April 14, 2016

The Copyright Law That Should Have Architects Up in Arms

Sweden’s Supreme Court has ruled against Wikimedia in a landmark case over “Freedom of Panorama.” Here’s why we all should be concerned.

Mies van der Rohe’s Chicago Federal Center, including the “Flamingo” sculpture by Alexander Calder

Courtesy Samuel Ludwig

This article originally appeared on ArchDaily.

Earlier this week, the Supreme Court of Sweden ruled against Wikimedia Sverige in a landmark case over “Freedom of Panorama,” a ruling which The Wikimedia Foundation has “respectfully disagreed with” in a blog post. The Swedish Supreme Court’s ruling, in short, states that Wikimedia Sverige is not entitled to host photographs of copyrighted works of art on its website Offentligkonst.se, which provides maps, descriptions and images of artworks placed in public spaces in Sweden.

The concept of freedom of panorama describes a provision in copyright law which extends the right to take and to disseminate photographs of copyrighted works provided those photographs were taken in public spaces. Most people who own a camera (in other words, most people) have probably given very little thought to their freedom of panorama, or any restrictions that may have been placed upon it. But the reality of this little-known copyright-related oddity is something that many people, and architects especially, should find very concerning indeed.

Santiago Calatrava’s Turning Torso in Sweden

Courtesy Flickr user Mirko Junge licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Of course, the central absurdity of restrictions to freedom of panorama is that a photograph of a building or artwork is not the same as a copy of the thing itself. This statement is in no way new or controversial: it was famously the subject of René Magritte’s 1929 painting The Treachery of Images, which featured a painting of a pipe and the statement “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (“This is not a pipe”). So why, then, does copyright law struggle so much with a concept that has been part of the public consciousness for almost 90 years?

The answer to that question lies in the term “derivative works.” Copyright law protects the rights of property owners to make money and otherwise protect the reputation of their intellectual property, and limits the rights of others to associate their own property with it. That’s why the Port Authority of New York was able to make a serious case, in 2014, that dinnerware being sold by a New York store featuring images of the World Trade Center twin towers was harmful to the Port Authority’s reputation. But even that case was widely ridiculed with some asking why the Port Authority was “claiming to own the New York skyline,” and photography is surely an even more minor offense against copyright than a stylized depiction of an iconic work. In the words of the Wikimedia Foundation, “An artist that chooses to permanently place their work in a public place grants the public the right to view the work, whether in person, on a postcard, or on an informational website.”

But even putting that absurdity aside, perhaps the most shocking thing about restrictions to freedom of panorama is the overwhelming complexity of our current situation. Copyright law is by itself wildly complicated, but at least it is controlled by a wide range of international agreements—most notably the Berne Treaty, which at least attempts to give some level of consistency between nations. But there is no such treaty controlling the provision of freedom of panorama, leading to the following situation:

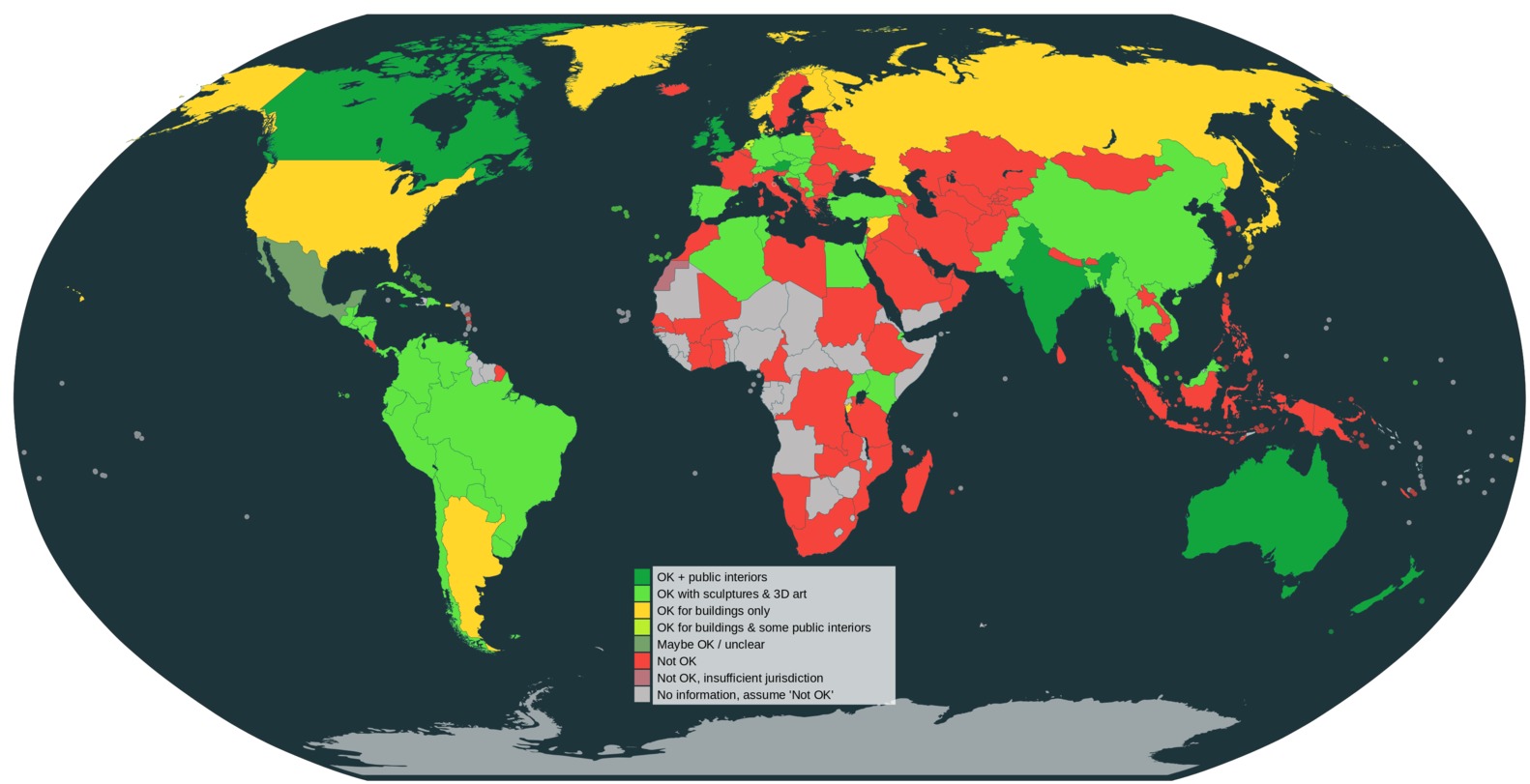

Courtesy Wikimedia users Mardus, Canuckguy and Julian Herzog licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

In the above map, dark green countries have total freedom of panorama for public buildings, artworks and interiors; light green indicates freedom over buildings and artworks but not interiors; yellow indicates freedom of panorama for buildings but not artworks; red indicates no freedom of panorama at all; and the other colors indicate various levels of “nobody knows.”

Let’s apply all that to a realistic situation: imagine that a person from the UK—with some of the most permissive freedom of panorama laws in the world—visits Sweden and takes a photograph of a building and an adjacent work of public art. The recent ruling by the Swedish Supreme Court makes a distinction between taking a photograph (permitted) and publishing it (not permitted), so as yet this person has not done anything wrong. But then she returns to the UK and uploads her photograph to her Flickr account, a website hosted in the United States. As she would like her photograph to be more widely seen she uploads it under a Creative Commons license, allowing others around the world to use it too. Then perhaps an Australian architecture website sees the photo and, using the Creative Commons license, republishes it on their website.

Dubai Skyline, including at its center the Burj Khalifa by SOM.

Courtesy Naufal MQ via Shutterstock.com

The photograph is now widely published and the copyright holders for the building and artwork themselves want to seek damages. But who do they prosecute? Does uploading an image to a personal account on an image hosting site constitute publication? If so, who is deemed to have published it—the user or Flickr themselves? And if Flickr doesn’t constitute publication, is the architecture website in Australia liable for republishing it?

And once a defendant is identified, where should they be prosecuted? In Sweden, where the photograph was taken, and the defendant is likely to lose the case? Perhaps in the UK, where the upload took place, and where the defendant is almost guaranteed to win? What about the US, where the file is actually hosted and where the photograph of the building is fine, but the public artwork is not? Or Australia, where the final, definitive publication took place, but where like the UK, there is almost total freedom of panorama? Those unfamiliar with copyright law might think there is surely an easy answer to this but, as with many international copyright disputes, the answer is “it depends.” The prosecutors would probably attempt to have the case heard in Sweden, while the defendants (whoever they may be) would probably try to have it heard in either the UK or Australia.

In the 21st century, navigating such a minefield of legal issues every time you point a camera outdoors is not only an unrealistic but an absurd proposal. Most people who take photographs have probably never even heard of freedom of panorama—it simply wouldn’t occur to most people that their right to take photographs in public spaces could be restricted. Yet that right continues to be restricted: not only in Sweden last week, but also through a proposal in the EU Parliament last year, where a motion to restrict freedom of panorama across the whole of Europe was only narrowly avoided.

We live in a world where the difference between a building and a work of art is becoming increasingly blurred. We live in a world where it is increasingly unclear what constitutes “publishing” an image, thanks to websites that rely on user-generated content like Facebook, Flickr and Instagram. We live in a world where the division between public and private space is increasingly difficult to determine, as private spaces are monetized and treated like public spaces. We live in a world where images are published and shared across borders, regardless of the obtuseness of local copyright laws in those respective countries.

But most importantly for architects, we live in a world where images of our built environment—shared freely between people via the internet—are increasingly important in constructing a discourse around that built environment. We live in a world that requires freedom of panorama in order for architects to make the world a better place. And architects should be pretty upset about how many restrictions have been placed, and continue to be placed, on that freedom.

ArchDaily editor’s note: In order to make a point about the absurdity of the situation, the three photographs included in this article are—to the best of our knowledge and understanding—in violation of the Freedom of Panorama laws in whichever country they were taken in.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025