July 28, 2014

The Dizzying Heights of Hong Kong’s Hyperdense Cityscape

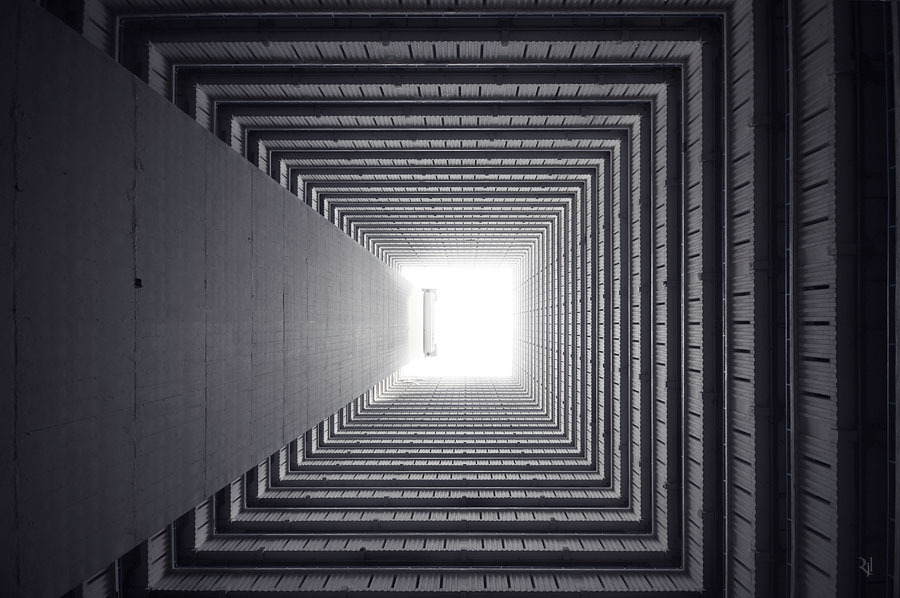

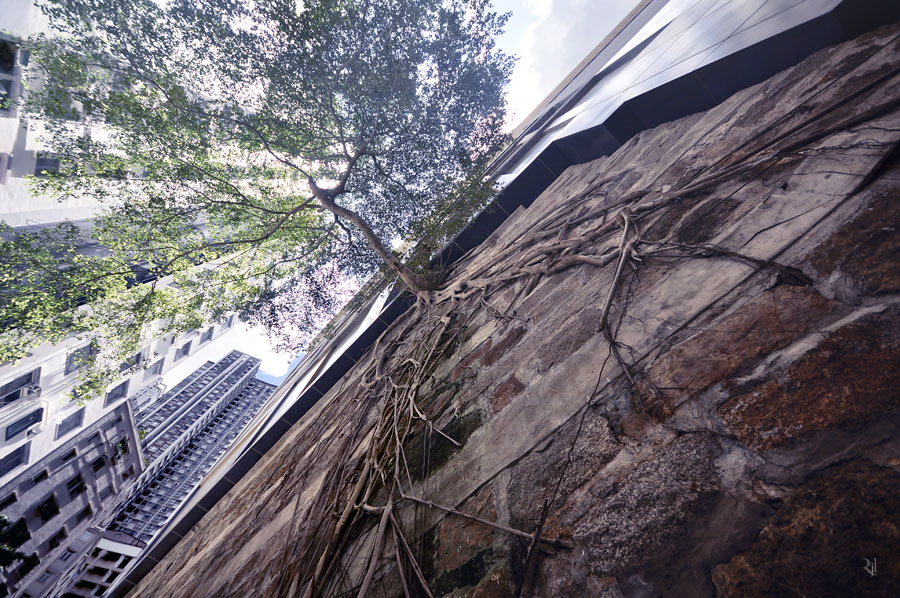

An excerpt from the photographic book, “Vertical Horizon,” pays tribute to the city’s unique and often claustrophobic skyline.

The following excerpt is taken from the book Vertical Horizon, a visual journey through Hong Kong’s urban fabric. The photographs, by Romain Jacquet-Lagrèze, are accompanied by passages of text by Holly Chan & Christopher Dewolf.

If music is the space between notes and the city is the space between buildings, Hong Kong is the space between peaks and valleys—a settlement whose built environment mimics the precipitous topography on which it sits. Whether in a street market or in a country park, skies in Hong Kong are never vast. Nor is the ground reliably present, sloping this way and that, flat only in those areas where it has been artificially reclaimed from the sea.

The result is a city that can never be experienced the way Beaudelaire experienced Paris; walking the streets of Hong Kong is not enough to understand it. This is a vertical metropolis that is lived on multiple planes and in multiple dimensions; there is always something lurking overhead, up a hill, around the corner and down an escalator. The reasons for this might seem evident enough: big city, small space—density is inevitable. But Hong Kong’s particular brand of verticality can in many ways be attributed to a series of historical accidents.

The first was the crush of migration in the decades following 1949, when hundreds of thousands of people fled political, economic and social instability in China. They arrived in Hong Kong only to find themselves in a state of flux, living in wooden shantytowns on the city’s hillsides and in overcrowded tenements. This led to a vast government effort to resettle migrants in public housing, which usually took the form of functional modern tower blocks, many of them identical and distinguished only by giant numbers painted on their facade.

In the private sector, meanwhile, the population boom was accommodated by enormous composite buildings that combined flats, small factories, and other businesses. Building codes were enforced with only the lightest of touches, leading residents to customize their spaces by adding windowboxes, sheet metal awnings, balconies, and racks for drying clothes.

Around the same time, in a much more upscale corner of town, the owners of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel built a footbridge to take guests directly into the Prince’s Building shopping centre across the street. This inadvertently sparked a revolution in Hong Kong’s urban form, as pedestrian space was untethered from the ground level; in the words of architect Jonathan Solomon, Hong Kong has entered a “condition of groundlessness,” when public activity is spread vertically as well as horizontally: there are public parks on shopping mall rooftops, buildings with multiple main entrances and ground floors. You’re as likely to find a restaurant on the 10th floor of a building as at street level. Walking through Hong Kong requires a constant change of grade and elevation, from ground level to footbridge to tunnel.

The best visual representations of Hong Kong come from those who understand its essential verticality. In the 1950s and ‘60s, photographer Ho Fan masterfully depicted this urban palimpsest by capturing the city’s filtered light, staircases and imposing shop signs. More recently, Benny Lam’s series of overhead photos of people living in subdivided flats evoked the makeshift living environments familiar to so many Hong Kongers, whose tiny apartments force them to stack themselves on bunk beds and pile their possessions on towering shelves. And of course, there is Michael Wolf, the German-born photographer who has achieved international recognition for his series Architecture of Density: dispassionate images of Hong Kong apartment towers, cropped so as to give the impression that they are endless.

These photos have always rubbed me the wrong way; they present Hong Kong as a machine rather than a city. By contrast, Romain Jacquet-Lagrèze deals with the same city blocks in a much more optimistic manner. It isn’t just that he has angled his lens like that of a curious wanderer, always looking up or down, marvelling at the bizarre geometric formations of the cityscape. It’s that his photos are essentially humanistic, despite their virtual absence of human figures. People might be invisible in most of Vertical Horizon’s photos, but their presence is always felt, in bamboo scaffolding, hanging laundry, potted plants—all the ephemera of everyday life. This is the vertical city not as a specimen but as a living, breathing, dynamic organism.

This post originally appeared on ArchDaily under the title, Capturing Hong Kong’s Dizzying Vertical Density.

Recent Viewpoints

Viewpoints

Sustainability News Updates for Q2 2025