive, playing host to Jane Addams and Eugene Debs in the 1910s, and Billie Holliday and Duke Ellington in the 1940s. Its luxurious aura is brought back to life with recreated ceiling stencils and ornamental friezes alongside several original plaster figures. Its soaring exterior and dramatic interior are further reanimated through a stirring, if occasionally uncanny, digital recreation video that presents the structure with an (imaginary) fullness that its fragmented physical artifacts can only gesture at.

Upstairs, haunting images of the building’s demolition in 1961 reveal the great cultural cost paid. Its destruction inspired renowned photographer Richard Nickel to preserve as much as possible; he also hired young architect John Vinci, who later refurbished Wright’s Oak Park studio and recreated Alder and Sullivan’s Stock Exchange Trading Room at the Art Institute, to help in the work. One image of the theater’s soaring roof, stripped of ornament and reduced to twisted fragments of its steel frame, is a stirring reminder of why thoughtful preservation remains vital today.

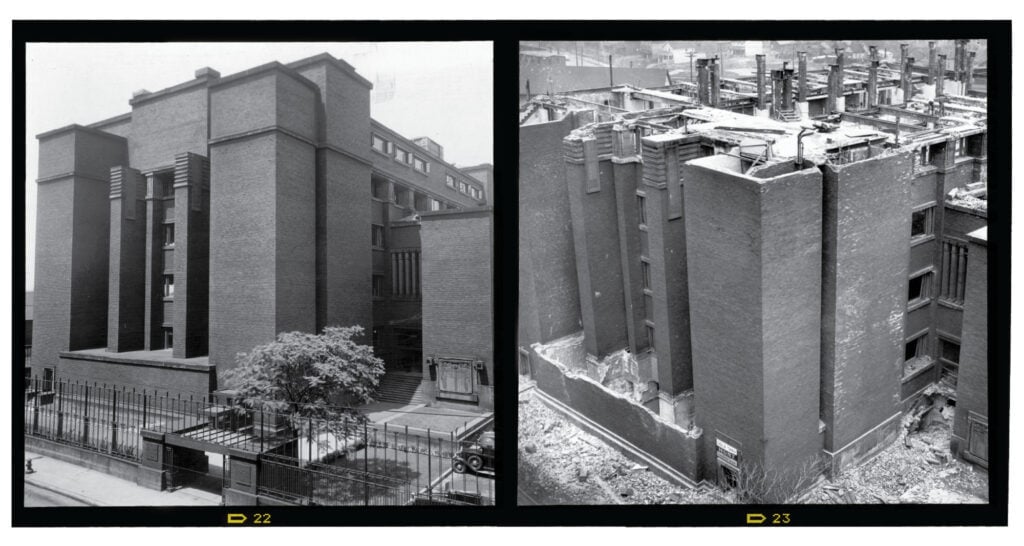

Wright’s Larkin Building, built in Buffalo to house one of the country’s largest mail-order companies, is no less impressive, even if it occupies less gallery space. Remaining examples of Wright’s office furniture compliment a dramatic, 20-foot-tall image of the building’s roomy, light-filled interior, placing the Larkin at the forefront of the open office movement. The exhibit also shows a 1947 newspaper ad, showing the building “Available at a fraction of its cost,” still not enough to spare its demolition in 1950.

While neither building gets much attention compared to others from Sullivan and Wright, each were vital early commissions that solidified their reputations and ensured later masterworks. It’s a crime that both buildings are not with us today; still, “Romanticism to Ruin” helps us appreciate them anew. “Put the city up; tear the city down,” Carl Sandburg warned in his 1914 poem The Windy City, quoted in the exhibit. The next line, “Put it up again; let us find a city,” pushes us to find fresh meaning from these absent edifices, rekindling something meaningful we’ve lost along the way.

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Profiles

Zoha Tasneem Centers Empathy and Ecology

The Parsons MFA interior design graduate has created an “amphibian interior” that responds to rising sea levels and their impacts on coastal communities.

Viewpoints

How Can We Design Buildings to Heal, Not Harm?

Jason McLennan—regenerative design pioneer and chief sustainability officer at Perkins&Will—on creating buildings that restore, replenish, and revive the natural world.

Products

Behind the Fine Art and Science of Glazing

Architects today are thinking beyond the curtain wall, using glass to deliver high energy performance and better comfort in a variety of buildings.