September 6, 2016

The 10 Best Cities to Live In (2016)

Metropolis reveals its 2016 rankings.

Copenhagen: Metropolis‘s top livable city of 2016.

Courtesy Anne Mie Dreves

In establishing our 2016 city rankings, we focused on the concerns at Metropolis’s core—housing, transportation, sustainability, and culture. Working from an initial list of 65 cities nominated by our editors, we conducted in-depth research and comparative analysis according to these criteria, narrowing our list to 25 and eventually 10.

Though our overall judging process took into account many different metrics, from housing rents and commute times to artist subsidies and green space, our local correspondents have chosen to spotlight a few areas in which their cities are doing well, along with the potential challenges that still lie ahead for them.

Copenhagen

Berlin

Helsinki

Singapore

Vienna

Tokyo

Oslo

Melbourne

Toronto

Portland

#1 City to Live In

Copenhagen

Designed by Dissing+Weitling, the Cykelslangen is a 771-foot-long elevated bikeway that snakes past the Fisketorvet Mall and connects a highway to the Bryggebroen, a bridge that spans the harbor. A hit with locals, it has become a vital piece of infrastructure, cutting commute times drastically.

Images Courtesy Anne Mie Dreves

New York and many other city-rankings regulars have been Copenhagen-ized, with smart streets, bike lanes, and small public space projects—not to mention the culinary vogue for ramps and the new Nordic kitchen. But how is Copenhagen itself staying on top of its game?

Bicycle infrastructure is a big priority. For the average Dane, cycling is not a display of athleticism but a part of everyday life. Today almost 45 percent of Copenhagen’s population commutes by bike, a result of efforts on the part of the city to enhance infrastructure through the Bicycle Strategy 2011–2025.

One component of the strategy, which was developed by the city’s traffic department to make Copenhagen “the world’s best bicycle city,” is the Cykelslangen, or Bicycle Snake, completed in 2014. A photogenic orange ramp, it has become a media darling and serves Copenhagen commuters quite well, reducing the commuting time for many by half an hour. Winding its way between some big office and retail blocks at the water’s edge and across a jumble of stairs, the Cykelslangen connects to the Bryggebroen, a bridge dedicated solely to cyclists and pedestrians that spans the Copenhagen harbor. These two pieces of bicycle infrastructure link to a greater network of Cycle Superhighways. “Research shows that Danes are becoming increasingly unhealthy, due to passive modes of transportation,” declared Tine Brandt-Nielsen, project manager of the Cycle Superhighways, at the Danish Folkemødet earlier this year. “At the same time we know that 68 percent of the population in Greater Copenhagen would like greater investments in bicycle infrastructure.” Rolled out in 2012, 26 Cycle Superhighways are now under construction.

In Denmark, legislation mandates public access to the entire coastline. The Cykelslangen can get you to the water, but it’s Copenhagen’s new Harbor Ring that takes you around the city’s waterfront. Inaugurated in May, the Harbor Ring is an 8-mile circuit of pedestrian and bicycle paths encircling Copenhagen’s inner harborscape. It intersects with the Cykelslangen and includes the Bryggebroen; the very poetic Cirkelbroen (Circle Bridge) by world-renowned artist Olafur Eliasson, which emulates the masts and rigging of a sailboat; and the Inner Harbor Bridges, including the so-called Kissing Bridge, which now finally connects—after some technical challenges—Copenhagen’s iconic tourist destination of Nyhavn with the über-trendy Paper Island, the go-to place for street food.

Artist Olafur Eliasson was inspired by the fishing boats of his childhood when he designed the Cirkelbroen bridge. Connecting the Christiansbro neighborhood to Appleby’s Square, the bridge consists of five merged circular platforms, and is part of a larger ring of roads and bridges that allows Copenhageners to bike or walk all around the harbor area.

But perhaps more importantly, the common citizen now has the opportunity to take wonderful strolls around the harbor’s edge, threading through the city’s hot spots; former pockets of tranquility, such as the Library Garden, which is currently under siege by Pokémon Go players; and other charming, lesser-known places best left off the record.

The strolls are also a reminder, if one were needed, of the fact that Copenhagen is a coastal city. While waterfront access is now an uncontested amenity, extreme weather in the form of storms, excessive downpours, and cloudbursts is proving to be an increasing challenge. The most extreme to date was the record-breaking cloudburst that struck Copenhagen on July 2, 2011, wreaking widespread havoc and causing 6 billion Danish kroner (approximately 1.4 billion USD) in damage. The eventful Saturday night prompted a greater awareness of the need for climate action. In 2012, Lord Mayor Frank Jensen and mayor of technical and environmental administration Ayfer Baykal laid out the CPH 2025 Climate Plan, whereby Copenhagen aims to be the world’s first carbon-neutral capital.

An important aspect of the plan is the creation of so-called climate districts, which include new public spaces in the form of parks and plazas that double as swells, basins, and runoffs for large amounts of water. The Sankt Kjelds district in the residential neighborhood of Østerbro is the first such prototype, with more projects in the pipeline. “The climate district projects show how, in one fell swoop, we can create beautiful, green streets and urban spaces,” says Copenhagen’s city architect Tina Saaby, “at the same time creating an effective technical solution to channel rainwater away from our streets and out to the harbor, instead of down into our basements. This is architecture that integrates the technical and the aesthetic in a totally new and very exciting way.”

All three of Copenhagen’s high priorities—enhancing transit infrastructure, improving public amenities, and building urban resilience—come together in two new public spaces in the center of the city. Sankt Annæ Place, once merely a formal green space in a very formal part of town, has been reconfigured as a rainwater swell and wateruptake basin. It keeps up well-ordered appearances while adding much-needed strategies for climate events. Next to it is Ophelia Beach, which served ferries and cruise ships in its previous incarnation as the Kvæsthusbroen Pier and is now a huge public plaza in the inner harbor.

“The Ophelia Beach project embodies a nice combination of architectonic simplicity and robust urban space on Copenhagen’s harbor front,” says Mette Lis Andersen, chairwoman of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design, and Conservation, and former administrative director of Realdania, an early investor in the project. A three-story parking lot extends below the development, which was funded through a public-private partnership.

Ophelia Beach is a very prominent example of how Copenhagen has turned its docklands into accessible, sustainable public amenities—the kinds of spaces people will want to bike to. The concrete urban beach juts out into the water, allowing visitors to look almost directly into the Amalienborg Palace on one side and the opera house on the other. At its very end, it ramps gently down into the harbor, affording Copenhageners the rare urban luxury of getting off their bikes and dipping their feet in the water. —Regitze Marianne Hess

This biking route through the Nørrebroparken is a result of efforts by the Danish capital to promote healthy, sustainable transit.

The area around the Royal Danish Playhouse is the site of Copenhagen’s most recent urban experiment. Bikers can make their way onto the concrete pier, which circles around the Playhouse and onto the water, running past a number of small public spaces.

At the end of the pier is Ophelia Beach, a temporary project that is being converted into a permanent feature by architects Lundgaard & Tranberg. The area has become a popular spot to look out over the harbor or walk down right to the water’s edge.

#2 City to Live In

Berlin

Designed by architect Julian Breinersdorfer, the 107,639-square-foot Factory Berlin houses Twitter Germany, local powerhouse Sound Cloud, and other Berlin-based start-ups.

Courtesy Werner Hutmacher

Berlin, once dubbed the metropolis “condemned forever to becoming and never to being,” is yet again in flux as it absorbs new demographics: nomadic tech start-up workers, young creatives in search of affordable studios, and refugees seeking new lives.

In August 2014, the German government unveiled an ambitious three-year agenda that placed digital growth at its forefront. In Berlin, this has manifested itself in support for start-ups and digital infrastructure, exemplified by a citywide network of 100 public Wi-Fi hot spots— coverage even extends to the Tiergarten and Gleisdreieck parks—which has been partially operational since June.

The city’s architecture is also beginning to reflect these changes, according to Berlin-based architect Julian Breinersdorfer, whose Google-funded Factory Berlin is the mother of all coworking spaces. Tech royalty such as Twitter, SoundCloud, and Uber have set up shop in the converted brewery, where exposed brick walls frame open offices, cafés, lounge areas, and outdoor plazas. “Clients building for the tech industry are more open-minded toward radical ideas than standard real estate developers,” he argues. “The industry’s focus on collaboration and flexibility enabled us to work out a very open plan.”

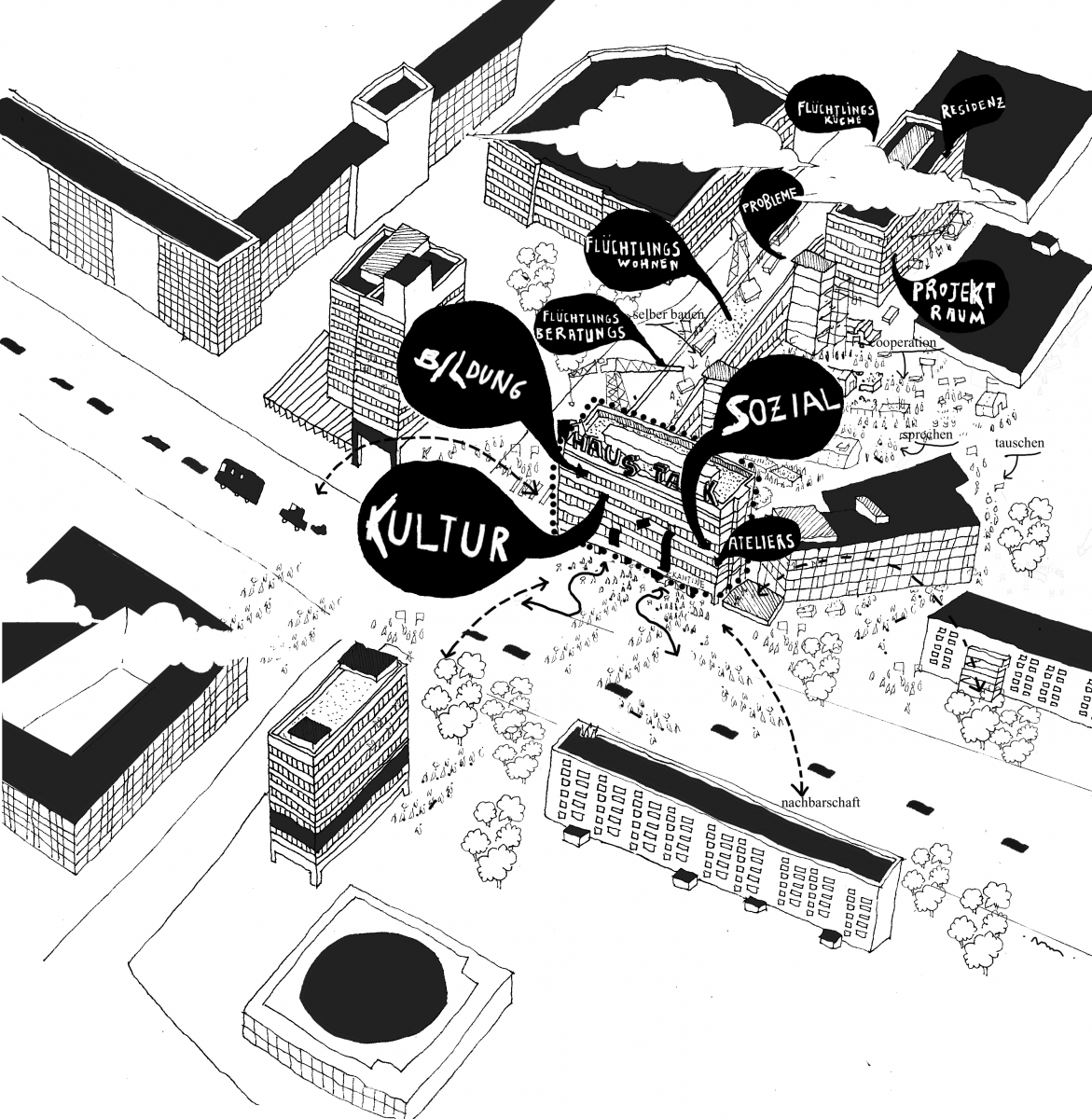

This repurposed, multifunctional architecture is emerging as an important typology beyond Berlin’s tech world, and one key example is the proposed Haus der Statistik—the sociocultural yin to the Google Factory Berlin’s economic yang. Put forward by an independent coalition of artistic and social organizations, the Alliance of Endangered Berlin Studio Buildings (AbBA), it seeks to convert a 430,556-square-foot former GDR-government facility into a housing complex for refugees and creatives, a stone’s throw from Alexanderplatz. Already, the plan has won private funding and support from prominent Berliners, including district mayor Christian Hanke. Markus Bader of raumlabor architects, which has been working on the design, says the project “would be an amazing step forward in the perception of what independent actors can achieve. We have accumulated the knowledge, network, energy, and financial and political support for the project to successfully do this big thing.”

In this way, Haus der Statistik is something of a barometer for Berlin’s future. With the disappearance of an estimated 600 artist studios in the past two years alone, the AbBA initiative is a response to genuine needs within the city’s creative community (not to mention for those seeking asylum). As Bader puts it: “Without being whiny, Berlin is becoming like a normal city. It used to be a special city.”

If recent legislation is anything to go by, there is reason to be optimistic. A new law restricting the rental of whole apartments via Airbnb—the catchily titled Zweckentfremdungsverbot—went into effect in May. Following the imposition of citywide rent controls in June 2015, it is the latest attempt to curb rental costs, which rose 56 percent from 2009 to 2014. Further progress is being made by alternative housing models such as cooperatives and the Baugruppen (cohousing)—residentrun building groups designed to bypass developers—which are creating affordable and autonomous communities outside the for-profit private sector.

It is these initiatives that are most vital in Berlin today. As London’s status as Europe’s cultural capital is called into question following the Brexit referendum, Berlin’s stellar pedigree of arts events such as CTM, transmediale, and the Berlin Biennale is taking on greater significance—and the spaces required to host them are becoming increasingly crucial. If these new developments can cater to and integrate the wide range of newcomers to the German capital, it will resist the stasis and divisions that plague its European counterparts. —George Kafka

A diagram of the Haus der Statistik project emphasizes its social connection to its surroundings.

Courtesy Haus der Statistik

In terms of housing, projects like the Co-op Housing at the Spreefeld in Kreuzberg are being celebrated for their progressive development model.

Courtesy Andrea Kroth

#3 City to Live In

Helsinki

Löyly public sauna, which opened in May, exemplifies a new kind of urban thinking. Designed by Avanto Architects, the project employs eco-friendly wood panels on its exterior.

Images courtesy kuvio.com

Given the presence of Arabia, Artek, and Iittala products in nearly every Finnish home, it isn’t surprising that design has been embraced at the city scale to improve Helsinki. Although relatively small for a capital, Helsinki has long ranked highly for livability thanks to its top-tier education, public transportation, safety, and proximity to nature. But according to its first chief design officer, the newly appointed Anne Stenros, an old Finnish idea is experiencing a resurgence in the city. “Talkoot is a very traditional concept in Finland. It’s the idea that if something has to be done, let’s do it together,” says Stenros. “These ideas from old village life are coming back. Talkoot isn’t about grand gestures, but about humanizing cities on any scale.”

Stenros suspects that talkoot’s reemergence in Helsinki is linked to increased interest in the sharing economy, particularly among the city’s creatives. Free-to-use sewing machines and 3D printers now appear in libraries; locally organized block parties take over in the summer; and Restaurant Day, founded in 2011 to allow anyone to open a food pop-up, is more popular than ever. Larger projects also reflect talkoot in their efforts to humanize the city. Following community-design consultations last year, Vallisaari and Kuninkaansaari, former military islands hitherto off limits to the public, recently opened to considerable acclaim as a public space and nature reserve. Another new amenity, the Löyly public sauna, which combines a sauna with generous public spaces, has its roots in Helsinki’s year as World Design Capital in 2012. “[WDC] showed us that Helsinki was open to new kinds of experiments,” says Stenros. “For me, the top deck at Löyly is the best place in Helsinki right now because it provides a new perspective on the city.”

As 2017 marks the 100th anniversary of Finland’s independence, and forecasts project for Helsinki a dramatic population increase to two million people by 2050, a lot of current construction looks to the future. Near the central railway station, foundations have been poured for a grand public library, set to open in 2018. An extension to the metro network, connecting the city center to Aalto University, will be operational by year-end, and plans are afoot to encourage the end of private car ownership by 2025; Helsinki is nothing if not ambitious. Of course, those ambitions occasionally lead the city to stumble: Its much-lauded on-demand bus service Kutsuplus, launched in 2013, was canceled at the end of last year because of limited funding.

But perhaps the main goal is residential housing. While other capitals struggle with rising housing costs, Helsinki is undertaking large-scale building to contain upward price trends for current and future residents. The city’s stated ambition is to provide a minimum of 6,000 new residential units per year. “There is a big transformation taking place in Helsinki,” says Veera Mustonen, head of Smart Kalasatama, a “smart city” housing development of 2,000 inhabitants northeast of the city center. “One driver is that it’s a very fast-growing city, but another is that the current generation of decision makers, designers, and planners is changing and looking for ways to make the city livelier, and also to give more space to new ideas for better living alongside opportunities for new business development.”

Stenros is eager to encourage such developments. “The city is increasingly emerging as a platform where one can create innovation,” she says. “Young people used to want to work for big Finnish corporations, but a recent survey showed that the city itself is now one of the most desirable employers. That says something very interesting about how people today see Helsinki.” —Crystal Bennes

#4 City to Live In

Singapore

Singapore’s $4.5 million BCA SkyLab is the world’s first rotatable laboratory for the tropics. Inside, the facility is split into two rooms: a reference space and a test cell. These configurable compartments allow for the study of sustainable building technologies like sun-shading, ventilation, and LEDs.

Courtesy Kua Chee Siong/The Straits Times

Singapore, an economic boomtown, ranks prominently on many a list of the world’s richest countries year after year. Yet, for all its abundance, it is still largely a dependent city-state. With scarce land and resources, Singapore imports just about everything—from food and water to energy. Partly because of this, the Lion City is becoming a leading exporter of sustainability solutions.

In 2009, Singapore embarked on an ambitious plan to address many of its constraints. The Sustainable Singapore Blueprint set forth urban policy goals, including water-recycling initiatives to reduce reliance on neighboring Malaysia, where Singapore sources almost half its water supply. It also promoted energy efficiency targets, such as greening 80 percent of the city’s building stock by 2030. With 31 percent of buildings Green Mark certified as of this year, Dr. John Keung, chief executive officer of Singapore’s Building and Construction Authority (BCA), believes they are on target to meet this goal. Unlike the U.S. Green Building Council’s voluntary LEED program, BCA’s Green Mark “requires all new constructions to be built to a certain standard or they won’t be approved for required licenses,” he says. “Existing structures will also have to go forward for certification when they eventually replace things like their cooling systems.” Yearly submission of energy consumption information to the BCA is also mandatory.

Collection of data like this has positioned Singapore as a living laboratory. And through public–private partnerships, the government continues to develop smart-city solutions via innovative projects like the newly opened BCA SkyLab. Launched in collaboration with California’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, this rooftop research facility simulates real-world building conditions and runs energy performance experiments to further improve sustainable design. “We’re a global leader in green buildings in the subtropics,” says Dr. Keung. “The lab will help us to further study how green buildings can be achieved, and then we can share our sustainability knowledge with regional countries.”

Singapore’s open data portal is another data analytics tool the government is banking on to study and test urban solutions. Anyone can log on to the online database and download real-time information on things like electricity consumption, traffic congestion, and education from 70 public agencies. Part of the goal is to inspire citizens to actively seek solutions to improve their own lives. More than 100 apps have been created, including personalized map planners that encourage more public transport use and trackers to reduce cigarette-butt litter, since the web repository became available five years ago. But, with a shortage of STEM talent, the city has cast its net beyond its tiny borders. This year, Smart Nation Fellowship was launched to encourage regional and international scientists, developers, and coders to spend up to six months working alongside the government on tangible solutions to pressing public-sector issues.

So far, it appears Singapore’s many sustainable initiatives are working. Smart-city pilot programs like Punggol Eco-Town have sprung up, car-lite initiatives have reduced Singapore’s carbon footprint, and more than 62 miles of bike paths have been built to encourage alternative modes of transport. “We see vast opportunities to use technologies to improve the way we plan and manage the city,” says Lim Eng Hwee, chief planner and deputy chief executive officer of the Urban Redevelopment Authority. “We believe the efforts in this area are important to build a future city with an even better quality of life, which is ultimately what being a Smart Nation is all about.” —Tamy Cozier-Charles

CapitaGreen, designed by Pritzker Prize–winning architect Toyo Ito, is the new standard for the city’s building stock.

Courtesy CapitaGreen

The building features several environmentally friendly systems, including a red-and-white wind funnel that directs air into the building’s core to cool offices.

#5 City to Live In

Vienna

Courtesy Vienna Biennale

Vienna is designed for equality. Social design plays a huge role in the city’s planning and development—and always has. “That is a long tradition, going back to the Red Vienna period,” says Thomas Geisler, one of the founders of the city’s annual design week, and now the director of the Werkraum Bregenzerwald. “Basically, it is a very socially driven government, as it has always been.”

“Red Vienna” was the nickname of Austria’s capital from 1918 to 1934, when the Social Democrats governed the city for the first time after the collapse of the monarchy. Alleviating the housing shortage and improving the living conditions of the working-class population were the central concerns of urban policy then.

Those concerns, it would seem, have made a comeback thanks to new geopolitical pressures on the city. Current and future creative initiatives in Vienna are focused on pressing social challenges, such as the refugee crisis, high-quality social housing, sustainability, mobility, and smart urban projects for a growing and diverse population—all based, in the social democratic tradition, on open dialogue and collaboration with citizens.

The refugee crisis has been a major focus for designers and architects in the past two years. A case in point is the Austrian contribution to the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale: a socialhousing project to accommodate the influx of asylum seekers in the city. Titled Places for People, the exhibition displays photographs and plans of three ongoing interventions, which adapt vacant buildings to temporarily house people while their asylum claims are processed. It is the result of a collaboration among architecture and design offices Caramel Architekten, EOOS, and the next ENTERprise; nonprofits; and the refugees themselves.

Meanwhile, the largest and most ambitious urban-planning project in Europe, the urban lakeside development aspern, is under way, driven by the city in a joint effort with architects, designers, and citizens. Together they are developing a model for the smart city of the future, encompassing technological infrastructure while also promoting a new urban-planning system called Baugruppen housing initiatives. Five such collective projects are already being designed and built by different groups of people, taking their individual lifestyles into consideration.

One initiative, a project called Que[e] rbau, focuses on the LGBTQ community. Its ideal living space has an openness toward queer lifestyles and alternative family forms, the ability to plan apartments individually, a focus on common spaces in the building, and a large garden.

Throughout aspern, great importance is attached to gender equality, along with sustainability, green spaces, and mobility. Even the streets in this futuristic smart city will mostly be named after remarkable women in history—the district council has approved an all-female list for one part of the development, and citizens are engaged in the process of selecting more names.

The concern with gender runs across every scale of design in Vienna, Geisler says: “We just take it for granted. There is a strong contribution from female architects and urbanists planning the city.”

If Vienna can hold on to these enlightened ideals through the refugee crisis, extending the same courtesies to its new citizens that it has to other communities throughout its history, it will remain one of the world’s best cities to live in. —Aline Lara Rezende

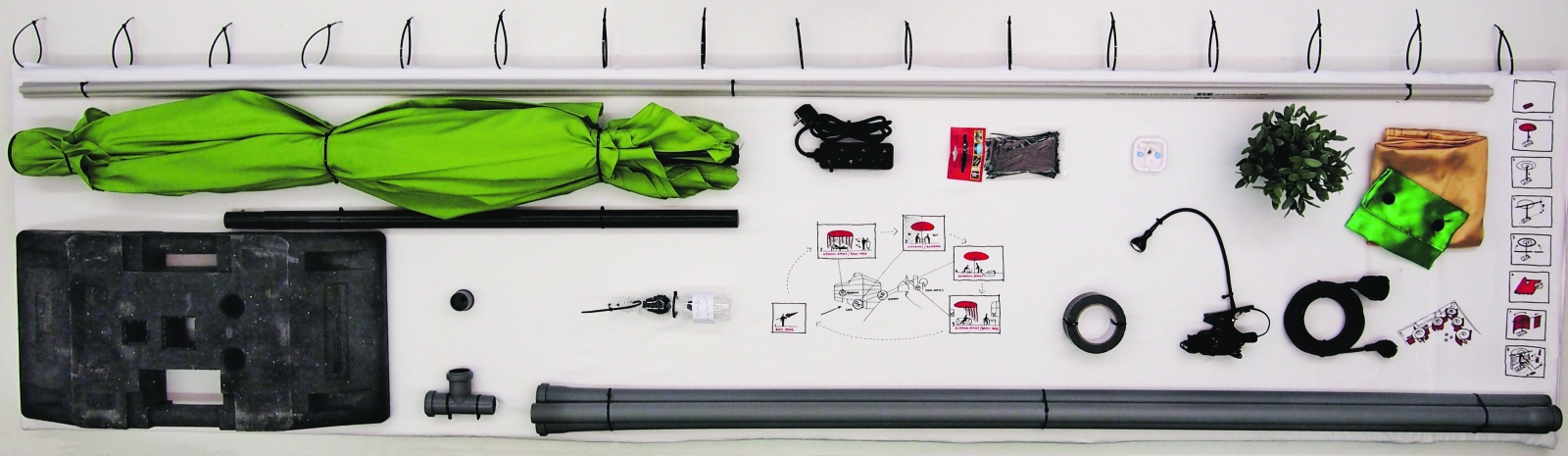

To give 820 residents some privacy in a refugee shelter set up in a 1970s office building, Caramel Architekten developed Home Made, a simple low-cost kit of a parasol, textile panels, and cable ties. Similar elements were later used for the communal areas of the shelter.

Courtesy Paul Kranzier

A digital projection during Elma R, the Vienna Media Art Festival, held in aspern in October 2015.

Courtesy Elisabeth Stöckl

#6 City to Live In

Tokyo

In an attempt to tackle Tokyo’s problem of a lack of burial space, Rurikoin Byakurengedo, a Buddhist temple, opened in neon-lit Shinjuku in 2014.

Images courtesy Yoshio Shiratori

Tokyo: The statistics are as dizzying as its cloud-brushing towers. The Japanese city is home to 13 million residents, 40 million daily commuters, 139 skyscrapers, 216 Michelin-starred restaurants—and an evershifting skyline that changes with high-speed regularity.

The city has long been known as one of the largest and most densely packed on the planet, with an urban patchwork of distinctive neighborhoods, from teen fashion mecca Harajuku and the upmarket Ginza to electronics hub Akihabara. It also excels at mixing the futuristic with the traditional, as Kengo Kuma, the architect behind the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Stadium, explains: “What makes it unique is the clear contrast of townscape in Tokyo, where narrow passages among old wooden houses still exist along with big roads and buildings constructed in the 20th century.”

Not to forget how well it works. Despite its vastness, crime rates are low, the streets are clean, the trains are punctual, and the atmosphere is often surprisingly calm. In contrast to many Western cities, its architecture is also defined by a sense of disposability, a culturally ingrained legacy of Japan’s exposure to natural disasters and wartime destruction.

“Traditionally buildings are not seen as permanent structures in Japan,” says Mark Dytham, of Tokyo-based Klein Dytham Architecture. “In the past, all buildings were made of wood and tended to burn down, rot, or be destroyed by typhoons or earthquakes—as opposed to in the West, where buildings are made of brick or stone and are built for 400 years.”

On a less positive note, the city often feels more like jigsaw puzzle sprawl than a premeditated urban blueprint, with its disposable skyline resulting in an at-times jarring lack of architectural or aesthetic consistency among buildings (picture a neon-lit 7-Eleven, an old wooden shrine, a glass skyscraper, and a dated 1980s apartment block sitting in a row). Navigating the public transport network can also be a daunting task for those not familiar with the city.

And then there is the issue of overhead cables: Despite Tokyo’s reputation for being futuristic and progressive, a quick skyward glance reveals how the vast majority of the city’s power cables still lie in messy tangles above the streets, with critics regularly condemning them as unsightly.

Demographics are also a concern. Its rapidly aging population and declining birthrate are growing issues for politicians and architects alike. Sugamo—a neighborhood often dubbed Harajuku for old ladies—provides an innovative urban template for a “silver” population, from the widened wheelchair-friendly pavements to the green man flashing for longer periods at traffic lights.

There is a countdown under way, however, for an upcoming event that Tokyoites hope will give the city a major boost—the 2020 Olympics. A raft of major regeneration projects, shiny new developments, hotels, and infrastructure upgrades (including plans to move at least some of those overhead power cables underground) are in the works. New constructions include the Shinbashi No. 29 Mori Building, a 15-story multiuse retail and office space in Shinbashi, a prime redevelopment area for the Olympics. This project, to be completed in 2018, will be linked via the newly upgraded street Shintora-Dori—dubbed Tokyo’s Champs-Élysées—to the Olympic Village and Stadium.

So how will Tokyo look in 2020? According to Kuma, there will be a shift from “a city of highways and shinkansens,” as was the case during the high-economic growth era of the 1964 Games, toward something more grounded: “a humanfriendly, walkable town.” —Danielle Demetriou

The architecture, by Kiyoshi Sey Takeyama of Amorphe, is clean-lined, minimal, and unabashedly contemporary with a futuristic edge—complete with high-tech basement vaults able to accommodate the cremated remains of 7,000.

#7 City to Live In

Oslo

Built on piles in the Oslofjord, the Oslo Opera House appears to rise from the water and create a visual connection between downtown and the Bjørvika harbor. It functions partly as workspace for 600 members of the National Opera and Ballet and a public space for more than a million visitors each year. Both the building’s lobby and sloped roof (which can be reached from the outside) are accessible to the public 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Courtesy Nancy Bundt

Location has always been an important asset for Oslo. Characterized by hillsides and forests, its natural landscape has made it a popular destination for nature-seeking tourists. But new and modern architectural projects like the Astrup Fearnley Museum by Renzo Piano and Snøhetta’s glacierlike Opera House have also positioned Norway’s capital city as a cultural cityscape.

Oslo’s shifting urban policies have spurred the design of several cultural landmarks by world-renowned architects. Part of this involved transforming its waterfront over the past decade and a half in an attempt to attract multinational companies and the creative class. By 2020, the city’s seaside will be an entirely new urban space.

Bjørvika, the old port area where the water meets the city, began developing in 2005, giving Oslo its very own Manhattanesque skyline. Dubbed the Barcode Project and slated for completion later this year, the 2.4-million-squarefoot mixed-use development boasts a number of new high-rise buildings by both Norwegian and international prize-winning architects.

The Oslo Public Library and the new Edvard Munch Museum are two other big projects that will alter the Bjørvika area. The library, by Lund Hagem Architects and Atelier Oslo, will consist of five floors with a full-height atrium at its core, while the Munch Museum—called the Lambda— will house 28,000 items and works donated by the famed Norwegian painter. Together, they represent the city’s focus on creating new cultural experiences for its 600,000 inhabitants. But like most large-scale projects, they are not without their detractors.

The Lambda, designed and currently under construction by Spanish firm estudio Herreros, has been embroiled in controversy since it was approved by Oslo’s city council in 2008. Critics argue the building’s tall and domineering stature, characterized by a large rectangular volume with a tilt on the top, starkly contrasts with Bjørvika’s natural landscape. The 12-story museum, located a few feet away from the Opera House, will likely be a looming presence over the Oslofjord when it’s completed in 2019.

Following the shoreline west from Bjørvika, the construction site for the new National Museum emerges. Designed by Kleihues + Schuwerk Gesellschaft von Architekten, the project will be among the largest of its kind in Europe. The museum’s new building will double its current exhibition space and feature handpicked artworks from Norwegian billionaire Stein Erik Hagen’s $120 million collection. Topped by an illuminated hall of transparent walls, it will be a glowing landmark of lights along the waterfront when it opens in 2020.

A majority of the city’s new cultural buildings under construction will be eco-lighthouse certified—in accordance with a national scheme that certifies projects that meet eco-friendly criteria such as energy efficiency and reduced carbon emissions. Over the next three years, Oslo’s city center will be completely car-free, making it the first European capital to permanently ban automobiles. The city government plans to divest pension funds from fossil fuels, while also devoting $923 million to “super cycleways” throughout the country’s 10 largest cities. These initiatives all play into Norway’s goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2050.

The new blend of urbanism and nature will make Oslo even more appealing to creatives. Coupled with the city’s remarkable growth in its standard of living over the past few decades, Oslo’s new urban expansion is further reshaping its image as a modern city. —Dorthe Smeby

Courtesy Mariannera/Flickr

In 1944, artist Edvard Munch bequeathed a large portion of his work, including thousands of prints, sketches, and manuscripts, to the city of Oslo on his death. Described as “looking more like a postwar municipal building than an art gallery” by the Wall Street Journal, the collection’s current home is severely outdated and in a state of disrepair. The new $314 million museum is expected to attract up to half a million visitors each year.

Courtesy Munch Museum

#8 City to Live In

Melbourne

Courtesy David Hannah Photography/City of Melbourne

Each year when the livability rankings of global cities are released and Melbourne has once again nabbed the top spot— Melburnians smugly sip their cold-brew coffees and chalk up another win over their nearest rival, Sydney. But in many ways that’s a false indicator of the challenges Melbourne faces, and ignores the many ways the city’s leaders and residents are beginning to tackle them.

Public transport—including Australia’s most extensive tram network—is a strong point, and the Victorian state government continues to invest heavily in new projects such as the Melbourne Metro train system, better connecting the city north to south. Still regarded as the country’s cultural heart and creative capital, the city emphasizes events, theater, music, laneways, public art, design, and major festivals such as White Night and Open House Melbourne (OHM)—where hidden urban spaces and public buildings are opened for one weekend a year. These initiatives attract millions of local and international visitors to the central business district and its surrounds annually.

However, livability rankings often exclude cost of living, and say little about the city’s ability to deal with the projected doubling of its population to eight million people by 2050. Emma Telfer, creative director of OHM, believes residents are actively engaged in tackling these problems: “In the last few years we’ve seen a real increase in general public engagement with ideas around city development and urban-planning initiatives. Melburnians really engage with the way the city is developing.”

Since late July, OHM has presented Occupied, an exhibition looking at ways to house a booming population, at the RMIT Design Hub. Exhibition cocurator David Neustein hopes that the show will engage a diverse public audience. “We’d like to raise awareness of both the challenges of the near future and the capacity of architects and designers to respond. Like all Western cities, Melbourne is locked in mortal conflict between private and public interests. But the city has a vibrant and enduring culture of activism, debate, and public inquiry.”

Demonstrating support for this type of public engagement, Melbourne’s lord mayor, Robert Doyle, says that it’s the role of the city council to help inform residents. “Empowering citizens to participate is not only the smart thing to do—it’s the right thing to do,” he says. Melbourne’s community engagement programs include everything from the dissemination of information about planning and urban development decisions, to citizen juries and participatory democracy. “Every tool in the engagement process needs to be communicated exactly to the community,” he explains. “People need to know what their role in the consultation and engagement is.”

A group of Melbourne architects is taking community engagement to the next level. The Nightingale Housing model is a multiresidential concept that focuses on social, economic, and environmental sustainability and strives to involve the community of purchasers (i.e., eventual residents) in its decision making right from the start. Breathe Architecture’s Jeremy McLeod, chair of Nightingale Housing, believes housing has become a commodity, and that initiatives like Nightingale are needed to create sustainable, design-led, and community-focused approaches to housing affordability and livability.

Melbourne is undoubtedly a livable city, with a vibrant food and creative culture, supported by strong infrastructure and a politically and socially active population. But the real challenges facing the city, including population growth and shifting demographics, are testing its residents as well as its political and design leaders. Consulting and genuinely engaging Melburnians will no doubt make the discussion richer, and hopefully result in a better place to live. —Ben Morgan

The city’s laneways are an iconic part of its streetscape.

Courtesy David Hannah Photography/City of Melbourne

The Nightingale Housing project will present a new model for housing in Melbourne.

Courtesy Breathe Architecture

#9 City to Live In

Toronto

With its smart scale and links to the street, the recently opened Ryerson Student Learning Centre signals a shift toward more adventurous architecture in Toronto.

Courtesy Lorne Bridgman

Last fall, Toronto philanthropists Judy and Wilmont Matthews donated C$25 million to build a linear park in an inhospitable place: underneath the crumbling elevated expressway that slices through the city’s waterfront. Toronto’s “Under Gardiner” project arrives during a period marked by a difficult transition from car-centric planning to pedestrian-focused design, says Toronto’s chief planner Jennifer Keesmaat. “We are coming of age as a city right now. We are at a moment when we understand the importance of creating a walkable city.”

In recent years, Toronto has been consistently ranked as one of the world’s most livable and diverse cities. Half of all Toronto residents were born outside Canada, and the region attracts 100,000 new residents each year, including many creatives and millennials drawn to the city’s arts, education, and high-tech sectors. This rapid growth, along with anti-sprawl planning and a robust regional economy, has triggered a record-breaking downtown development boom that has spurred demand for new public spaces and more livable communities.

“It’s a new way of thinking about public space beyond these polite green landscapes,” says Donald Schmitt, a principal at Diamond Schmitt Architects, which developed the Evergreen Brick Works, a former brick quarry that now functions as a wetland and heritage education site.

The city wants the design of major new buildings to reflect the porousness required in a pedestrian-oriented city. Keesmaat cites the new Snøhetta-designed student learning center at Ryerson University, which features generous seating areas that link to the street: “The design of that building is about lingering [and] recognizing that public life takes place on our streets.”

Population and densification are also informing Toronto’s approach to transit and street design. While the city’s subway network is relatively sparse, Toronto is building new light-rail transit lines, adding to its cycling infrastructure, and, in a few cases, closing or narrowing streets, as Janette Sadik-Khan did in New York during her high-profile stint as transportation commissioner.

The city and the provincial government have also made sizable investments in Union Station, the central transportation hub—recently renovated by Zeidler Partnership Architects—and last year launched an airport rail shuttle. While the Union Station upgrades were needed to handle growing commuter volumes, the air rail link has been slow to attract riders.

Meanwhile, Waterfront Toronto (WT), a publicly owned agency, is redeveloping hundreds of acres of derelict waterfront land near downtown with projects by Diamond Schmitt, KPMB, and Moshe Safdie. One recently completed waterfront space is Corktown Common, a 16-acre Michael Van Valkenburgh– designed park that anchors a 6,000-unit midrise community. WT’s vice president of planning and design Chris Glaisek says the design leverages topography, natural materials, and compelling vistas: “It creates a variety of experiences and scales, and a bit of a sense of mystery.”

With growth in financial services, mining finance, and tech, the downtown is seeing new office construction and the redevelopment of early-20th-century warehouses, plus a combination of the two, as with Entertainment One Canada’s new headquarters in QRC West, a tower by Sweeny & Co. built on stilts over an old factory. Planners have also pushed condo builders to make their high-rises more street friendly and less monolithic in their massing compared with older slab highrises. A design panel process introduced in recent years ensures that many projects are peer reviewed for architectural quality. Kyle Rae, a former downtown councillor, cites as one of them FIVE at 5 St. Joseph, a 48-story tower by Hariri Pontarini that looms over restored 19th-century mercantile buildings. As he says of Toronto’s architectural revival, “There’s been an enormous transformation in the expectations of the city and residents.” —John Lorinc

Courtesy Lorne Bridgman

Designed by West 8 + DTAH, the Wavedecks are a series of undulating bridges that span Toronto’s revitalized waterfront.

Courtesy Waterfront Toronto

#10 City to Live In

Portland

Nicknamed the Bridge of the People, the Tilikum Crossing—which is for public-transit, pedestrian, and cyclist use only—is about 1,720 feet long, with around 3.5 miles of cable.

Courtesy Wikipedia Creative Commons

Unlike many cities in the American West, Portland, Oregon, didn’t start out as a boomtown. It’s grown steadily since being founded in the 1850s, endowed with a fortuitous natural location and good access to valuable resources (timber first and foremost). Portland has been booming lately, however, and rather than trees it’s wafered silicon and woven nylon that are fueling growth.

“For a long time, Portland was just Nike and Intel and Wieden+Kennedy— they’re the big rocks in the jar, so to speak,” says Jeremy Webber, director of client strategy at Swift, a Portland digital agency. “It turns out that there was a lot of room in between those big rocks, and nimble new smaller companies are growing like crazy in the empty space.”

So it’s “Stumptown” no more: Try the “Silicon Valley of Sneakers” or the “Silicon Forest” instead. Portland’s craft-mecca reputation notwithstanding, every brewer, baker, and candlestick maker in town could likely work comfortably inside just one of Intel’s billion-dollar computer-chip-assembly clean rooms, and new digital concerns like Swift are popping up all over the city. In addition, Under Armour recently announced it would be joining Nike and Adidas in town, moving thousands of creative staffers downtown later this year. Portland’s got jobs, it’s got a great location, and people are moving in.

By some estimates, more people moved to Portland than to any other American city during the past two years, and there’s record-breaking new construction under way in response. The Pearl neighborhood, reclaimed from blighted light-industrial brownfields beginning in the early 2000s, recently marked the completion of the tallest residential building in the city, BORA Architects’ Cosmopolitan on the Park. Across the Willamette River, Skylab Architecture’s soon-to-open Yard is a significant beachhead in Portland’s previously sleepy industrial inner southeast—what’s happening there looks akin to the changes Williamsburg, Brooklyn, underwent from 2005 to 2015. The Williams-Vancouver corridor in northeast Portland has also been thoroughly transformed in just the past few years.

The population influx is driving some interesting transportation initiatives. For example, there’s the Tilikum Crossing, which is the first major American bridge built without access for passenger cars in decades. It carries Portland’s newest light-rail line into downtown from Milwaukie, 7.3 miles away. This summer, the city at long last debuted an urban cycle-share system, Biketown. Sponsored by Nike, and sporting the company’s signature fluorescent orange, the shaftdriven, Detroit-assembled bicycles may (for a $5 fee) be locked to any of the thousands of existing public stanchions around the city—or, for $20, anywhere. The bikes themselves are tracked by an app, like Car2Go vehicles (which Portland has also embraced). These may sound like small measures, but they represent a lot of learning from other, less successful municipal bike-share systems. Portland is already America’s leading city for bicycle commuting, with around 7 percent of the population pedaling to work. “Our goal is to get 25 percent of all trips in Portland to be bike trips by 2035,” says Dylan Rivera, spokesman for the Portland Bureau of Transportation, “so Biketown is a really important tool.”

It’s not for nothing that Portland finds itself enjoying a late-in-life growth spurt. More than a century of unusual, careful planning decisions is adding up, from the short blocks that encourage Portland’s vibrant, small-business thronged inner neighborhoods to the urban growth boundary that makes it a real metropolis just 30 minutes’ drive from one of the greatest unspoiled scenic areas in the country, the Columbia River Gorge. So, although Portland’s cost of living may be rising too fast for it to remain “the city where young people go to retire,” as it has been called, it is still a city on the rise. —Derrick Mead

The Yard development, above, by Skylab Architecture, is on track to gain LEED Silver certification.

Courtesy Yard

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025