May 10, 2016

The A to Z of Issey Miyake

A lexicon and guide to the designer’s groundbreaking portfolio, collaborators, and innovative thinking

Japanese designer Issey Miyake passed away on August 5, 2022, at age 84. This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of Metropolis.

On March 16, Miyake Issey Exhibition: The Work of Issey Miyake, devoted to the last 46 years of the designer’s career, debuted at Tokyo’s National Art Center and will run through June 13. To coincide with the show, Taschen published a massive tome simply titled Issey Miyake that is certain to become the definitive work on him. As if that’s not enough, this month, Miyake will also be included in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Manus x Machina: Fashion in an Age of Technology, showcasing his merging of traditional practices with advanced techniques. It is clearly time to reflect on the work of this Hiroshima-born “original maker” who remains one of the most important creative visionaries in the world.

Since founding his studio in 1970, Miyake has created textiles, clothing, accessories and interior lines that are rooted in innovation, beauty, and a strong tradition of making. From his technologically innovative heat-pressed pleats to his garments made from single pieces of cloth, the designer has been pushing the boundaries of what fabric can be and how it relates to the body. At a time when fashion has become mere styling, Miyake has instead produced garments—from the Pleats Please to A-P OC collections—that flatter every body shape. “My clothes become part of someone, part of them physically,” Miyake once said. “Maybe I make tools. People buy the clothes and they become tools for the wearer’s creativity.”

At 78, Miyake is more relevant than ever, influencing a new generation of designers such as Proenza Schouler, Jonathan Anderson, and Naoki Takizawa. At the exhibition opening in Tokyo, Miyake was presented with France’s premier award, the rank of the Commander of the Legion of Honor—a fitting tribute to a revolutionary designer who continues to look to the challenges of making the world a more beautiful and sustainable place. Here, we’ve created our own tribute of sorts—a lexicon and guide to the designer’s groundbreaking work, collaborators, and innovative thinking—providing an opportunity to experience his joy of creation and hinting at greater possibilities in the future.

A for A-POC

B for Body

C for Collaboration

D for Dance

E for East Meets West

F for Folding

G for Graphic Design

H for Hiroshima

I for Irving Penn

J for Joy

K for Kuramata

L for Light and Shadow

M for Material

N for Noguchi

O for Olympics

P for Pleats

Q for Quotidian

R for Reality Lab.

S for Skin

T for Tattoo

U for UFO

V for Volume

W for Water

X for XXIc

Y for Yokoo

Z for Zoomorphic

A for A-POC

A-POC, which stands for A Piece of Cloth, is based on an idea that Issey Miyake came up with of creating clothes made out of single pieces of cloth that would envelop the body. It all started with the 1997 Just Before collection, which is based on an industrial knitting machine programmed by a computer to produce a series of tube-knit dresses or shirts that are continuously connected. Each piece can be cut out in a variety of ways, allowing users to shape the clothes according to their whim. “I have endeavored to experiment to make fundamental changes to the system of making clothes,” Miyake once said. “Think: A thread goes into a machine that in turn generates complete clothing using the latest computer technology and eliminates the usual needs for cutting and sewing the fabric.” The process he developed for making these garments not only reduced the need for resources and labor, but is also a means to recycle thread. —Paul Makovsky

B for Body

From 1980 to 1985, Miyake created Body Series, a collection of sculptural clothing that covers the torso and is made of hard materials that had never been used for clothing before like fiber-reinforced plastic, synthetic resins, rattan, and wire. Plastic Body, from the autumn-winter 1980 collection, for example, was made from plastic; and Rattan Body (spring-summer 1982, shown here) used rattan and bamboo and was featured on the cover of Artforum. “These sculptural clothes—clothing for militant women, we might say—were created out of both Miyake’s unrestrained and ever-searching mind as well as his efforts in support of new technologies and traditional skills,” writes Yayoi Motohashi, curator of Miyake Issey Exhibition: The Work of Issey Miyake at the National Art Centre Tokyo. —P.M.

Miyake’s career has been marked by a number of partnerships with creative legends in their own right— like Irving Penn, Ikko Tanaka, Shiro Kuramata, and Ron Arad—and more recently with design brands Artemide and Iittala. “Designing clothes isn’t solitary work, it requires associations with many people,” Miyake was quoted as saying in the book Irving Penn Regards the Work of Issey Miyake (Bulfinch Press, 1999). “I want people to know everything is the result of teamwork—like making a movie.”

From 1996 to 1998, as part of the Guest Artist Series, Miyake invited four collaborators to use his Pleats Please collection as a canvas for their work—Yasumasa Morimura (left), Nobuyoshi Araki (opposite, top left), Cai Guo-Qiang (opposite, top right), and Tim Hawkinson (opposite, bottom row)— with results that were both provocative and humorous.

However, Miyake makes clear that his ultimate collaborators are the people who wear his clothing: “I love to see people make [the clothes] no longer mine, but their own. When I see the clothing worn, our communication is complete.” —Avinash Rajagopal

After a French friend of Miyake’s saw some of the first pleats that the designer had created and suggested that they were perfect for dance, Miyake had William Forsythe’s Frankfurt Ballet Company test them out. Miyake designed costumes with polyester tricot pleats for the performance of The Loss of Small Detail in 1991. The pleats in knit fabric not only accommodated the intensity of the dancers’ movements, but their bodies were also transformed by it. Watching them dancing in the costumes, Miyake realized that if dancers with such a wide range of body types and heights had so much fun wearing them, ordinary people might too. Later research and development led to the launch, in 1993, of Pleats Please. Over the years, Miyake continued to collaborate with other dancers and choreographers such as Trisha Brown and Danny Ezralow. —P.M.

Miyake sees himself as part of a generation in limbo. “We were the first really raised with Hollywood movies and Hershey bars, the first who had to look in another direction for a new identity,” he wrote. “We dreamed between two worlds.” He is very proud to be Japanese, however. “I was born in Japan, I love Japanese food, and I understand Japanese artists,” he once said. “But there are some other things I understand also. And I am not here as a spokesman to the West, to explain what Japanese is.” Miyake also explained that while working in Paris during the 1960s, he discovered that what was supposed to be a disadvantage—his lack of Western heritage—could really be an advantage. “It freed me,” he said. “I had nowhere else to go but forward.” He used the title of his book Issey Miyake: East Meets West (Heibonsha Ltd., 1978) to make a statement that “the two polarities had become one” whereby “future generations will mingle even more.” —P.M.

“It was a scarf that triggered it all,” remembers Kazuko Koike, creative director at Miyake Design Studio (MDS). Textile director Makiko Minagawa was undertaking some material explorations, and she took a piece of polyester and folded it. “By chance,” Koike says, “Issey happened to notice.” That was the birth of Pleats Please Issey Miyake and a career-long development of folding techniques. Folding, of course, was an art form expanded and perfected in Japanese culture—at MDS, this intersected with cutting-edge techniques and new materials, such as tissues transformed by folding and heating, as well as recycled polyester. In recent years, pattern engineer Sachiko Yamamoto has been working with young researchers, in addition to Professor Jun Mitani from the University of Tsukuba, to apply mathematical research and software development to the art of folding. —A.R.

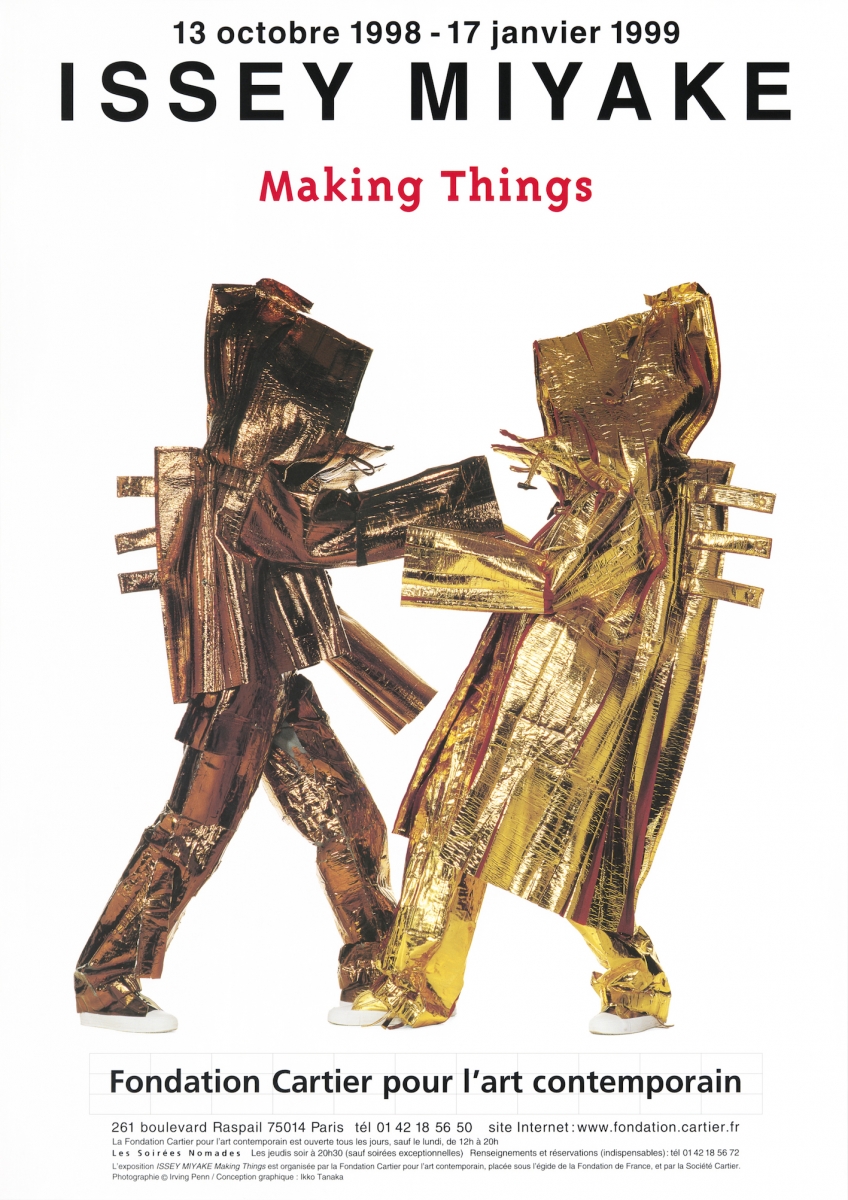

One of Miyake’s most noted graphic design collaborators was the Japanese designer and art director Ikko Tanaka—known outside Japan for his famous logotypes, including the one for Muji. The two met in the 1960s and shared an enduring friendship until Tanaka’s death in 2002. Among the 640 books that Tanaka worked on was the groundbreaking volume Issey Miyake: East Meets West (Heibonsha Limited, 1978); the art director also created all the advertising for Pleats Please between 1994 and 1997. In 2016, Miyake paid tribute to his friend with the series Ikko Tanaka Issey Miyake, converting two of Tanaka’s most famous works into motifs—the 1981 poster Nihon Buyo, created for a performance of Japanese dance at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the 1995 poster The 200th Anniversary of Sharaku. Transferred onto coats and put through a pleating machine (above), Tanaka’s masterpieces—two-dimensional both in their original format and in their approach to form—acquire volume and dynamism when worn. —A.R.

These comments are excerpted from the article “Issey Miyake Talks About A-Bomb,” which appeared in the December 6, 2015, edition of the Japanese newspaper The Yomiuri Shimbun.

I had decided not to talk about the atomic bomb. I didn’t want to be called a “pikadon designer.” [Pikadon is a Japanese word that describes the intense flash of light as the bomb exploded and the strong shock wave immediately afterward.] I thought it was pathetic to use the atomic bombing as an excuse. . . However, I thought the world might change a little if a person like me, who has symptoms of radiation exposure, tells my story.

I was a first-grade primary school student when the atomic bomb was dropped 70 years ago on Hiroshima on August 6. I heard the boom all of a sudden when I entered a classroom after a morning assembly. A broken piece of window glass got stuck into my head. I was frightened.

I was living in the town of Fuchu, adjacent to Hiroshima. My house, where my mother was, was 2.3 kilometers away from the epicenter of the bomb blast.

I told the people at the home to which I had been evacuated, “I want to go home,” and they gave me lots of hard, dry biscuits. I headed home alone to search for my mother.

People were burned, lying on top of each other, and others gathered at a stream for water. I found my mother, who was burned over half her body, the following day. I asked where she was receiving treatment and went to see her.

As soon as my mother saw me, she said. “You’re the oldest son, so go to the countryside, where it’s safe.” She said that so I’d survive, I guess. My mother was a strong-minded, steady person. She was loved by her neighbors and relatives.

I developed periostitis due to radiation exposure when I was a fourth-grader at primary school. Some people died of this disease, but I was saved by penicillin. My mother nursed me while I was fighting the disease and died soon after my condition improved.

I liked painting since I was a primary school student, and Susumu Hasegawa, my homeroom teacher in the fifth and sixth grades, taught me painting. I couldn’t afford to buy brushes, so I used my fingers to paint. I even submitted my work to a newspaper. Hasegawa continued to support me after I became a designer. I was interested in basketball in middle school, but I started having trouble with my leg. . .

There are people who experienced tragedy in Hiroshima and people who suffered in Fukushima due to the nuclear accident. I wonder how things will change in the world from now on. [Actress] Sayuri Yoshinaga continues poetry readings about the atomic bombing, and that is a truly great thing. I wrote a letter to President Obama, asking him to visit Hiroshima in 2009: I couldn’t stop myself. Those who speak up are great regardless of whether they are famous. In the present age, each person has to ask themselves again how to live.

As a student in the 1960s, Miyake admired Irving Penn’s photographic work in Vogue. “When I saw Penn’s photographs, it was clear that they went much further,” Miyake said in the 1999 book about their collaboration. “I realize that he is the most remarkable photographer who looks at clothes with a completely different eye. And I wanted to undertake something with him.” They began working together in 1986 and had produced almost 250 photos by 1999.

Penn was given complete artistic freedom, leaving Miyake’s trusted colleagues Midori Kitamura and Jun Kanai to coordinate sessions in New York along with Tyen, who did the makeup, and John Sahag, who did the hair. “Twice a year, after we had returned to Tokyo, Issey Miyake and I would select clothing for me to take to New York to be photographed by Mr. Penn,” says Kitamura. “For me, the photo sittings were always filled with surprises.”

Though familiar with Miyake’s clothes, she would see them transformed by Penn’s lens. “It became an entirely new world for me. Miyake would then inevitably be surprised and moved by the photos I brought back to him.” Miyake concurs with Kitamura: “I was looking for one person who could look at my clothing, hear my voice, and answer me back through his own creation. Through his eyes, Penn-san reinterprets the clothes, gives them new breath, and presents them to me from a new vantage point. He shows me what I do.” Photos by Penn allowed Miyake—who never attended the photo shoots—to look again at his designs as if they were completely new. —P.M.

Many critics around the world have independently reached the conclusion that Issey Miyake is not a fashion designer. “He calls his activity ‘making things,’” clarifies curator Angelo Flaccavento, positioning Miyake above the tug-of-war between practicality and style that characterizes fashion design. Instead, what distinguishes his work is an incurable optimism (expressed above in a photo shoot for his spring-summer 1976 collection), and the designer has adopted the mind-set itself as a way to describe his vocation—which is especially convenient because one of the Japanese words for clothing also has positive connotations. “We have three words: yofuku, which means Western clothing; wafuku, which means Japanese clothing; and fuku, which means clothing,” Miyake told Time magazine in 1986. “[Fuku] can also mean good fortune, a kind of happiness. People ask me what I do. I don’t say yofuku or wafuku. I say I make happiness.” —A.R.

During the 1970s, Miyake identified Kuramata as an important new talent and asked him to design the Issey Miyake shop in the From–1st Building in Tokyo in 1976. Kuramata proposed laying garments out on flat surfaces and designed a table made of aluminum honeycomb sheet with a timber surface that cantilevered out of the wall and appeared to be floating with no visible means of support. His shop for Bergdorf Goodman used terrazzo extensively, while the Paris shop used walls draped with fabric. Over a decade and a half, Kuramata designed more than 100 interiors for Miyake.

Long after Kuramata’s death, Miyake maintained the two shops he designed in the Aoyama neighborhood as a silent tribute. “When we began working in early 1960s, Japan was at the height of its post-WWII economic recovery,” Miyake said in a statement on the occasion of the 2011 exhibition Shiro Kuramata Ettore Sottsass. “Kuramata was a heroic presence to me, even within a group comprised of so many formidable talents. His use of materials, for example: No matter what it was, he transformed it into an attractive design that we had never seen before. We all deeply respected Kuramata both in terms of his work and as a person. Japanese design is tight and rational and has no unnecessary elements. But Kuramata’s work was filled with mystery, a world that we are not ordinarily capable of expressing. My work might have been different had I never met him.”

—P.M.

“The recent vogue for electric lamps in the style of the old standing lanterns comes, I think, from a new awareness of the softness and warmth of paper, qualities that, for a time, we had forgotten,” novelist Junichiro Tanizaki noted in his seminal 1933 essay, “In Praise of Shadows.” Tanizaki famously compared the traditional Japanese attitude toward light and shade with modern Westernized ideas in the essay—the differences he noted remain to this day.

IN-EI, a Japanese term that means shadow or nuance in English, is a collection of lighting developed by Miyake in collaboration with Italian manufacturer Artemide. IN-EI’s collapsible forms came out of the explorations for the 132 5 collection, in which Miyake exploited the fact that creased paper has a tendency to spiral when it is folded or unfolded. The material eventually used in the lamps is a nonwoven polyester surface made entirely from recycled PET bottles. However, it still has the warmth and softness that Tanizaki praised in his essay—it is made at a paper mill via the exact same process used to make paper. —A.R.

Miyake and the Miyake Design Studio have always been characterized as experimenters—working either with new materials, natural or synthetic, or else mixing materials and finding ways of making them more supple, shiny, or more textured. “Fabric is like the grain in wood, you can’t go against it,” Miyake told Time magazine in 1986. “You know what I like to do sometimes? I like to close my eyes and let the fabric tell me what to do.”

Miyake believes that you have to learn from fabric every single time you use a new one: “The better you know it, the more you keep learning,” he said. “The weight, the body, the fall of the fabric all determine what it will eventually be made into.” Miyake sees that it is the designer’s job to work with manufacturers to create clothes from materials in such a way that those who wear them have “the freedom of expression and its resulting joy.” —P.M.

As a young boy, Miyake used to pass by the Peace Bridges, which Isamu Noguchi had designed as a memorial to the atom-bomb victims of Hiroshima. The balustrades, also designed by Noguchi, made him realize, “This is design.” He didn’t know whether he was talented enough to reach that standard, but he decided that he would try. “His expression is so simple and amazing,” Miyake explained in an interview. “He was my hero.”

Impressed by Noguchi’s humanistic ideals and his creativity, Miyake sought out his work through books, photographs, and drawings by the artist. When Miyake moved to Paris in 1965 to pursue a career in fashion, one of the few possessions he took along with him was a photo of Noguchi. In 1997, Miyake guest-curated an exhibition, Arizona: Isamu Noguchi and Issey Miyake, which included Noguchi’s sculptures and lamps. The show examined at the intersection of American and Japanese culture, but was also, in part, a tribute to his mentor and close friend. —P.M.

In 1992, Lithuania participated in the Olympic Games for the first time after gaining its independence following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Miyake received a request via Dr. Edward Domanskis, a California plastic surgeon who had become the Lithuanian team’s physician. The team commissioned Miyake to create the design for its official uniform, which consisted of a hooded jacket made with random pleats, T-shirts, silver pants, caps, and shoes. The collar featured the national flag and name and zipped up to form a hood. A patchwork pattern of the Olympic logo and flag and the name of the team’s country was created in a width great enough to account for contraction during pleating.

The basic look was familiar, but just about everything he used was novel: a lightweight polyester fabric cut with a new technique involving hot metal, new oversize zippers, and a new method of pleating the fabric. “I worked hard,” Miyake said. “I was studying the whole time, and we learned so much.” —P.M.

When Miyake started working on Pleats, instead of focusing on how clothes were made he thought about how they were used. He wanted to create garments that would be light and could be easily cared for. It was not just about using new technologies, but making things with obsolete machines or reworking materials. In the late ’80s, Miyake began research on pleating. Inspired by a lightweight polyester-silk scarf folded in four and pleated at an angle, Miyake went on to research a new pleating technique based on modern technology and engineering that would give way to many new forms of clothing. For Miyake, Pleats Please should be seen not as couture nor fashion but as “just clothes.” “After I began to make them, I finally felt I could embrace the word design,” Miyake once wrote. “By sending Pleats Please out into the world, I feel I have finally become a designer.” —P.M.

Early in his career, Miyake often visited Kogei, a craft shop in the Ginza district of Tokyo, where he learned about Japanese traditional techniques and materials. Along with the team from the Miyake Design Studio, he visited small workshops all across Japan to see techniques of weaving and dyeing. He became interested in traditional Japanese fabrics like sashiko, a quilted material in primary colors, stitched in geometric patterns; shijiraori; and oniyoryu. He was also interested in the everyday work clothes that cart drivers and carpenters used to wear, studying them for their beauty and functionality. Miyake once said that it was in May 1968 in Paris, France, when he realized clothing had to appeal to everyone: “As I observed people there, I realized that what I had to make were simple, everyday clothes, like jeans and T-shirts.” —P.M.

“The task of design is to make concepts [into]realities,” Miyake said of his studio’s Reality Lab. “and to actively experiment until products are in the hands of those who will use them.” The lab was established in 2007 with an 11-member team comprising both young experimenters and veteran engineers, working on new ways of making. The lab’s first output, released in 2010, was the 132 5 collection, its numerical name an indication of how the pieces moved through various levels of dimensionality. Alongside the collection, the lab also developed a fully recycled polyester material (which members wear in the photograph above). Reality Lab. went on to collaborate with computer scientist Jun Mitani, who had developed a software program for what he calls 3D origami, creating continuing additions to the 132 5 collection, as well as IN-EI, a 2012 collection of collapsible lighting. —A.R.

Part of the autumn-winter 1980 collection, Plastic Body (above) was the first work in Miyake’s Body series—a five-year effort to leverage various traditional and modern technologies to turn clothing into a sculptural medium. Made of molded fiber-reinforced plastic, Plastic Body is mass-manufacturable, a standardized, reproducible, synthetic skin to be worn over the wearer’s own. In the book Issey Miyake: Bodyworks (Shogakukan, 1983), writer Shozo Tsurumoto conveys the conceptual importance of skin in Miyake’s designs through two photographs of naked female torsos: one of a young woman and the other of an aging one. “The seamless and taut skin surface of the young body contrasts with the wrinkled and textured surface of the aged,” writes Yoshiko Iwamoto Wada. “Skin is portrayed as a two-dimensional plane that records the process of aging, imprinting the creases made by the force of time.” —A.R.

For the Tattoo collection, presented in New York in 1971, Miyake was inspired by traditional Japanese tattoos created in homage to the dead. They are updated here by printing the tattoos, done in memory of music heroes Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin, on jersey cloth. —P.M.

When not worn, Miyake’s Flying Saucer multicolored dress is no more than a pleated disc. When worn, it opens out into a sculptural cocoon around the body. This is due to the technical nature of the permanently pleated polyester fabric and the construction of the garment. The dress returns to its original shape after wearing and washing and is easy to store when collapsed into its accordion-pleated form. The concept pays homage to American sculptor Isamu Noguchi, whom Miyake credits with teaching him everything he knows about space and proportion. Like Noguchi’s Akari light sculptures, Miyake’s tubular dress looks more fragile than it is. —P.M.

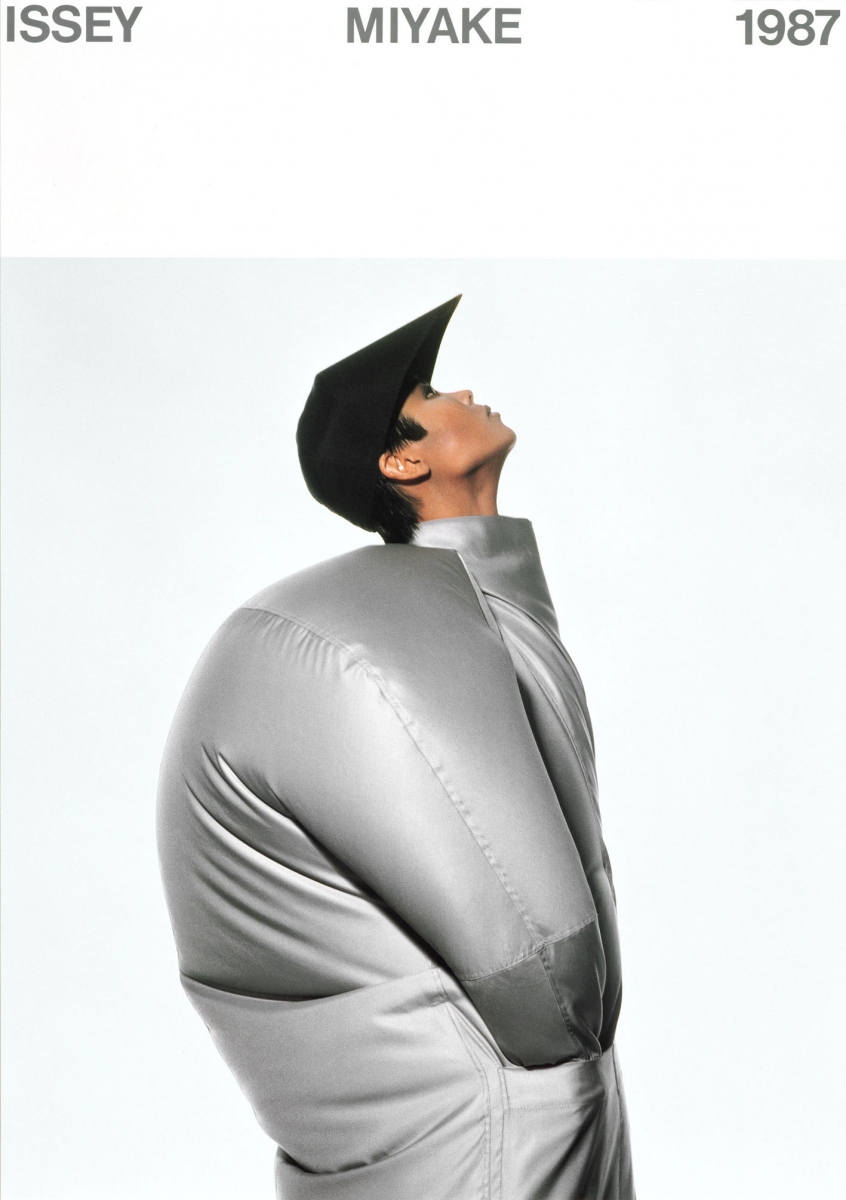

This striking poster for the spring-summer 1987 collection, photographed by Irving Penn and designed by Ikko Tanaka, features two pieces from the 1986 collection, the Balloon Raincoat and Bird’s Beak Cotton Cap. Turning surfaces into volumes is the basic action to which Miyake continually returns—his recent 132 5 collection makes reference to this as well—and Penn emphasized this by exaggerating the volume of the raincoat. —A.R.

Waterfall Body, from the autumn-winter 1984 collection, is a bodice created by partially covering a knit fabric with silicon, draping it on a mannequin, and allowing it to harden in a shape that resembles flowing water. Aquatic inspirations are common in Miyake’s oeuvre—his first fragrance, created in 1992, was named L’Eau d’Issey. The obsession with water, the designer has explained, is a personal one. “You know what I love? Really love?” he once exclaimed. “Warm water and snorkel diving. That’s a dream awake— lying down in the water and watching the fish flash by.”

—A.R.

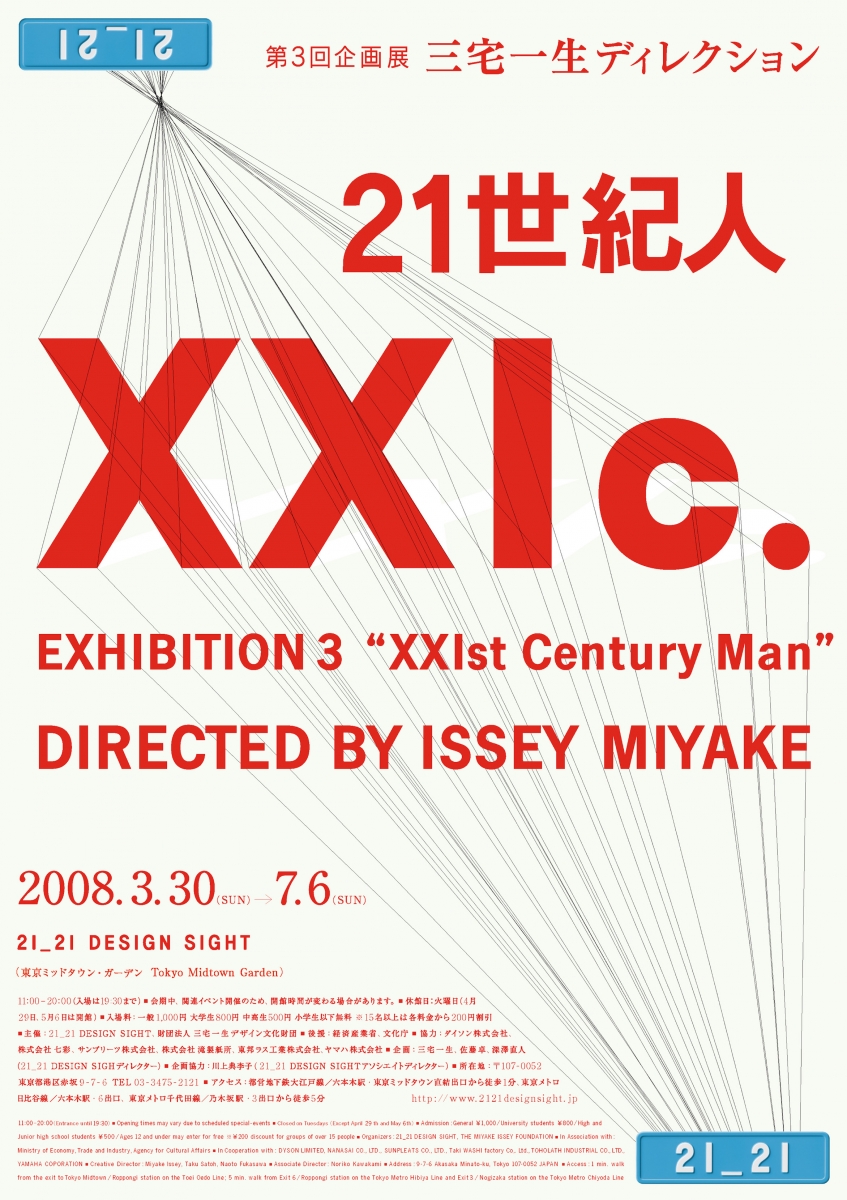

XX1c., a term used in archaeology and museum studies to refer to the 21st century, was the basis for the XXIc.—XXIst Century Man exhibition in 2008 at 21_21 Design Sight in Tokyo, which explored the possibilities of bodies, lives, design, and manufacturing in an age facing serious environmental issues and the depletion of resources. Curated by Issey Miyake, it asked the questions “Where are we headed in this new century?, What are our hopes?,” and “How do we build our future?” Miyake, alongside creative directors Taku Satoh and Naoto Fukasawa, featured the work of 11 architects, designers, and artists, including Isamu Noguchi, Ron Arad, Nendo, Dai Fujiwara + Issey Miyake Creative Room, and Yazou Hokama, plus his own, to explore the environment and new technologies. Nendo, for example, presented a chair made from a wastepaper by-product, and Dai Fujiwara created an installation using Dyson vacuum cleaners. —P.M.

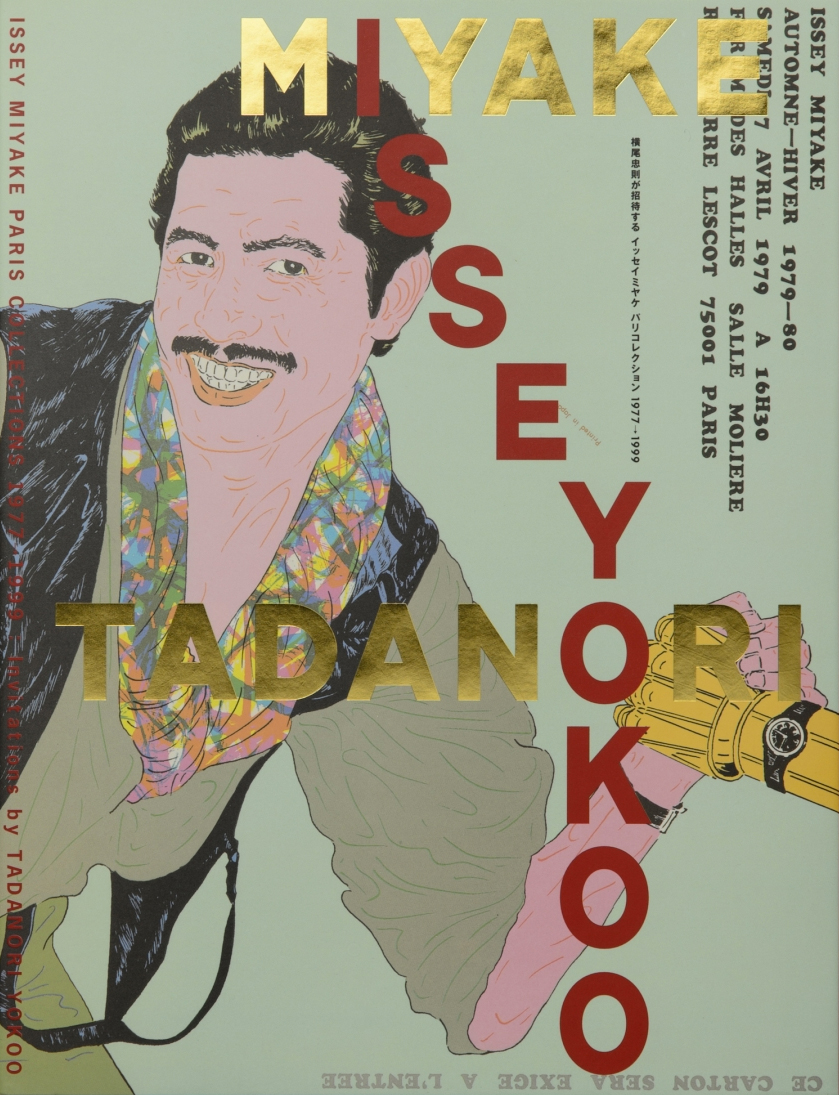

Yokoo is known for bringing influences of Pop and Psychedelia into Japanese art. “I’m quite confident about my influence on different parts of Japanese culture in the 1960s and 1970s,” he declared in a 2015 interview with London’s Tate Modern, listing all the fields he had been involved in, from design to film appearances, and noting of his textile work. “My collaboration with Issey Miyake has been going on for 45 years.” The two innovators met in New York in 1971, at the first international show of Miyake’s work at the Japan Society. Beginning in 1977, Yokoo has designed the invitations for all of Miyake’s Paris shows, in addition to creating prints for various collections. The 2005 exhibition Issey Miyake Paris Collections 1977–1999: Invitations by Tadanori Yokoo (poster shown left) showcased the output of this creative collaboration. —A.R

Miyake has occasionally based his designs on animals such as monkeys, swallows, or starfish. His Zoo A-POC collection from autumn-winter 2001, for example, resembles whimsical animals found nowhere else in the world. Like animal crackers, the group includes a “turtle” design garment, which can be worn with arms and legs emerging from any of the vertical, horizontal, or middle openings. Other animals in the collection include an octopus, a monkey, a teddy bear, and a panther. —P.M.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025